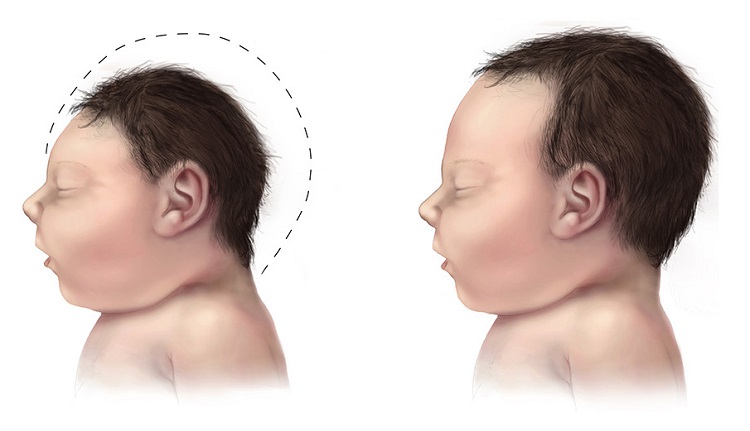

I have been studying thiamine metabolism since 1969 when I published the first case of thiamine dependency: Intermittent cerebellar ataxia associated with hyperpyruvic acidemia, hyperalaninemia, and hyperalaninuria. The case involved a 6-year old boy experiencing recurrent episodes of cerebellar ataxia (a brain disease resulting in complete loss of a sense of balance). These episodes, occurring intermittently, were naturally self-limiting without any treatment and were triggered by inoculation, mild head trauma, or a simple infection such as a cold. In other words, his episodes of ataxia were repeatedly initiated by an environmental factor. I have called each of these variable factors a “stressor”. Our studies showed that one of these stressors would unmask the true underlying latent thiamine dependency, falsely giving the impression that the stressor was the primary cause. This may be the principle of post vaccination disease in some cases. It may also be too easy to explain symptoms arising from trauma or infection as primary cause. These recurrent ataxic episodes were prevented from occurring by giving him mega-doses of a thiamine supplement.

Cerebellar Ataxia of Metabolic Origins?

When ataxia, as in this child, or other symptoms, occur intermittently, as they did in many other patients whom I would treat across my career, it is difficult to identify the true cause. The studies performed by neurologists, neurosurgeons and others inevitably would be normal, causing diagnostic confusion. In other patients with less serious symptoms, they are considered to be somehow feigned or of psychological origin. Symptoms that appear and disappear in a seemingly random manner and are not supported by conventional laboratory data are often explained this way. Please be aware that ataxia should never be regarded as psychosomatic. The point is that less serious symptoms that cause deviant behavior may not be recognized as biochemical changes in the brain.

With the present medical model, it is difficult to understand and accept that a stress factor can initiate the symptoms of a metabolically caused disease that has been relatively innocuous or silent until the stress is imposed. Let me give you another example.

Loss of Consciousness, Edema, Joint Pain: Rheumatic Disease or Metabolic Disorder

Since I was working at a multi-specialty clinic I was sitting having lunch with an ear, nose, throat (ENT) surgeon who knew of my interest in sudden death in infants (Treatment of threatened SIDS with megadose thiamine hydrochloride). He had been called to put in a tracheostomy to a middle-aged woman who had suddenly stopped breathing. Unlikely as it sounds, he suggested that I should go and look at the situation unofficially.

In the hierarchy of specialization, a pediatrician is not supposed to know anything about adult conditions, so I was not welcome. Because the internists who were taking care of her were rheumatologists, it was considered to be some kind of rheumatic disease, because of aches and pains in joints and limbs. She had had periods of unconsciousness over many years and her body was profoundly swollen, the hallmark of beriberi. Without going into details I was able to prove that this was indeed beriberi.

When I approached the rheumatologist who was her primary physician, I could not convince her of what appeared to her as too bizarre to contemplate. Notwithstanding, I had the cooperation with the nurses who followed my directions. When the patient was given injections of thiamine, she recovered consciousness and the gross body edema disappeared.

So fixed in the mind of many physicians is the concept that a vitamin related emergency simply does not occur, it was called “spontaneous remission” by my colleagues and “had nothing to do with vitamin therapy”. When I asked the rheumatologist whether we could conference the patient, she ignored the request. Well, this was not the end of the story.

Resolving One Deficiency Often Unmasks Another

After she started the injections of thiamine, with recovery of the nervous system, she began to develop a progressive anemia. It was considered by the internists to be internal bleeding and a thorough search produced only negative results. So ingrained is the negative attitude to vitamin therapy, I was even in fear that I might be blamed for causing the anemia. In the meantime, I took a specimen of urine and found a substance in the urine that suggested a deficiency of folic acid. Readers will remember that folic acid is a member of the B group of vitamins, as is thiamine. A blood test proved that she was indeed deficient in folic acid. When this vitamin was given to her, the anemia rapidly disappeared. This, believe it or not, still did not interest my colleagues.

