Leuprolide, more commonly known as Lupron, is the GnRH agonist prescribed for endometriosis, uterine fibroids, cysts, undiagnosed pelvic pain, precocious puberty, during infertility treatments, to treat some cancers, and a host of other off-label uses. It induces a chemical castration in both women and men. In women, Lupron stops menstruation and ovulation and crashes endogenous estradiol synthesis rapidly and completely, inducing menopause and menopause-associated symptoms like hot flashes, sweats and osteoporosis, to name but a few. In men, where it is used as a treatment for prostate cancer, it prevents the synthesis of testosterone, pharmacologically castrating its users and evoking a similar constellation of symptoms.

Lupron for Endometriosis: Questionable Research

Lupron’s widespread use for pain-related, female reproductive disorders, such as endometriosis or fibroids is not well supported, with little research indicating its efficacy in reducing pain and no research delineating its effects on disease progression. Conversely, evidence of safety issues have long been recognized, especially within the patient communities where reports of chronic and life-altering side effects are common. We have many case reports on our site alone. Although, class-action and marketing lawsuits have arisen, Lupron continues to be mis-prescribed regularly to diagnose or treat pelvic pain disorders like endometriosis, generating over $700 million in revenue in 2010 and 2011 for the manufacturers and an array of serious and chronic health issue for its recipients.

The reported side effects of Lupron are staggering both in the breadth of physiological systems affected and the depth of symptom severity experienced (a partial list). Indeed, everything from the brain and nervous system to the musculature, skeletal, gastrointestinal and cardiac systems are affected by Lupron, sometimes irreversibly. This is in addition to thyroid, gallbladder and pancreatic side effects. How can one drug evoke so many seemingly disparate side effects? Is it possible that the magic of chemical castration is not as safe as we were led to believe; and that hormones regulate a myriad of functions beyond reproduction? It is.

Beyond Reproduction and Reproductive Disease

A major fallacy in medical science, and indeed medical research, is the total compartmentalization of physiological systems and by association an insoluble marriage of hormones to their respective reproductive organs, functions, and gender. Lupron, and drugs like it, were developed based upon this fallacy; that somehow suppressing estradiol and the other endogenous estrogens would affect solely the reproductive system. If only human physiology were that simple.

Hormones, even those inappropriately designated sex hormones, like estradiol and testosterone, regulate all manner of physiological adaptations in every tissue and organ in the body and they do so in conjunction with other hormones and by decidedly non-linear trajectories. That is, the dose-response functions are curvilinear where both too little and too much of a particular hormone can evoke serious negative consequences in body systems totally unrelated to reproduction. Chemical and surgical castration would fall into the ‘too little’ category.

Hormone Receptors are Ubiquitous

Hormones mediate these reactions via hormone receptors. Estrogen and androgen receptors are located throughout the brain and the nervous system, on the heart, in GI system, in fat cells, in immune cells, in muscle, the pancreas, the gallbladder, the liver, everywhere. When hormones bind to these receptors, whether they are membrane bound, nuclear, or other types, the hormone-receptor complex activates or deactivates what are called signal transduction pathways, essentially message lines. Those messaging lines tell the cell to do something. Too much or too little of any one type of hormone sends mixed messages, skewing cell behavior just slightly at first and when there are only small changes in hormone concentration, but with more chronic or more severe hormone changes, the signals become increasingly more deranged and the compensatory reactions, meant only for short term, become more exaggerated and self-perpetuating. This is where problems emerge. Even if estradiol or more appropriately, estrogens (there are many estrogens) feed endometriosis, tanking estradiol concentrations is dangerous and sets into motion complex reactions that we are only now beginning to understand.

Hormones Influence Everything

Since the hormones and receptors are broadly located throughout the body, it doesn’t take a genius to figure out that if we kill off one or more hormones completely, as Lupron does with estradiol, there are going to be negative effects globally, and they are likely to be pretty serious. So, even a surface level evaluation of the safety of drug like Lupron, would suggest a strong possibility of negative outcomes in regions of the body not associated with reproductive function. And with just a little bit of endocrinology under one’s belt, it should be clear that negative outcomes would compound over time, as additional reactions meant to compensate for short term changes in hormone concentrations, become increasingly entrenched and self-perpetuating, and in many cases, increasingly damaging to the health of the cells – but it isn’t. Despite the range of serious side effects, Lupron is a commonly and cavalierly prescribed drug and newer versions of Lupron like drugs are expected to take the market by storm.

