Fertility Awareness Method For Contraception

Back in 2012, I was really sick and while we were trying to figure out what was going on, my doctor recommended I discontinue hormonal birth control for a while. For about 6 months, I used conductivity monitoring to avoid pregnancy. Each morning, I’d record the conductivity of my salivary and vaginal secretions looking for a change to indicate I was approaching ovulation and another change to indicate ovulation had occurred.

Back then, it felt confusing to me and a little black box”ish”, so when I was cleared to go back on hormonal birth control, I went back on it and didn’t give another thought to Fertility Awareness Methods (FAMs), until I decided to ditch hormonal birth control again.

This time, I did a deep dive and discovered new methods alongside familiar methods of FAM, and I went head-over-heels into the science of it.

In the decade since I relied on FAMs last, at-home urinary monitors are now available, and being a data driven girl, this is the method I opted for. Qualitative devices such as the ClearBlue Fertility Monitor (CBFM) didn’t quite offer the numbers I craved, so I went with the Mira Fertility Monitor even though, to date, no FAM endorses the use of this monitor for contraception (though Marquette University is actively testing the Mira against the CBFM with its protocols).

This ability to monitor your hormones at home also revolutionizes maintaining healthy hormonal balance and body literacy. Indeed, body literacy and the natural rise and fall of hormones throughout a healthy cycle is the topic of this post.

Hormones of the Menstrual Cycle

In this article, we will discuss:

- follicular phase and ovulation

- follicular development, how follicles are recruited and begin maturing throughout a woman’s reproductive life span

- how testosterone and estradiol are produced in the developing follicles

- the role of the hypothalamus and pituitary glands in follicular development and ovulation

- the role of progesterone in ovulation

- luteal phase

- key changes in hormone production during the luteal phase (second half of the cycle)

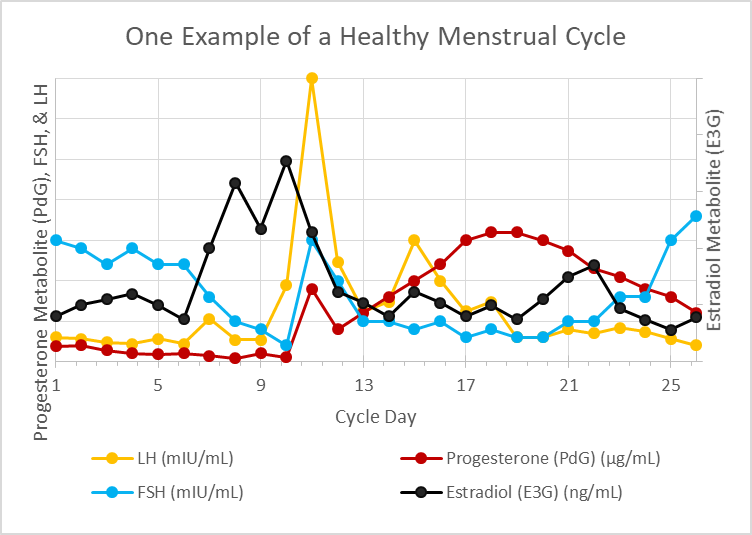

- finally, the entire menstrual cycle will be summarized in a single graph showing the rise and fall of hormones throughout the cycle

Why does all of this matter? When you understand how the menstrual cycle works, it becomes much easier to determine hormonal imbalances and much easier to navigate fertility. Women are only fertile for around a maximum of 5 days during any given menstrual cycle and when you have a condition like PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome) or experience delayed ovulation (or anovulation) for any reason during a cycle, menstrual cycle literacy makes it possible to pinpoint your fertile days when trying to conceive and naturally improve your chances of conception in each cycle.

For women who are not trying to conceive, cycle awareness is profoundly beneficial to overall health because you are better able to determine which part of your cycle is unhealthy and better able to address the underlying imbalance simply by knowing how your cycle works. Maintaining a healthy cycle throughout your reproductive years is of utmost importance even when your intention is to avoid pregnancy because the reproductive hormones impact every system within your body and are critical for everything from maintaining a healthy weight to a healthy heart.

