Poor ol’ Michael Douglas. The 68-year-old Hollywood actor, famous for blockbuster movie roles in which he portrays average Joes who get suckered into having dangerous sex with horny, evil women, recently stimulated the press with some delicious lip service.

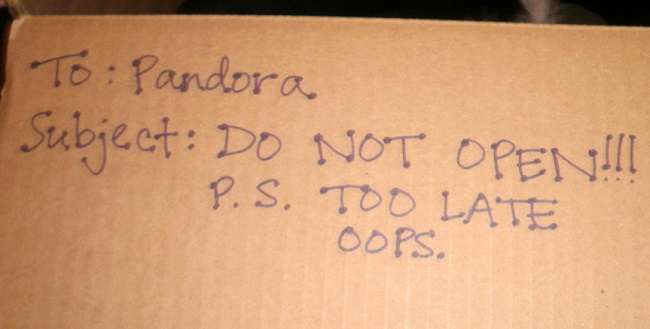

When asked by The Guardian if he regretted the years he spent smoking and drinking that might’ve led to his recent Stage 4 bout with throat cancer, Michael decided to go the TMI route and reply, “No, because this particular cancer is caused by HPV, which actually comes about from cunnilingus.”

Shhh! Did you hear that noise? That was the sound of his wife’s vagina, owned by gorgeous film star Catherine Zeta-Jones, snapping shut as firmly as a 1980’s Trapper Keeper.

But wait, Catherine! His days kneeling at your “altar” might not be done yet! He then followed through with this slip of the tongue: “But this cancer is cured by more cunnilingus. It giveth and it taketh.”

What a trouper. He GIVES a licking AND keeps ticking! Hip! Hip! Hooray? Hell NO!

The fact that Michael Douglas was once a pack-a-day smoker and was rumored to still be lighting up during his eight-week course of chemo and radiation treatment (much to his doctors’ dismay) seem to be insignificant details in his arrogant mind. According to him, his suffering was directly caused by all those Hooha Adversaries just jones’ing for some greedy pleasure! Even worse, what if all these Bitch-villains were only faking orgasms?? Michael the Martyr almost died IN VAIN!

Of course, this news story, wet and gorged with drama, won’t obliterate his acting career, just as the disease hasn’t killed the man. He’ll continue to land all those dope-with-a-dick roles, while Hollywood’s everlasting sexist, ageist plight will force all the older female actresses to battle the great Helen Mirren for the one or two juicy acting bones they get thrown. However, if as many method actors do, Douglas really delves into the psyche of his most current role — the legendary and notorious gay pianist Liberace — Michael will be licking something completely different. The media — and the entire world — wait with bated breath for the breaking news that he got his blight from some overblown BJ.

And if his current career ever does seem in jeopardy of becoming anti-climactic, I’m sure the Gardasil company will scoop him up to be their golden poster boy faster than a teen boy in his father’s car’s backseat car can find his girlfriend’s clitoris.

After all, SOMEONE needs to come to the rescue of that boy fatale! Our hero Mr. Douglas can snatch the boy’s tongue before it meets future doom — some villainess’s vajayjay — then guide him to his salvation!

And I think I speak for all women when I say truthfully: I can’t think of any better way to kill a man.

Addendum

Although we poke fun at Mr. Douglas’ slip of the tongue, we wish him and his family good health and continued recovery from his bout with oral cancer. It should be noted, that Mr. Douglas’ assertion that some oral cancer’s are linked to the HPV virus is correct. Additionally, the spouses of men with oral cancer, even with those whose cancer is linked to the HPV virus, generally do not carry the HPV virus themselves. Many oral cancers are also triggered or exacerbated by smoking and drinking.