She was discharged from the hospital, receiving supplements of thiamine and folic acid and her nervous system gradually improved. Some months later she developed a rash of a type that had been reported a few months previously as due to vitamin B12 deficiency. She was given an injection of vitamin B12 and over the next few days suffered slight fever and variable joint pains. These were symptoms with which she was familiar and had been responsible for the diagnosis of rheumatic disease. This sometimes happens temporarily with vitamin therapy, but often enough that I refer to it as “paradox”, meaning that things seem to be worse before they get better. Note that this paradox is not the same as side effects from a drug. The symptoms that cause a patient to see a doctor are temporarily exacerbated. With our present model the patient concludes that this is side effects from the vitamin(s) being used. I had to learn that paradox was the best sign that improvement would follow with persistence. She then continued on the thiamine, folic acid and vitamin B12.

The Role of Lifestyle and Diet Disease Expression – Oft Ignored Stressors

The fact that this woman was a chronic beer drinker and smoker had been ignored. They were, if you will, the “stressors” that were the dominant cause, perhaps impacting on genetic risk factors. The relationship between alcohol and thiamine deficiency is well known and so she had induced her own disease. Since there was a profound ignorance concerning vitamin deficiency diseases, the beriberi had been referred to by her internists as “rheumatic” in nature. This is because joint and limb pain, usually not recognized for what the pains represent, are often associated with compromised oxidative metabolism, either in the limb itself or in the brain where the pain is interpreted.

Defective oxidative metabolism caused in this patient’s case by thiamine deficiency, causes exaggerated brain perception. The brain induced a pain that gave the false impression that the disease originated in the joints and other parts of the body. Even if the origin of the pain is truly from a joint or muscle, defective oxidative metabolism in the brain will exaggerate the sense of pain perceived by the patient. Although this “phantom” pain is known as “hyperalgesia”, the mechanism is not well known as being due to compromised oxidation in the pain perception brain centers. Thiamine deficiency was responsible for the hyperalgesia experienced by the case of a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis that was posted recently on this website.

Beyond Thiamine: Multi-Nutrient Deficiencies

What interested me in the woman with beriberi was that folic acid deficiency was not revealed until her metabolism had been accelerated by the pharmacological use of thiamine. The folic acid deficiency then became clinically expressed as her metabolism “woke up”. It had been well known for some time that folic acid produced anemia would have to be treated with both folic acid and vitamin B12.

In the case of folic acid deficient Pernicious Anemia, if vitamin B12 was not given at the same time, the patient would develop a disease known as subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. Because I had forgotten this fact, I had neglected to give her vitamin B12 until it was finally expressed clinically in the form of a rash. Associating a skin rash with a vitamin deficiency is certainly not commonly accepted as a possible indicator of an underlying cause by physicians.

Vitamin Deficiency Versus Dependency

Returning to the case of the 6-year old boy discussed above, we learned over time that his health was dependent on high doses of thiamine to function. Believe it or not, this child required 600 mg of thiamine a day in order to prevent his episodes of illness. If he began to notice the beginning of an infection he would double the dose. The recommended daily allowance for thiamine is between one and 1.5 mg a day. Here, and in many other cases, huge doses of the vitamin are required in order to accomplish the physiologic effect. This represents what I call vitamin dependency.

Thiamine and magnesium, like many other vitamins, are known as cofactors to enzymes. An enzyme without its cofactor works inefficiently if it works at all. The “magic” of evolution has “invented” this cooperative action which is in itself under genetic control. In technical terms, the vitamin has to “bond” with the enzyme. If this bonding mechanism is genetically compromised, the concentration of the corresponding cofactor has to be increased enormously by supplementation in order to prevent the inevitable symptoms. You can see that this requires a clinical perspective tied to unusual biochemical knowledge. This is in complete contrast to what is usually regarded as vitamin deficiency, arising from insufficient concentrations in the diet.

What is perhaps not known sufficiently is that prolonged vitamin deficiency appears to affect this bonding mechanism. For example, it has long been known that to cure chronic beriberi, megadoses of thiamine are required for months. I have concluded that the megadoses of thiamine given by supplementation to a patient with long term symptoms arising from unrecognized deficiency appears to re-activate the inefficient enzyme. It is as though the enzyme has to be repeatedly exposed to megadoses of its cofactor to stimulate it and restore its lost function.

This may mean that even if the bonding mechanism is normal in chronic deficiency, enzyme function has simply decayed from lack of stimulation. This may explain why genetically determined dependency and long term dietary deficiency will produce the same clinical effect. The dosing of vitamins, if the clinical effects of deficiency are recognized, is not well understood in traditional western medicine. When insufficient doses are given and the symptoms fail to abate, the practitioner views it as evidence that supplements do not work.

Biochemical Diagnoses are Complex

I want the general public to begin to understand the principles that underlie the complexity of biochemical diagnosis. Perhaps a reader might find that a case like this is a reminder of a loved one whose illness was never understood after seeing many different specialists, all of whom were like the blind men and the elephant. Each was confined to his specialist status but none of them could see the overall big picture.

Reading these cases, you might easily come to the conclusion that they represent a rarity. Chronically unrecognized thiamine deficiency is common. Dependency is not uncommon. It is not as rare as is presently thought. Believe me, cases like these are surprisingly common and are responsible for a great deal of diagnostic confusion.

Vitamins are essential to consumption of oxygen in all life processes. To go against the principles of diet dictated by Mother Nature is a risk to life and limb that is not worth the derived pleasure. When limb pain is experienced without an obvious trauma, it is difficult to accept that it is because of inefficient use of oxidation in the brain, but that is exactly what we found.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.