Obviously, you can survive without a gallbladder. Otherwise, gallbladder removal (cholecystectomy) would not be such a common surgery. In fact, over 600,000 people in the U.S. have their gallbladders removed yearly. However, surviving without an organ and living a healthy life without it are two very different things.

Following a cholecystectomy, you are more prone to developing certain health problems. For example, you are at greater risk of developing a fatty liver, diarrhea, constipation, biliary issues, indigestion and developing deficiencies of essential fatty acids and fat soluble nutrients. Bile, which is necessary for digesting fats and proteins and metabolizing fat soluble vitamins and minerals, is no longer stored and concentrated in the gallbladder. This can lead to unpleasant symptoms.

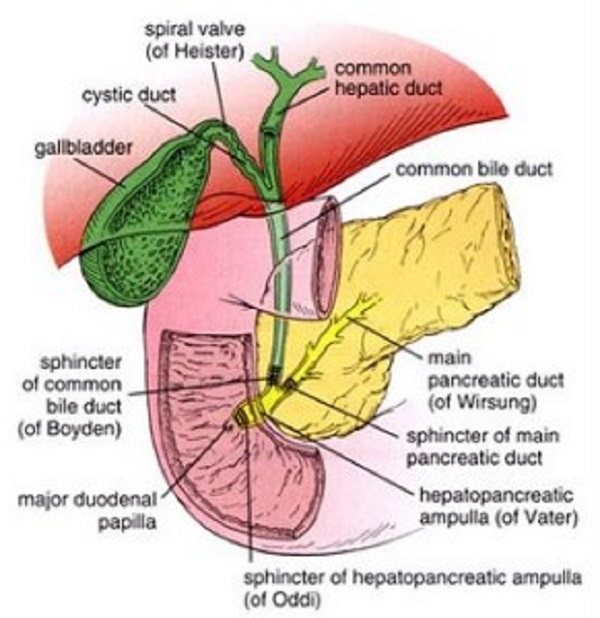

When your body is void of a gallbladder, bile freely flows from the liver to the bile duct, exiting through the sphincter of Oddi into the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). The high-water content of bile is no longer removed and overly concentrated bile is not conjugated in the gallbladder.

Change in bile chemistry isn’t the only thing that occurs after cholecystectomy. Surgeries are never perfect and fool-proof. Therefore, human error can bring about injury to the ducts. Adhesions (scar tissue) can form following surgery and some people are more prone to developing them. A remnant cystic duct (the duct that once connected the gallbladder to the common bile duct) may cause problems. Also, dramatic changes may occur within the liver itself due to the absence of a gallbladder.

Any health issues or symptoms arising because of gallbladder removal is called postcholecystectomy syndrome. Postcholecystectomy syndrome describes the appearance of symptoms after cholecystectomy. It is widely estimated 10-15% of the population experience some form of postcholecystectomy syndrome, but Merck Manual estimates anywhere from 5-40% of cholecystectomy patients are afflicted. Isn’t it interesting that a seemingly disposable organ could wreak such havoc on our bodies once it is removed?

The most common causes of postcholecystectomy syndrome relate to the change in bile flow and concentration, complications from surgery (i.e. adhesions, cystic duct remnant, common duct injury), retained gallstones or microscopic gallstones (biliary sludge), effect on sphincter of Oddi function, and excessive bile that is malabsorbed in the intestines. Jensen, et al described in their research paper, Postcholecystectomy Syndrome, over 60 different etiologies of postcholecystectomy syndrome.

Diagnosing Postcholecystectomy Syndrome

If you are experiencing troubling symptoms following a cholecystectomy, talk to your gastroenterologist or primary care doctor. He/she will likely order blood work, specifically liver function tests. In addition, you may want to ask that your vitamin and pancreatic enzyme levels be tested, since bile is required to metabolize fat soluble vitamins like vitamins A, D, E and K; and some postcholecystectomy issues affect pancreatic enzyme output.

Depending on the results of your bloodwork, your doctor may order an imaging study (x-ray, ultrasound, MRI, or CT scan), a functional test (gastric emptying study or small bowel follow-through) or a procedural test (endoscopy, colonoscopy, barium enema). If these tests are inconclusive, your doctor may want to conduct a more in-depth procedural test like an endoscopic ultrasound or Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to get a better look at the ducts, liver, and pancreas. In rare cases, your doctor may recommend exploratory surgery.

There are also alternative tests a naturopath or functional medicine practitioner could offer, i.e. comprehensive stool analysis, or hormone and nutritional tests. Keep in mind that for some postcholecystectomy patients, the answers to your symptoms may not be revealed in typical bloodwork, scans, or procedures. Tests are not fool-proof for all patients. Many patients have disabling symptoms and their bloodwork and scans are normal. “Normal” test results can come as a relief. However, when you do not get an answer to your woes, it can be quite frustrating. This does not mean, though, you can’t treat your symptoms.

