I’m not doing so well in my role as lab rat as of late. I’m expecting the powers that be will soon be calling me back on the carpet. I’m getting used to that. Being told to do one thing and then doing another never gets a hand clap from the overlords of medicine, so I’ve discovered.

It started with the multiple diagnosis’s a year after I was first put in the cage for the “experiment”. I can remember it like it was yesterday. The pursed lips of disapproval and those side shifting eyes. I didn’t get it back then. I was too preoccupied with my devastation to notice. I see now how futile my efforts were in trying to assist them. That kind of behavior will get you a special label and believe me, their kind of special is not a pleasant one.

It’s hard adjusting to being in a cage after years of freedom. The overlords don’t seem to get that fact. For them it’s all numbers and weights and measures and instruments that poke and prod. There’s a lot of heading shaking and nodding and hands on chins while they observe my reactions and record my symptoms. I can see it in their eyes. The data is not adding up. They don’t know how to interpret what they are seeing but I remain silent….at first.

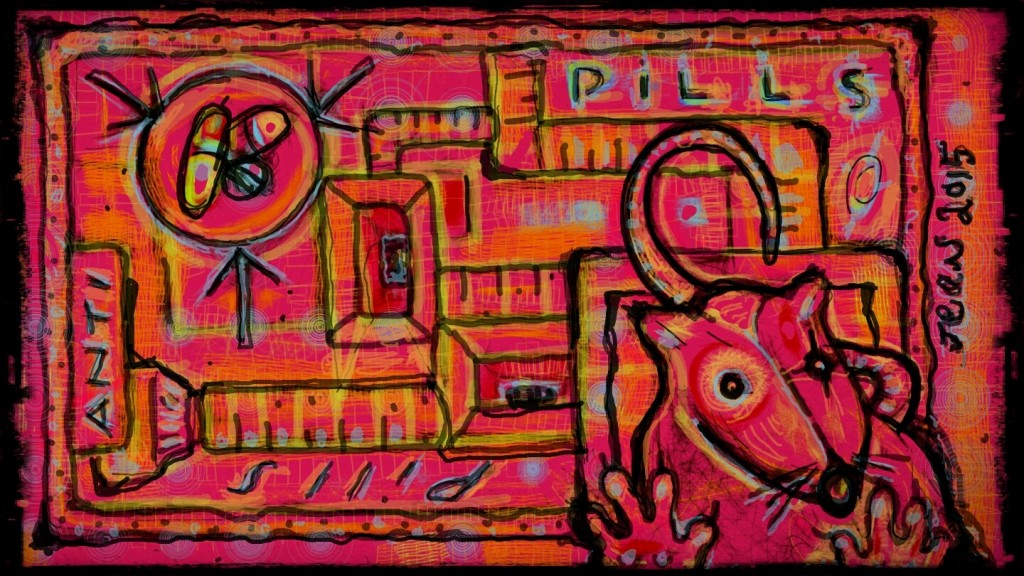

I’m busy adjusting…adapting to what has become my new prison. I’m busy in my head connecting dots. Still reeling from the shock of being caught. Still taking stock of the damage they have wrought on me with their potions and notions and endless pills. Each tentative step forward fraught with trepidation and my silent anger. Their white lab coats have become a symbol of their surrender to my angry eyes but as always they soldier on in the pursuit of science.

Marking and measuring symptomologies, feigning a knowingness I know they don’t possess. After all, isn’t that how I ended up here, on the weight of their duplicity?

I’m not alone in this cage but I’m alone in myself. I am beginning to understand that I am just one cog in an endless wheel that they have created. A Frankenrat, crippled and ever mutating under the power of their chemistry, as they silently observe. I can feel myself shrinking under their disapproving gaze but it’s only a momentary slip. I retreat inside myself. I become invisible, silent and still.

I watch the watchers…waiting for that perfect moment…that golden opportunity I know is coming. Every day is a new day I tell myself. Every day that I wake up and draw a breath is another day I have won. I may be a lab rat but I am no longer their lab rat. I dream of the day when all of the lab rat nation will rise up as one and our voices will be heard. That’s the beauty of experiments…one never really knows what the outcome will be.

We Need Your Help

Hormones Matter needs funding now. Our research funding was cut recently and because of our commitment to independent health research and journalism unbiased by commercial interests, we allow minimal advertising on the site. That means all funding must come from you, our readers. Don’t let Hormones Matter die.

Yes, I’d like to support Hormones Matter

This post was published originally December 1, 2015.