‘Jo, you’ll be relieved to hear the tests are all normal.’

I’d heard this line so many times, and it wasn’t reassuring. Each time it became less likely that I had an illness that could be defined, diagnosed, and consequently cured, or even treated. If there was nothing wrong with me, why did I feel so awful? I had been gradually deteriorating over months, perhaps longer.

Fatigue and Other Seemingly Innocuous Symptoms

It’s difficult to say when I first felt unwell. One of the initial symptoms was terrific fatigue – struggling to find the energy to carry on each day at work. I was taking longer and more frequent tea breaks and relying on sugar to give me the buzz to carry on. Of course, it didn’t help that I didn’t sleep well. I would fall into a deep sleep early evening and then wake feeling strangely on edge with a racing heart, unable to sleep for most of the night. Even if I could sleep, it didn’t make me feel any better.

There were several other symptoms, which I could explain away, but one odd symptom was muscle twitches or fasciculations. These were worse when I was tired or had been more active. I also had dodgy guts – more about this later.

Even though I was exhausted I could continue working, being a mother to our four children – albeit a rather terrible one that repeatedly fell asleep in the middle of bedtime stories, until I developed brain fog. I felt like my thinking was occurring at less than half the usual speed. I struggled to hold a conversation, as this required listening, interpreting the other person’s words, formulating an answer, and talking. I would have to really concentrate to think about anything. I would forget things unless I wrote them down, which just meant I had unfinished lists scattered everywhere.

After falling on the ward where I had been working as a doctor, I finally acknowledged that I was sick, even if there was nothing apparently wrong with me. Once I stopped working, I deteriorated further, such that I was unable to recognize people and even places.

A Slow Road to Dementia

This was over 10 years ago. Clearly, I’ve improved since then. I’ve written a book to try to characterize my symptoms, explain what caused them, and why it was difficult to make a diagnosis. This seems even more pertinent since a lot of the symptoms I suffered with then resemble long Covid now.

My main concern was that I had developed dementia. I had many of the features: I struggled to remember recent events, I had problems following conversations, I was forgetting the names of friends and even commonly used objects, and I was repeating myself and having problems with thinking and reasoning. I also had difficulty recognizing where I was — this is visuospatial disorientation — a key marker of dementia.

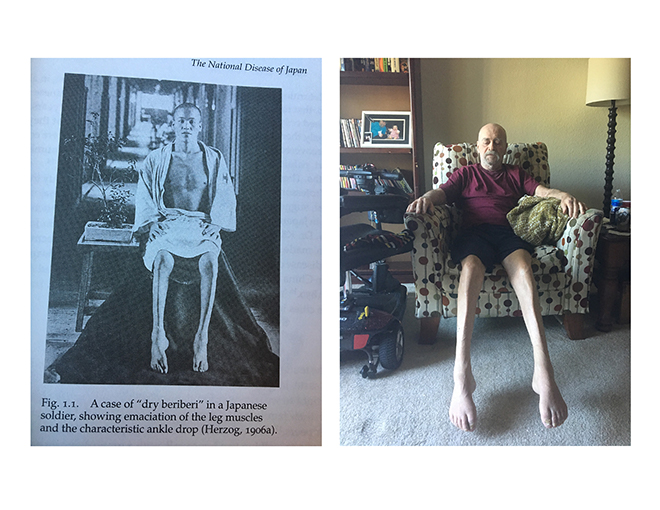

Since the medical profession seemed to have no idea how to treat me I decided to try to work it out for myself. What choice did I have? Away from work, I had time to slowly read through medical papers, whilst I rested. I recognized that my symptoms improved after taking antibiotics for a gum infection. Any exertion made me markedly worse, but not immediately afterward, it would be the following day and last for several days. I improved if I rested. My other symptoms included pains in my hands and feet. I thought this was arthritis initially, but when I developed pins and needles and subsequently numbness, I realized this was a peripheral neuropathy – a problem with the sensory nerves in my extremities.

Some months earlier a close colleague had told me I was thiamine deficient, mainly because I had lost a lot of weight. I was taken aback, assuming he thought my diet was poor, or that I was drinking alcohol. I hadn’t drunk any alcohol for years as it made me feel rough after a few sips. I investigated thiamine deficiency and found that it causes loss of sensation as well as loss of balance; I already knew it affected memory from treating alcoholics under my care.

My friend kindly agreed to try high-dose intravenous thiamine on the ward. Neither of us really thought it would work, but it was worth a shot. I was astounded when after a few minutes of the infusion I started to be able to think clearer and even the pains in my hands and feet disappeared. I practically skipped off the ward to buy oral thiamine and dose up. Sadly, thiamine tablets didn’t work and two days later I was back on the unit begging for more shots. This thrice-weekly dosing of thiamine infusions continued for months.