Treating Postcholecystectomy Syndrome

The most common postcholecystectomy issue is bile acid diarrhea. Because bile is being dumped and no longer processed, the intestines receive an excess of bile or bile that is difficult to reabsorb. This may cause moderate to severe diarrhea in some people, especially after eating.

Ask your gastroenterologist or primary care doctor about prescribing cholestyramine, a bile acid binder. It will bind the bile acids and, in most cases, reduce this form of diarrhea. Always pay attention to side effects like constipation, bloating, or flatulence to gauge how much cholestyramine is appropriate for your individual situation. If the cause of your diarrhea originates from bile, cholestyramine will likely help you. If the cause of your diarrhea is from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or another cause, this therapy will not be effective. For other forms of diarrhea, you may need an IBS-specific medication or natural therapy.

Another postcholecystectomy issue, mostly affecting women, is Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction (SOD). SOD symptoms are upper right quadrant pain, nausea/vomiting, bowel, and other issues. For more information on this condition, read my article, Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction, or go to the SOD Awareness and Eduction Network website. In addition, I published The Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction Survival Guide this past summer.

Microscopic gallstones and biliary sludge can cause problems too, but is difficult to diagnose unless you have an ERCP. If you have constipation, upper right quadrant pain, and nausea, you may have biliary sludge. If you and your doctor suspect this, he may want to prescribe ursodeoxycholic acid, which reduces the cholesterol content in bile. Alternatively, an ERCP can clean out the duct.

Consult with a natural health practitioner if you’d rather go the holistic route. He/she can prescribe the essential fatty acids Omega 3 and 6 (bile is needed to convert these fatty acids), digestive enzymes, a bile replacement supplement, homeopathic remedies, and/or herbs (ex. dandelion, milk thistle, turmeric, peppermint, and bitters). In addition, chiropractic, acupuncture and Chinese medicine, and other natural therapies have helped people with postcholecystectomy syndrome.

General Diet and Lifestyle Remedies

After I had my gallbladder removed, I had to change my eating habits to avoid unpleasant symptoms. Overeating spelled disaster for my strained liver, pancreas, and ducts. It is best to try to eat several small meals a day or eat smaller portions at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Going too long without eating is also bad as our bodies signal bile to be released at certain times of the day. Not eating can lead to bile acid diarrhea and intestinal discomfort.

Don’t eat fast. Instead, chew your food thoroughly and take your time. This will benefit your entire digestive tract and organs so they don’t have to work as hard. Your digestive system starts in your mouth where enzymes are released to start the digestion process. Taking the time to allow these enzymes to mix with your food is essential for proper and thorough digestion.

Eat a low-fat diet. This does not mean you should avoid all fats. Instead, be mindful of the amount of fat grams you ingest, especially saturated fats. The Mayo Clinic recommends keeping fat intake under 3 grams per meal and snack. Greasy, fried food may no longer be your friend. It is wise to hold off on re-introducing fatty foods high in saturated fats. If you don’t, you may experience pain, gas, or diarrhea. Some of the worst offenders, besides fried foods, are cheese, fatty luncheon meats or sausages, hot dogs, fatty pieces of steak, dark meat portions of poultry, butter, and all oils except medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) oils. MCT oils, i.e. coconut and palm kernel oil, do not require bile for digestion.

The juice of certain vegetables can do wonders for the liver and biliary system. Beets, apples, and ginger all support bile formation. Beets are probably the best vegetable for your liver as they contain important liver healing substances, including betaine, betalains, fiber, iron, betacyanin, folate, and betanin.

Betaine is the substance that encourages the liver cells to get rid of toxins. Additionally, betaine acts to defend the liver and bile ducts, which are important if the liver is to function properly. Additionally, beets have been linked to the healing of the liver, a decrease in homocysteine, an improvement in stomach acid production, prevention of the formation of free-radicals in LDL, and the prevention of lung, liver, skin, spleen, and colon cancer.

Apples contain malic acid which helps to open the bile ducts that run through your liver and reportedly soften and release the stones. Apples are also high in pectin. Ginger is reported to increase gut motility and bile production. You can add ginger to food dishes or eat it raw. I prefer to juice ginger and drink a small amount of the extract. The extract can also be added to juiced fruits and vegetables. Be careful, though, as it is spicy and pungent. You only need a small amount.

Other foods reported to protect the liver and increase bile production are bitter foods such as dandelion and mustard greens, radishes, artichokes, fruits high in vitamin c, and cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage.

Stay tuned for my next book, Living Well Without a Gallbladder: A Guide to Postcholecystectomy Syndrome, which will be published Summer 2017.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

This article was published originally on January 30, 2017.