I was told I did not need my gallbladder – that it was a nonessential organ. Hearing that from a surgeon convinced me to have it removed to rid me of abdominal discomfort and nausea. An ultrasound showed some gallstones, but no other reason for removing the organ was presented to me. I was 29 years old and not a savvy patient like I am today. I didn’t ask questions or seek alternative treatments or a second opinion. I was a working mom with no time to be sick. “Just take it out,” I said.

That “non-essential” organ proved to be very essential for my body. Immediately following the procedure and for the next 14 years, I suffered from severe pain in my right side, nausea, and a multitude of other disabling symptoms. I was eventually diagnosed with Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction (SOD), a condition where estimates of 75-98% of sufferers are women. The majority become afflicted after their gallbladder has been removed. As such, many of us with SOD regret having had this operation.

What Does the Gallbladder Do?

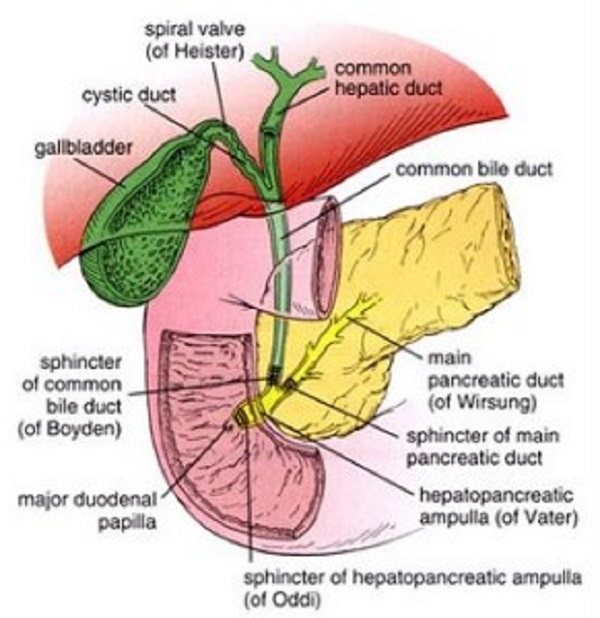

The gallbladder is a small organ that stores the bile produced by the liver. After a fatty meal, the body releases a hormone known as CCK that signals the gallbladder to release bile. Then the bile flows down the bile duct into the small intestine to emulsify and digest fats. The liver, where the bile is produced, also uses bile and the gallbladder to remove toxins from the environment, food, and other wastes. The bile stored and delivered by the gallbladder is different from the bile created and secreted by the liver. Bile in the gallbladder is more concentrated due to its removal of some water and electrolytes.

Gallbladder Removal (aka Cholecystectomy)

Over half a million people in the United States have their gallbladders removed every year. Clearly, it is a booming business. The common reasons for cholecystectomy are:

- Gallstones (cholelithiasis)

- Infected or inflamed gallbladder (cholecystitis)

- Non-functioning or under-functioning gallbladder

- Blocked bile ducts (ex. sludge or scarring)

- Cancer and congenital defects (less common)

As you can see in some cases it is in the best interest of the patient to undergo cholecystectomy. However, some develop secondary symptoms that are worse than their original gallbladder symptoms.

Postcholecystectomy Syndrome—Symptoms to Consider

New symptoms may arise following a cholecystectomy. This is known as a postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS). It is estimated that 10-20% of cholecystectomy patients develop PCS. Without the function of the gallbladder in place, some of the problems patients experience range from annoying to life-threatening, ex. abdominal pain, bile diarrhea, bile reflux, gastritis, IBS, pancreatitis, liver disease, and what I have–SOD—where the pancreatic and biliary valves do not open and close properly. At the time of this writing, an excellent overview of the various PCS complications and more information about PCS can be found in the Medscape article, “Postcholecystectomy Syndrome.”

The Gallbladder and Hormone Connection

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, the prevalence of gallstones is higher in women than men. Female sex hormones adversely influence bile secretion from the liver and gallbladder function. Estrogens increase biliary cholesterol saturation (the main ingredient for gallstones) and diminish bile salt secretion, while increased progesterone may lead to inhibition of the contraction of the gallbladder, reducing bile salt secretion and impairing gallbladder emptying. Due to fluctuating hormones women experience during pregnancy, it is not uncommon for women to develop gallstones during this time or shortly thereafter.

Alternatives to Cholecystectomy or “I Wish I Knew Then What I Know Now”

You can prevent gallbladder problems in many ways. Eat a diet low in saturated fats and sugars. Avoid crash diets. Try to eat whole foods rather than processed products with multiple ingredients (especially those with ingredients you can’t pronounce). Exercise. If you are on birth control or hormone replacement therapy, talk with your doctor about the effects they may have on your gallbladder. If they are unsure, your neighborhood pharmacist may be helpful or ask for a referral to someone who may be able to help answer your questions.

If you already have gallbladder issues, here are some alternatives to cholecystectomy to consider:

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): a non-surgical procedure used to remove stones, sludge, treat SOD, place stents or apply balloon dilatation to widen the bile duct, and use special X-rays for diagnostic purposes.

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL): uses high-frequency sound waves to shatter cholesterol gallstones into pieces small enough to pass through the bile ducts into the intestines.

- Ursodiol: a medication that suppresses cholesterol production in the liver, reducing the amount of cholesterol in bile.

- For women: seek out a functional MD or naturopath to get your hormones in check naturally.

- Supplements and Herbs: I recommend only taking these under the care of a naturopath, herbalist, traditional Chinese medicine practitioner, or other alternative healthcare providers knowledgeable in the benefits and side effects of such medicinals.

Be leery of Internet claims to cure your gallbladder issues. For example, I did not list gallbladder flushes as for some people, these can be very dangerous.

Gallbladder symptoms can be quite disabling and prompt anyone to run to an operating room table for relief. If your symptoms are tolerable, try alternative therapies and talk with your doctor about ERCP, ESWL, and Ursodiol as alternatives. However, if your well-being and life depend on having your gallbladder removed, take what your doctor says very seriously.

Image: Laboratoires Servier, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

This article was published previously on Hormones Matter in March of 2015.