Endometriosis is a painful, chronic, inflammatory condition that is poorly understood but affects more than 1 in 10 women and an uncounted number of gender diverse people. Previous articles have discussed endometriosis in general and some of the specific symptoms and complications that may arise. Hallmark symptoms include painful periods, painful bowel movements, and painful sex. Fatigue is another major symptom associated with endometriosis, and one which is frequently discounted by physicians due to it being such a challenging symptom to objectively measure. Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis is diagnostic laparoscopy, and the gold standard for treatment is laparoscopic excision.

In this interview, Philippa Bridge-Cook, an international endometriosis advocate, describes how the disease of endometriosis involves tissue that is similar to the lining of the uterus, which grows outside of the uterus. Often this tissue is in the pelvic area, but can also be in other parts of the body completely unrelated to gynecologic structures. These tissue growths are inflammatory and can be hormone-responsive, meaning that often people with endometriosis experience increased pain during menstruation, which can be severe and debilitating. However, endometriosis has much wider-reaching consequences “just” period pain.

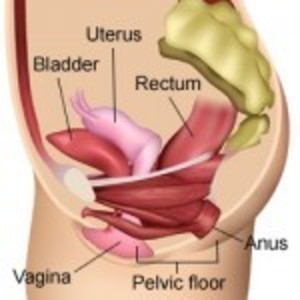

Painful bowel movements may occur due to the location of these lesions, either on or within the bowels, or surrounding structures. They may also be related to chronic inflammation in the body. Digestive difficulties may extend beyond pain and include severe bloating, gas, painful cramping, and sensations of fullness, food sensitivities, diarrhea or constipation.

Painful sex can occur and may be related to either the location of these pain-producing lesions (for example, if they are in a place that is directly affected by sexual contact, and therefore directly irritated), or it may be related to pelvic floor dysfunction that arises due to chronic pain. Pain may be experienced during arousal, sexual touch, sexual penetration, orgasm, or after sexual activity.

As a Doctor of Physical Therapy, this specific complication of endometriosis falls squarely into my wheelhouse, and I treat many patients who are suffering from pelvic floor dysfunction related to chronic pain. In this interview, Philippa and I talk about how the pelvic floor muscles (muscles in the area of the groin that control urination, defecation, and contribute to sexual function) can become tense and tender due to the stress of chronic pelvic pain. During sexual activity they may be painful to touch, painful to penetration, or painful when they contract reflexively during orgasm. I discuss physical therapy for sexual pain here (link: Physical Therapy for Female Sexual Pain).

Dr. Bridge-Cook discusses not only the generalities of endometriosis and endo-related sexual pain, but also actionable, specific strategies for charting symptoms, speaking with your physician, and pain management. She reviews different imaging techniques, surgical techniques, and incomplete/inaccurate treatments. She is a true expert in the subject, informed by her years of personal experience as well as her extensive research and advocacy work. She speaks in a way that is easy to understand and provides hope, closing by encouraging women to not give up and to seek help with physicians that are willing to take them seriously.

Endometriosis and Sexual Pain

Share Your Endometriosis Story

Endometriosis affects millions of women but goes largely undiagnosed for years and treatment options are limited. To raise awareness about endometriosis and build the knowledge base, we need your help. Share your experience and your knowledge about living with endometriosis. To learn more, click here and send us a note.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Photo by Alexander Krivitskiy on Unsplash.