For as long as I have been studying endometriosis, I have suspected that endometriosis represented a protective cascade, one that has either gone awry or was incapable of fully eliminating or adapting to an internal stressor. To me, endometriosis behaves like cancer, not the cancer of aberrant oncogenes and tumor suppressors, though they are factors, but the cancer of metabolism, of Otto Warburg and others. I think aberrant metabolism is the key to understanding endometriosis and a myriad of other disease processes, including heavy menstrual bleeding. Until recently, however, I have not had much evidence to support this hypothesis. There is a troubling paucity of research on topics related to women’s health. Of the research that exists, much of it is focused on tried and mostly untrue conventional interpretations disease. Interpretations, I would argue, that do more to serve economic or political purposes than health, but I digress.

Over the last few years, however, mitochondrial metabolism has emerged as key determinant of health or disease. Central to this work is the role of cellular hypoxia. In order for cells to function, in order for our brains to think, our hearts to pump, muscles to contract, the mitochondria, organelles within the cells, must breathe. That is, they must consume oxygen and respire. Mitochondrial oxygen consumption results in the critically important production of ATP – cellular energy. Without oxygen, no ATP. Without ATP, nothing works. Cells die. Tissues die. Organs fail. Whether and how quickly injury or death ensues is determined by a number of factors, including the totality of the oxygen deprivation, but also, the metabolic flexibility to withstand insufficient oxygenation, even at low levels. Mitochondrial metabolism can be derailed quite easily by diet, pharmaceutical and environmental chemicals, and even a sedentary lifestyle. Metabolic alterations may transpire across generations when exposures are coincident with critical periods of fetal development and even result in de novo or first generation mutations in either nDNA or mtDNA. Mitochondrial metabolism is a key determinant of health and may in fact determine whether and how oxygenation is maintained at the cellular level.

Hypoxia and the HIF Survival Cascades

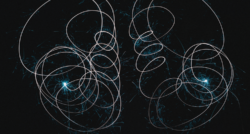

Adequate oxygenation in the cell involves a system of molecular adaptations that kick into gear during periods of hypoxia and remit when oxygenation returns. These survival cascades are initiated by oxygen sensors that trigger a set of proteins called hypoxia inducible factors (HIF1α and its counterparts HIF1β, HIF2α, HIF3α). HIFs are the master regulators of oxygen homeostasis, ensuring cell survival during periods of low oxygen. So far, researchers have identified at least 100 other proteins controlled by HIFs and tasked with bringing more oxygen and fuel into the cells. HIFs activate angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels), erythropoiesis (production of new blood cells) and iron metabolism (oxygen carriers), glucose metabolism (substrate for ATP), growth factors, and other proteins. When all else fails, the HIF system signals apoptosis, cell death. In the short term, the hypoxia cascades are brilliant in their ability to forestall anoxia and death. In the long term, however, they wreak havoc.

If you have followed the endometriosis research, most if not all of the proteins involved in maintaining and spreading endometriotic lesions are controlled by HIF proteins. I suspect they were activated by disturbed mitochondrial metabolism, either causatively or consequently. Owing to the laws of reciprocity, once hypoxia sets in, it will disturb mitochondrial metabolism further, initiating a downward spiral that becomes difficult to unwind without full consideration of mitochondrial function. Of interest, these same cascades are active in preeclampsia and other diseases of modernity. In fact, I think many of the diseases we see in western cultures, are a result of long-term, low-level, cellular hypoxia mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction.

What precipitates the hypoxia and the mitochondrial dysfunction is not clear, but here again, I have some ideas. With endometriosis I suspect there are multiple factors that coalesce to generate cell level hypoxia. Fetal and germ cell damage of our grandmothers and mothers mitigated by environmental (here, here, here) and/or pharmaceutical toxicants combined with our own exposures are key among them. For the heavy menstrual bleeding, however, I think the origins are almost entirely environmental, and by environmental, I mean the totality of the modern environment that includes diet, pharmaceuticals, and the ever-present industrial and environmental chemicals that pervade our existence.

With endometriosis, the hypoxia cascades are hyperactive. That is, HIF proteins are more prominent and seem not to be degraded effectively, suggesting a chronic or unremitting hypoxic threat. The ever-present HIF proteins then activate the compensatory cascades discussed above, promoting endometriotic lesion growth and the invasion into healthy cells. In contrast, with heavy menstrual bleeding researchers have found lower levels of HIF proteins. On the surface, this might suggest hypoxia is not involved, but I suspect it is. I just don’t know how exactly. There are hints to suggest I am correct. The question is why are the HIF proteins lower in women who bleed more heavily and higher in women with endometriosis? Is the bleeding another mechanism to deal with an unresolved localized hypoxia; one mediated perhaps by a different hormonal milieu?

