A subject near and dear to my mom-scientist’s heart is the rapid increase and over-use of prescription medications during pregnancy. In the span of about 30 years, we’ve moved from a strong, and perhaps more medically prudent, tradition of no medication, no caffeine, no alcohol while pregnant, to 70–80% of women taking at least one prescription medication during pregnancy.

The Rise in Prescription Medications During Pregnancy

According a report by the CDC, between 1976-2008 prescription medication use during pregnancy grew at a staggering rate.

- 60% increase in first trimester prescription medication use

- The number of women taking >4 prescription medications while pregnant has tripled

- The number of women taking anti-depressants while pregnant has increased significantly

- 1 in 33 babies are born with birth defects

On average, American women are taking 2.3 medications during pregnancy and sometimes more. I cannot help but wondering when we became so unhealthy.

Prescription Opiates During Pregnancy

More recently, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that 13,500 babies are born every year with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome or NAS. NAS is a polite way of describing children who are born addicted to the pain killers that were, at least originally, prescribed by physicians to their pregnant mothers. Infants who, in their first moments of life outside the womb, must endure the suffering of opiate withdrawal.

Anti-depressants During Pregnancy

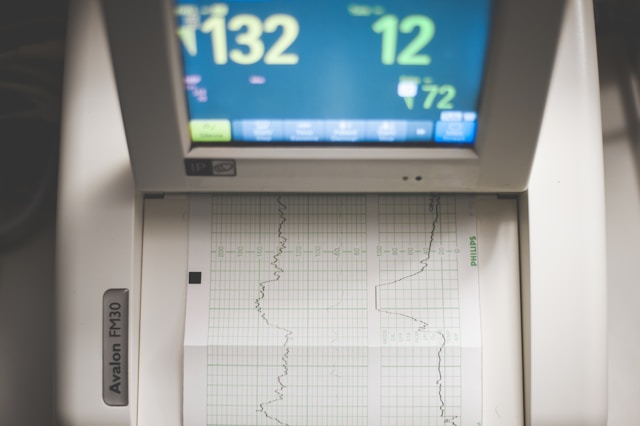

A similar abstinence syndrome is observed in infants born to women taking prescribed selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI) anti-depressants. It’s called newborn behavioral syndrome, another overly benign name that describes the tremors, agitation, excessive crying, respiratory difficulties, and seizures that emerge post birth as an infant withdraws from SSRIs. This is addition to the increased risk of congenital heart malformations, Long QT syndrome and Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension, that are associated with SSRI infants.

Take Back Pregnancy

Much of this increase can be attributed to the brilliance of pharma’s mega-marketing machine, but the culpability for the consequences lay with us. Women make 80% of all family medical decisions. We are the deciders for health. We have bought into the notion that a pill cures what ails us. Sometimes it is true. Often times is it not. It is incumbent upon us to know the difference, especially during pregnancy. Many women do not realize that:

Medications do not metabolize the same way in a pregnant versus non-pregnant woman

Most medications cross the placental barrier

Drug testing is not done on pregnant women

So we often have no idea what works, does not work and what the true risk and severity of the side effects will be until after the medication hits the market. Even then, the true risks are difficult to discern because of the glut of medical marketing that often discredits the early reports.

Marketing Prescription Medications To Physicians and Consumers

Just because a medication is prescribed by a physician or it can be purchased over-the-counter, does not make it safe. All medications have side-effects and most of those are not well-understood during pregnancy. In the case of anti-depressants during pregnancy, study after study, after study, after study (here, here, here) has been published showing the adverse effects of these medications during pregnancy. Indeed, another two were published just recently, linking anti-depressants to pre-term birth and infant convulsions. And yet, the conventional wisdom has been, and is still, that treating depression during pregnancy pharmacologically will improve pregnancy outcome.

“Depression treatment during pregnancy is essential. If you have untreated depression, you might not have the energy to take good care of yourself. You might not seek optimal prenatal care or eat the healthy foods your baby needs to thrive. You might turn to smoking or drinking alcohol. The result could be premature birth, low birth weight or other problems for the baby — and an increased risk of postpartum depression for you, as well as difficulty bonding with the baby.”

The data have not born that out. Even the FDA , though they acknowledge the serious adverse events associated with SSRIs during pregnancy,

“FDA Drug Safety Communication: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) anti-depressant use during pregnancy and reports of a rare heart and lung condition in newborn babies.”

they recommend no changes in prescribing practices.

“At this time, FDA advises health care professionals not to alter their current clinical practice of treating depression during pregnancy. Healthcare professionals should report any adverse events involving SSRIs to the FDA MedWatch Program.”

What Is a Girl To Do?

Learn a little chemistry, understand basic statistics, read and research every medication you take, even when you are not pregnant, but especially when you are, and most importantly, make educated choices about your health, your child’s health and the health of your family.

Photo by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash.

This article was published originally on Hormones Matter in September of 2012. I am sad to say, the problem has only become worse.