Estradiol Is Critical to Human Health

While the pharmacological mechanism of action for Lupron and drugs like it is clear, they override pituitary control of the tropic hormones that signal the ovaries or testes to synthesize new hormones, how these drugs induce the array of side effects, many of them long term and even permanent, has not been explored as seriously as it should be. Certainly, one can hypothesize the effects of estradiol elimination on different systems based upon receptor distribution within each tissue and the signaling pathways therewith, but the effects are diverse and sometimes contradictory or highly tissue specific. One has to wonder if there might be a final common pathway by which the elimination of estradiol could disrupt multiple physiological systems in a predictably discriminate manner. Indeed, there might be.

Estradiol Regulates Mitochondrial Function: Mitochondria Regulate Everything Else

If you’ve read any of our articles over the last year, you’re aware that we have become increasingly interested in mitochondria, particularly how drugs and nutrients or nutrient deficiencies, impact mitochondrial functioning. Mitochondria take nutrients from food we eat and convert them to the biochemical energy required to power cellular life – ATP. Without appropriate cellular energy all sorts of things go wrong. Energy is fundamental to life and so functioning ATP pathways are critical for cellular and organismal health (and so is proper nutrition!). A number of disease states emerge when the mitochondria are damaged or inefficient at producing ATP, from chronic fatigue, muscle wasting and autonomic system dysregulation to name but a few. Estradiol, and likely other hormones, (most of the research focuses on estradiol), influences mitochondrial functioning and the production of ATP via a number of mechanisms.

Estradiol Is Needed for the Production of ATP

Though not a component of what is called the citric acid or TCA cycle or the electron transport chain (also called the mitochondrial respiratory chain), estradiol appears to be intimately involved in up – and down-regulating the enzymes and other proteins within those energy production cycles. Estradiol directly and indirectly modifies the types fuel used to produce ATP (glucose, fatty acids or proteins) and impacts the efficiency and flexibility with which ATP is produced. Essentially, estradiol impacts the substrate inputs and keeps the cogs in electron transport chain cycles moving. When estradiol is eliminated, fuel sources shift (by tissue) and those cogs, called complexes, begin to slow, become less efficient and send off more damage signals (reactive oxygen species – ROS) than can be effectively cleaned up. Since functioning mitochondria and sufficient ATP are required for cellular health in all cells, where energy demands are greatest, symptoms emerge: the brain and nervous system, the heart, the GI system, muscles, and bone formation/turnover.

In the brain, we see serious cognitive deficits and derangement of mood and perception with damaged mitochondria relative to estradiol elimination. We also see autonomic instability that impacts mood (flipping between depression and anxiety) but also heart rhythm and balance.

In the heart, the estradiol directly impacts mitochondrial fuel preferences and availability by regulating cardiac glucose and fatty acid metabolism. Without estradiol, the machinery within the mitochondria are not as flexible in their ability to switch between glucose, fat or proteins for precursor fuels to make ATP. The lack of flexibility, particularly during other physiological stressors, leads to impaired cardiac functioning and increased inflammation in affected tissues.

Bone formation is particularly hard hit as estradiol is required bone growth, maturation and turnover. Estradiol deficiency leads to increased osteoclast formation and enhanced bone resorption – destruction of bone or osteoporosis. Proper bone formation is also highly dependent upon vitamin D concentrations. Vitamin D deficiency leads to bone loss. Vitamin D activates estradiol synthesis, while estradiol activates vitamin D receptors. Lupron tanks estradiol and by association vitamin D, a double hit to bone health. At the level of the mitochondria, the third hit, reduced ATP, further damages bone health.

Estradiol is an Antioxidant

Antioxidants scavenge ROS. Antioxidants are needed to keep ROS concentrations at bay as too much ROS, though a natural byproduct of ATP production, will damage the mitochondria and initiate a damaging, self-perpetuating cycle. The body has a number of anti-oxidants to temper ROS. Many nutrients are included in this category: Vitamins C and E, CoEnzyme Q10 and glutathione are among the most well known. It turns out that estradiol and progesterone are potent anti-oxidants as well. So chemically or surgically eliminating estradiol reduces the body’s ability to detoxify and eliminate damaging ROS, evoking further mitochondrial damage.