Hypoxic Spirals and Mitochondrial Metabolism

In either case, aberrant HIF tells us that mitochondrial metabolism is altered. What it does not tell us is why or how. In many regards, however, the why and how may not matter. There are so many factors capable of affecting mitochondrial metabolism that determining THE factor is all but meaningless and perhaps a fool’s errand inasmuch as mitochondrial phenotypes even with the same genotypes are rarely consistent. More often than not, mitochondrial symptoms express with tremendous variability even among family members. This owes largely to the fact that mitochondria, as the cell danger sensors, are malleable by just about everything from nutritional status to genetics to environmental exposures and anything in between. In fact, something as simple as a nutrient deficiency, even a low-level one, can induce mitochondrial hypoxia. Carried out across time, the disease processes evoked appear identical to their genetic counterparts, and can induce de novo mutations generationally, effectively blurring the once hard and fast distinctions between genetic and environmental disease processes.

High calorie malnutrition, diets high in sugars and processed foods loaded in environmental chemicals but deficient in actual nutrients induce hypoxia. Many of agricultural, industrial and medical chemicals have been linked directly to endometriosis. Generationally, the effects are compounded. Consider DDT, Dioxins, PBCs, and DES. All are genotoxic, damage mitochondria and have been linked to endometriosis. Linkages to heavy menstrual bleeding are less well known, due to a complete lack of research. However, if we consider fibroids are one the most common causes of heavy menstrual bleeding, rodent research shows clear connections between long term, low level, food exposures to glyphosate, Bt toxin, and adjuvants, the chemical cocktail found in Roundup and used on genetically modified crops, to fibroid tumor growth. I suspect the accumulation of these and other toxins are keys to understanding the cell level hypoxia associated with heavy menstrual bleeding. The fibroid, like the endometriotic implant, may represent a mechanism to sequester toxicants, or in the case of heritable damage, remediate a flaw in bioenergetics with the resulting hypoxia a side-effect that then initiates its own survival cascades – the hypoxic spiral.

Hypoxic spirals are quite easy to initiate but somewhat difficult to stop, especially when resource availability is limited because of genetic or environmental liabilities. Consider the self-perpetuating cascades in iron deficiency or anemia, common in women. Anemia induces cell level hypoxia, which induces heavy bleeding. The heavy bleeding then induces or maintains the anemia. Similarly, Lupron, a medication used for both endometriosis and fibroids causes cell level hypoxia directly by damaging the mitochondria and reducing their metabolic flexibility. Hormonal contraceptives do as well. Indeed, one could argue that since all medications and vaccines damage the mitochondria by some mechanism or another, the ability to consume oxygen is necessarily impaired by modern therapeutics for all who use these chemicals. Reproductive ailments may simply be one set of manifestations among many. This begs the question, however, if cellular hypoxia can be induced so easily, in virtually anyone, why is it that some women develop endometriosis and/or heavy menstrual bleeding and others do not. In other words, why aren’t all women plagued with these disease processes? Increasingly, they are.

Damage to female reproductive function, colloquially referred to as ‘period problems’, has become almost commonplace in modern cultures affecting some 80% of the female population. Whether the issues present as endometriosis, adenomyosis, PCOS, fibroids, heavy bleeding or other menstrual or reproductive disease processes, may not matter. The nexus of each may be indicative of cell level hypoxia with the different phenotypes contingent on the individual’s cocktail of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental exposures and resources.

Treatment Possibilities

If hypoxia lay at the root of these disease processes, to the extent that the hypoxia can be resolved affords new treatment opportunities; ones that not only tackle root causes, rather than symptoms, but may also affect the totality of the individual’s health. Hypoxia, barring obstruction, is a metabolic disturbance. Whether the origins are genetic, epigenetic or environmental, metabolism resides in the mitochondria. If we support the mitochondria, provide the mitochondria with the resources, the fuel to perform the tasks they are proscribed to perform, rather than continually damaging or blocking innate signaling pathways needed for cell survival, we may just be able to, if not eliminate these disease processes, at least manage them and improve quality of life. I think this is worth looking into, don’t you?

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Graphic credits: Tony Grist (Photographer’s own files) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

This article was originally published on May 9, 2017.