This particular article (while containing lots of information) is an overview of the topics bulleted above. You will find a more in-depth discussion of these topics in this post.

An Overview of Follicular Development

Non-cyclical follicular development: Early follicular development of pre-antral follicles (follicles that don’t respond to follicular stimulating hormone) happens in a way that is not well understood by modern science and this part of follicular development is not governed by the menstrual cycle but instead occurs throughout a woman’s reproductive years beginning at the onset of puberty and ending with menopause.

Cyclical follicular development: A follicle is a structure within the ovary and it contains an ovum (immature egg). Each ovary houses several hundred thousand follicles at birth and throughout a woman’s reproductive life, these follicles mature and are responsible for releasing the reproductive hormones, estradiol and progesterone, which control release of these hormones:

- GnRH (gonadotropin releasing hormone) released by the hypothalamus in a pulsed pattern

- FSH (follicular stimulating hormone) released by the pituitary gland

- LH (luteinizing hormone) released by the pituitary gland

The brain’s role in follicular development and ovulation: The tempo at which GnRH releases from the hypothalamus controls the secretions of FSH and LH by the pituitary, and these two hormones influence ovarian hormone patterns and those ovarian hormones affect the tempo of GnRH pulses by the hypothalamus. This feedback loop is what the term, hypothalamic-pituitary-ovary (HPO) axis refers to. It is important to know about the brain’s involvement in follicular development and ovulation because when there is a problem with the menstrual cycle, practitioners generally look at where in this axis the misfire is occurring. Conditions like hypothalamic amenorrhea (HA) arise due to an issue with the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus and we will revisit this condition along with others caused by a dysregulation of hormonal release in the brain rather than the ovaries in future articles.

Selection of one follicle for ovulation: Once follicles have matured into antral follicles, further development is governed by FSH and the follicles need FSH to not only continue growing but also to prevent atresia (follicular death). More than one follicle matures during each menstrual cycle and because of the well-designed negative feedback between estradiol concentrations and FSH, the fastest growing follicle generally outcompetes all other follicles by releasing more estradiol, which then suppresses FSH production and starves out the remaining developing follicles. The dominant follicle survives this period of FSH famine because it has more FSH receptors. The additional FSH receptors make it better able to sequester the small amounts of FSH released at this time. It is also larger and has more energy reserves than smaller and slower growing follicles. This is why women typically release only one egg (mature ovum) at ovulation.

Testosterone and estradiol in follicular development: During follicular development, follicles produce both testosterone (and several other androgens [male hormones]) and estradiol (plus small amounts of estrone). The androgens are produced in the theca cell layers. The theca cell layers are not able to convert these androgens into estradiol or estrone because they lack the necessary enzymes. Instead, through diffusion, these androgens enter the granulosa cell layer of the follicle where the necessary enzymes are found (aromatase) to convert testosterone to estradiol and androstenedione to estrone. A separate enzyme converts the estrone into estradiol within the granulosa cells. In conditions like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), there is an imbalance in the androgen and estradiol ratio with higher levels of androgens suggesting a problem with conversion of these hormones in that condition. We will revisit this in future articles on PCOS.

Ovulation

Progesterone prompts ovulation. Historically, it was thought that the LH surge caused the follicle to release the mature ovum (egg) in a reversal of the negative feedback loop between estradiol and the pulse of GnRH which suppresses release of both FSH and LH from the pituitary. New research suggests that the adrenals release a small surge of progesterone that stimulates ovulation and prompts a rise in LH. This pathway explains why women who are under stress experience delayed ovulation.

Based on my own at-home hormone monitoring of urinary metabolites of estradiol and progesterone plus LH and FSH, I can confirm this pre-ovulatory temporal rise in progesterone. In fact, if this new theory proves correct, it may help explain the sudden shift in the electrolyte composition of vaginal secretions at ovulation.

Progesterone concentrations just prior to ovulation are much lower than concentrations mid-luteal phase, and so it is likely that the adrenal cortex, rather than the developing follicles, are producing the progesterone necessary to prompt the surge in luteinizing hormone (LH). It is also of note that high concentrations of progesterone (like those produced during the luteal phase and during pregnancy) inhibit ovulation. In in-vitro fertilization, when progesterone is given at doses to simulate the blood concentration seen during the luteal phase, this prompts the “vanishing follicle” phenomenon suggesting that a low progesterone concentration is vitally important to successful ovulation.