The Gut Connection

I trained in Gastroenterology and General Medicine. They say doctors make the worst patients. For as long as I could remember I had suffered from intermittent severe central abdominal pains, which usually occurred after eating quickly on an empty stomach. According to my mother, I had been a colicky baby and had also returned to the hospital as a new baby with uncontrollable vomiting. Nothing abnormal was found.

In fact, not all the tests I had were normal. After several second opinions, I had a few abnormal tests. I had a CT scan of my abdomen, which showed that I had gut malrotation. The severe pains I had experienced throughout life were due to small bowel volvulus – twisting. I learned that if I stopped eating and lay down on my back the pain would gradually subside. Each time my guts twisted scar tissue formed adhesions, slowing down my gut movements.

My guts had been noticeably abnormal for many years. I had noisy guts and passed very loose, frequent motions. I don’t know many slim 20-year-olds who suffered from severe gastro-esophageal reflux as I did. As this progressed, I developed recurrent chest infections and required multiple courses of antibiotics. Eventually, I worked out that I was aspirating gut contents into my lungs each night, and I stopped eating in the evening and propped myself up with many pillows. All sorted – no more chest infections – no more antibiotics.

One of the other abnormal tests was an incredibly low vitamin D. Through late-night searches of anything vaguely relevant and my gastroenterology knowledge I worked out that a low vitamin D occurred in bacterial overgrowth. This made sense. I had developed bacterial overgrowth in my small intestines — the part of the gut responsible for the absorption of nutrients from food.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or SIBO is due to an excess of bacteria in the small intestines. There are many risk factors including sluggish guts from adhesions, previous surgery, medications that slow the gut, but also multiple courses of antibiotics, poor immune system, and use of drugs that block acid production in the stomach, as well as pancreatitis. I’m sure that a diet high in sugar didn’t help.

I had another test specifically looking for bacterial overgrowth, which the nurse (a colleague I’d worked with many times) and I interpreted as abnormal. The consultant I saw thought the machine must have broken. This was frustrating; after so many normal tests to have a wildly abnormal test attributed to faulty equipment. I decided it was better to treat the patient (me) rather than a dubious test result. After starting antibiotics, I no longer needed the thiamine infusions. The diarrhea also improved.

I worked out that I had bacterial overgrowth from mal-rotated guts, obstructed from adhesions, which improved with antibiotics and were eventually treated with corrective surgery. I also had severe vitamin D deficiency, which was corrected with injections, and thiamine deficiency, which I subsequently managed with a fat-soluble thiamine analogue — benfotiamine. I found a paper online reporting thiamine deficiency in extremely obese patients who had undergone surgery on their small intestines to aid weight loss. Many of these patients had thiamine deficiency; they also had high folate, which was thought to be a marker of bacterial overgrowth. Oral thiamine had no effect on their thiamine levels, but after taking antibiotics the patients’ thiamine returned to normal. Interestingly, my folate was high.

What was less well known was that some bacteria produce an enzyme called thiaminase, which destroys thiamine. I can only assume that I had these kinds of bacteria in my gut. Interestingly these bacterial enzymes do not destroy benfotiamine.

I followed up on my theory of the underlying cause of dementia: that too many bacteria, producing a lot of thiaminase enzyme, destroy the thiamine in our food rendering us thiamine deficient. I found out that thiamine is essential for all living things, and it is necessary for the release of energy from food, particularly sugar or glucose. The brain only uses glucose as an energy supply. There are reports of low thiamine levels in the brain in patients who have died of dementia. Glucose metabolism in the brain is never normal in dementia. Benfotiamine has been shown to improve mild cognitive impairment. I speculated that this was the cause of my brain fog.

Thiamine Deficiency: The Missed Diagnosis

Why was it so difficult to make a diagnosis? I believe there are several reasons. Firstly, thiamine levels are rarely tested in the UK. Even though I had worked in the NHS for over 20 years I had never requested a thiamine test. Secondly, thiamine deficiency is known to present in widely differing ways. This is like many of the mysterious syndromes — a constellation of recognizable symptoms and signs with largely normal tests: irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, etc., and also long Covid. Thirdly, I wasn’t listened to. I’m not sure whether this is because I’m female, but I became extremely sick before anyone really tried to help, and even then I was reliant on friends I have in the medical profession.

I’m remarkably well now. I regained my memory and ability to think, although it probably took a couple of years. My guts still aren’t completely normal, but bacterial overgrowth is often a chronic condition. I still take supplements and I’m careful with my diet, avoiding sugar and alcohol. My diet is quite restrictive, but it’s worth it. I wouldn’t want to go back to how I was.

#1

15 customer reviews

Books

15 customer reviews

Books

Last updated on December 28, 2023 at 6:07 pm – Image source: Amazon Affiliate Program. All statements without guarantee.

Last updated on December 28, 2023 at 6:07 pm – Image source: Amazon Affiliate Program. All statements without guarantee.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, and like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Photo by Katie Moum on Unsplash.

This article was published originally on June 30, 2022.