Estradiol Modulates Mitochondrial Hormone Synthesis

That’s right, the mitochondrial estrogen receptors impact what is called steroidogenesis – steroid hormone synthesis – for multiple hormones, not just those pesky ‘female’ hormones. Like a thermostat that turns on or off when the temperature changes, mitochondrial estrogen (and other hormone) receptors sense hormone changes and up or downregulate the synthesis of pregnenolone (and the use of cholesterol to make pregnenolone). Pregnenolone is the precursor for all steroid hormones. So when Lupron or ovariectomy tank estradiol, not only is the synthesis of estrogens affected, but so too is the synthesis of other steroid hormones.

Estradiol Tempers Mitochondrial Ca2+ Homeostasis

Ca2+ balance is a complicated topic, a bit beyond the scope of this paper but is an important function modified by mitochondrial estrogen receptors. Ca2+ influx into cells is excitatory and turns on the cellular machinery. As one might expect, too much or too little Ca2+ activity could be damaging. Too much Ca2+ is cytotoxic or neurotoxic (if in the brain), killing the cells. The mitochondria are largely responsible for controlling the influx of Ca2+, sequestering Ca2+ when there is too much in order to save the cells. So when mitochondria become damaged or inefficient by any mechanism, Ca2+ homeostasis becomes an issue and cell death, tissue and organ damage become very real outcomes. Estradiol influences the mitochondria’s ability to sequester and temper Ca2+, so that the cells don’t become too turned on or over-active and die. (This is an interesting mechanism because estradiol itself is an excitatory hormone, increasing the activity of the cell when bound to the cell membrane or nuclear receptors but when bound to receptors on the mitochondria, estradiol tempers that excitation.)

Estradiol Regulates Immune Function

Estradiol bound to the estrogen receptors on immune and other cells activate and deactivate a number of signal transduction pathways that turn on/off inflammation and other immune responses. The mitochondria also regulate immune function via ROS signalling. Depletion of estradiol, particularly at the mitochondrial level, guarantees disrupted immune function and hyper inflammation by way of mitochondrial structural damage, derangement in function, and the loss of estradiol mediated anti-oxidant abilities. So by multiple mechanisms Lupron, drugs like it, and ovariectomy, damage mitochondria and initiate cascades of ill health.

Lupron, Maybe Not Such a Good Idea

Estradiol bound to mitochondrial receptors, controls a whole host of functions in the mitochondria, which then control cellular health throughout the brain and body. Without estradiol, the mitochondria become misshapen and dysfunctional and eventually die a messy death (necrosis), but not before inducing mutations in next generation mitochondria (mitochondrial life cycles include the regular birth of new mitochondria and the necessary death of old and damaged mitochondria). As the damage and mutations build and the ratio of healthy to damaged mitochondria shifts, cell death, tissue/organ damage and disease develop. Lupron, other drugs that tank estradiol, and ovariectomy, initiate mitochondrial damage. The mitochondrial damage represents a possible final common pathway by which Lupron induces the myriad of side-effects and adverse reactions associated with this drug.

A question that remains, is whether this damage can be offset by supporting mitochondrial machinery by other mechanisms. This is particularly important since millions of women have been exposed to Lupron and/or have had their ovaries removed. Other hormones and a myriad of nutrient factors are necessary for the enzymes within the mitochondrial machinery to work properly. Could we offset the damage evoked by too little (or too much) hormone by maximizing the efficiency of the other reactions. I think it is possible, at least theoretically and at least partially. That will be addressed in a subsequent post. For now, however, I think we ought to reconsider the use Lupron, other GnRH agonists, antagonists and the surgical removal of women’s ovaries. The damage evoked by eliminating estradiol is likely far greater than any potential benefit in an ill-understood disease process like endometriosis.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

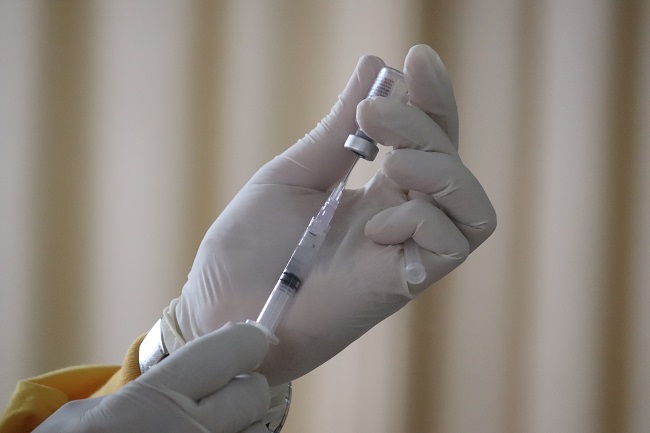

Photo by Mufid Majnun on Unsplash.

This article was first published on January 16, 2015.