This theory may also explain why women under stress do not ovulate. It is common for women who develop a cold or illness during the peri-ovulatory phase to have either delayed ovulation or an anovulatory cycle. Other forms of stress (mental, over-exercise, disturbances to the circadian rhythm) are also known to delay ovulation. Considering that pregnenolone is the precursor to both cortisol and progesterone, this progesterone rise theory as the key event leading to ovulation evolutionarily fits the concept of conserving eggs or preventing reproduction when conditions aren’t favorable to pregnancy. Elevated demands for cortisol during times of high stress would deplete the body’s ability to create progesterone.

Role of LH: LH (luteinizing hormone) transforms the follicle into the corpus luteum. While the follicle primarily generated the hormones testosterone and estradiol throughout follicular development and leading up to ovulation, the corpus luteum releases progesterone and estradiol to maintain the uterine lining after ovulation.

Key Takeaways From the Luteal Phase and Menstruation

Progesterone released by the corpus luteum throughout the luteal phase is vitally important for pregnancy because it sustains the uterine lining providing nourishment to the developing embryo until the placenta fully forms around 12 weeks gestational age. It is especially important that concentrations of progesterone be maintained until implantation of the fertilized egg occurs. Luteal phase deficiencies, which we will talk about more in future posts, is one of the common causes of implantation failure.

In the absence of pregnancy, the corpus luteum atrophies between 10 and 16 days after ovulation. As the corpus luteum atrophies, levels of progesterone and estradiol both fall, resulting in atrophy of the uterine lining resulting in onset of menses.

An Overview of a Healthy Menstrual Cycle

In summary, a slowdown in the rate of release of GnRH from the hypothalamus prompts an increase in FSH secretion from the pituitary and this awakens further development in antral follicles within the ovaries. As these follicles mature, both testosterone and estradiol are made by the developing follicles increasing the amount of both these hormones within the body. Estradiol quickens the release rate of GnRH by the hypothalamus which reduces FSH secretions by the pituitary gland.

Historically, it was believed that once estradiol achieved a critical threshold, this negative feedback loop reverses, and FSH spikes along with an LH surge to cause ovulation. New research shows a transient rise in progesterone ahead of the LH surge. This rise in progesterone is about one-tenth the maximum rise in progesterone seen during the luteal phase of the cycle and is presumably produced by the adrenal cortex. If this theory (that a transient concentration-dependent rise in progesterone) prompts ovulation, then this better connects the dots between why stress and undereating cause anovulatory cycles.

Luteinizing hormone, which spikes around the time of ovulation, elicits key changes within the follicle allowing for rupture of the mature egg from the follicle and conversion of the follicle into the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum produces both progesterone and estradiol and in the absence of pregnancy naturally atrophies resulting in falling levels of progesterone and estradiol. As circulating blood concentrations of these two hormones, which are necessary for maintaining the uterine lining fall when the corpus luteum atrophies, the uterine lining itself also atrophies and sloughs off the walls of the uterus leading to the onset of menses between 10 and 18 days after ovulation in a healthy cycle.

In Summary

This very quick overview of the menstrual cycle (aka ovulation cycle) forms the basis of every single fertility awareness method (FAM) today. Whether the method involves monitoring changes in cervical mucus, cervical position, basal body temperature, electrolyte composition of salivary/vaginal secretions, and/or at-home urinary hormone monitoring, these methods are highly reliable for predicting ovulation and are so reliable that their efficacy for avoiding unplanned pregnancy vies that of hormonal birth control.

These methods are also invaluable for shining light on a woman’s reproductive health and elucidating where hormonal imbalance lies within her cycle when things are a bit off. FAMs also provide real time data for women who are tracking their cycles so that you are able to adjust diet and lifestyle to support hormonal balance.

I will refer back to this article often in future posts on FAMs and hormonal health.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, and like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash.