She was insy tinsy, curled up in a comfy ball. When she was happy, she did summersaults in the amniotic fluid, with plenty of room to spare. She had no idea, but first she went to the left, and then she swooned to the right, floating with pure bliss. There was no yesterday, and no tomorrow. There was only “now.”

Sometimes, she could hear a bigger voice, sometimes calm and sometimes yelling and screaming. With the screaming came a faster heart rate, pounding her ears and making her own heart beat pound!-pound!-pound! … beating faster and faster itself.

Then there were the nights. She didn’t know they were ‘nights’ per se, but she knew that when things got dark, the sound of the lady crying would start again and again. Over and over she would hear the crying, feel a hand over the wall covering her, making her shake and shake and shake all over again. Every night. The sobs scared her, making her crawl up in a ball as tight as she could get. She just wanted to disappear, to be invisible, to be nonexistent because she was made to feel so unwanted. Her mother never sang to her, never put Mozart music on her belly, never gave her a backrub from her buttocks to her head. So she never knew what she missed. She was just cold. She knew coldness.

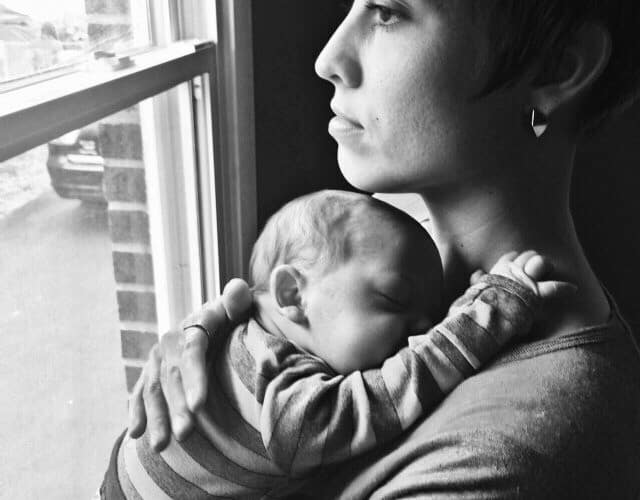

On the other side of the wall, her mother was crying again, mascara blobs leaving black eyes as if she was in a bar-room fight. Her hair was dirty; she hadn’t bathed in a week. Her belly was big and she was running out of clothes to wear, down to the last pair of sweatpants. She couldn’t go to sleep and instead, she was tossing and turning from side to side, dragging the baby in the abdomen with her with a plop! to each side. And she woke up all night, on and off. Early morning awakening was all too common, with the mother up long before the sun rose. Her eyes burned from sleeplessness, tearing without crying. Crying without tearing. She felt that she was in a brain fog; she was boiled down to pure misery. How is she supposed to live like this?

She walked out to the apartment balcony, five stories up, and she toyed with the idea. She toyed with the idea of climbing up the balcony and jumping off, just to end it all. She wasn’t capable of caring for herself, let alone a baby. She would take the baby with her as she jumped, to spare her any more harm in this harsh world. She toyed with the idea, and then she slumped her shoulders, failure that she was, because she failed at everything and today would just be another day of failure. She turned around and walked away, towards the bed. Then she shut the sliding glass door on the way back in, locking it as if for safekeeping. She forced herself to eat, for the baby’s sake.

Weeks went by. Eventually, alone and in the darkness, she passed the mucous plug. Then the amniotic fluid broke, leaving a huge pile of wetness on the sheets and floor as she dragged herself to call 911 on the speakerphone.

Fluid still running down her leg, she just lay there crying real tears this time, wondering what she was supposed to do with a new baby girl. She was afraid she would throw her out the balcony. She was afraid she would sleep on top of her and crush her. She knew she wasn’t in her normal state, but she didn’t know what to do, whom to ask for help, what would happen, or what was wrong with her.

She didn’t know whom to call.

Her uterus contracted hard now that they were in an operating room, pushing the baby’s head down toward the cervical os and therefore, the outside world. In the meantime, the little baby’s head pressed flat on its way out of the vagina as she reluctantly made her way out to the outside world. She heard many voices, and the Cling! Clang! of metal instruments being thrown here and there. It hurt her ears! It shocked her!

It was cold, harsh, and they scrubbed all the wonderful, warm amniotic fluid solution off her with a cold, wet towel. She frowned at them with distaste. Then they laid her on a cold, hard scale, they pricked her foot for blood, and she screamed. It was just the beginning. She screamed and screamed and screamed.

After a few days, it was time for Mom to take the baby home. Everyone else was happier for Mom than she was for herself. The baby cried for her breast milk, and Mom whipped out a boob every two hours. Tired, sleepless, undernourished, Mom was wheeled out of the hospital with no balloons and no flowers. Her friend drove her home after ensuring the baby car seat was intact.

Mom’s sleeplessness continued. Her thoughts of throwing the baby out of the window resurfaced, her guilt and panic ensued when the baby cried, and this went on for months. No one knew. She didn’t have any friends. She wanted to jump off the ledge with the baby.

Disheveled, she went grocery shopping. She had no glow on her face at being a new Mom, and you were the first to notice. So you struck up a conversation with her, pushing yourself into her life, almost against her will. But not really. Because secretly, she wanted you there, and inwardly, she yearned to have you there. You offered to babysit one night, exchanged phone numbers, and you called her the next day to ask her if she needed anything from the drug store. Any shampoo? Baby lotion?

And the more you talked to her, the more you discovered a probable diagnosis. So you gave her an ‘800’ number to call, and she did it. And she was one of the few women who got the diagnosis made, received treatment, intervention, and after about one year, she was cured. What was her diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Postpartum depression. Also known as maternal mental illness, it is more varied and common than previously thought, perhaps occurring in one of five pregnant women (Gaynes, 2005). During pregnancy, the etiology is due to hormonal complexity involving stress, hormones, and genes, wherein some endocrine hormones can go up greater than a hundredfold (Sichel, 2003). After childbirth, hormone levels fall to the ground, resulting in another hormonal insult swinging in the opposite direction. Sounds like a roller coaster to me, or the giant tick-tock of a ginormous grandfather clock, with a huge pendulum swinging two different ways. Either way, one could easily see it makes one prone to get sick.

So, maternal mental illness does not just occur in the postpartum period of up to one year (Belluck, 2014). It can occur during pregnancy. It is often accompanied with social isolation and/or it overlaps with common symptoms of pregnancy itself, confounding the diagnosis even more. There are a paucity of studies that include the screening, multi-ethnic, diverse socioeconomic status, pre- and post-partum depression assessment (e.g., “mild” vs. “severe” depression), the institution of an intervention, and the follow-up of the effectiveness of the intervention. Nevertheless, there are a variety of Resources and Help Sites available to turn to for use (Belluck, 2014).

The following states have actually passed laws for screening, education, and treatment of maternal mental illness, in an attempt to prevent baby drownings and maternal suicides: Texas, New Jersey, Illinois, and Virginia. New York is considering such legislation. Patient awareness and standardized physician questionnaires are needed to assess risk, not only of depression.

In this author’s view, every pregnant woman needs and deserves the assessment of the risks of: being battered, suffering emotional abuse, forming diagnostic criteria for diagnosing mental illness including maternal mental illness and/or psychosis, infanticide due to maternal mental illness, nutritional status, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Improved medical education should also ensue. For the women that are seeking prenatal care, the gynecologist is poised to be the “Gatekeeper”. Psychiatry should be front-runners in grading maternal mental illness through the DSM-V, and should take “front and center” in leading this riveting cause for women and their babies.

About the Author: Dr. Margaret Aranda is a USC medical school graduate, as well as an anesthesiology resident and critical care Fellow graduate of Stanford. After a tragic car accident in 2006, she unfolded her passion of writing to advance the cause of health and wellness for girls and women. You can read more of her work on her personal blog, Dr. Margaret Aranda, her Pinterest page, a page on Postpartum Depression, her author’s page at Tate Publishing or follow Dr. Aranda on twitter @DrM_ArandaMD.

References

- Belluck, P. ‘Thinking of Ways to Harm Her’. New findings on timing and range of maternal mental illness. Postpartum Depression. Mother’s Mind: First of Two Articles. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/16/health/thinking-of-ways-to-harm-her.html?_r=0. June 15, 2014 (Accessed June16, 2014).

- Belluck, P. ‘Thinking of Ways to Harm Her’. New findings on timing and range of maternal mental illness. Postpartum Depression. Mother’s Mind: First of Two Articles. Resources: Where to turn for help with maternal mental illness. The New York Times. June 15, 2014 (Accessed June 16, 2014).

- Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, Brody S, Miller WC. Perinatal Depression: Prevalence, Screening Accuracy, and Screening Outcomes. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 119. (Prepared by the RTI-University of North Carolina; Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No. 290-02-0016.) AHRQ Publication No. 05-E006-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2005.2 (Accessed June 16, 2014).

- Sichel, DA. Neurohormonal aspects of postpartum depression and psychosis, in Infanticide: Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers who Kill. Edited by Spinelli MG. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003, pp 61-80.