I was asked by several people to write about statins. There is much confusing information about what they are, what they can be used for, how they work, and why they help—or rather, do they help at all. So here I give my assessment of statins, hopefully helping in creating a clearer picture.

Disclaimer: I am not an MD and am not making any recommendations, not giving any advice, and am not diagnosing anyone by writing this article. This article contains my thoughts, my opinion, my views, and should not be used as a basis for your decision. Consult your physician before you make any changes to your medicines. Any harm that may accrue to anyone as a result of this article is not the responsibility of this blog or the author. Neither the blog nor the author can be held liable.

With this said, you may want to take this paper to your doctor to discuss what you do or do not need. There is much new information about heart disease, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction (MI), cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, strokes, metabolic disease; chances are that your doctor could use a little help. The aim of this article is to synthesize relevant information and to connect the dots.

Is There Anyone Who Doesn’t Need Statins?

This is a much more important question than recognized. I would argue that most people do not need statins. In fact, let me rephrase that: very few people need statins. This view is contrary to the current push to place more and more people on statins.

I am reading the book “A Statin Nation – Damaging Millions in a Brave New Post-Health World” by Dr. Malcolm Kendrick (I highly recommend it!), in which I found a fascinating quote from an article titled “The Last Well Person” by Klifton K. Meador, M.D. in The New England Journal of Medicine1 (it is behind paywall here for those with access), in which he wrote:

The demands of the public for definitive wellness are colliding with the public’s belief in a diagnostic system that can find only disease. A public in dogged pursuit of the unobtainable, combined with clinicians whose tools are powerful enough to find very small lesions, is a setup for diagnostic excess. And false positives are the arithmetically certain result of applying a disease-defining system to a population that is mostly well.

What is paradoxical about our awesome diagnostic power is that we do not have a test to distinguish a well person from a sick one. Wellness cannot be screened for. There is no substance in blood or urine whose level is reliably high or low in well people. No radiologic shadows or images indicate wellness. There is no tissue that can undergo biopsy to prove a person is well. Wellness cannot be measured… If the behavior of doctors and the public continues unabated, eventually every well person will be labeled sick. (page 1)

In some sense, I could now finish this article and say this is all I have to say about the need for statins. You need to understand that you do not have statin deficiency.

But I know that I would get a lot of raised eyebrows from doctors who regularly prescribe statins; from people whose doctors ordered them to take statins; and, undoubtedly, there are many readers who will either be totally confused or will say “what nonsense”, so I will continue and expand on this message.

Between the Number Needed to Treat and the Number Needed to Harm Lays the Truth

Number Needed to Treat (NNT) and Number Needed to Harm (NNH) are very important numbers but rarely mentioned in discussions about drug safety. The NNT tells us how many people need to be treated with a medicine in order for one person to gain any benefit from that medicine; the smaller the NNT, the better. In contrast, the NNH tells us how many people will be treated before one person is harmed by that drug; the larger the NNH, the better.

A study from 2017 summarized several studies and showed the NNT and NNH for statins, based on actual trials. The bottom line:

Importantly, despite the small reductions in nonfatal heart attacks and strokes, statins were not associated with a reduction in serious illness overall … Although statins provide a significant reduction in mortality in high-risk groups, this benefit has not been shown in lower-risk groups. (emphasis is mine)

In clinical trials, researchers only enroll subjects who are most likely to benefit from taking the medicine—meaning they don’t place healthy people on statins in a clinical trial. If they had also included healthy people or people with CVD who would not likely to benefit from statins (those with a congenital condition) in these trials, the harm-ratio would increase. If you are not likely to benefit from statins but you decide to take them anyway, it is a much more likely outcome for you to be harmed.

The NNTs for statins were: 250, 217, 313, etc., where 217 is the best outcome, meaning 217 people have to take the drug for 1 person to benefit. The NNH in these trials was 21 or 4.8% (1/21= 4.8%) for short term, and 204 or 0.49% (1/204=0.49%) for over 5 years taking statins. Thus, between 0.49% and 4.8% of the people treated with statins will sustain some harm depending on treatment length. This means that 1 person per every 21 treated will sustain some harm with short term use and 1 in 204 over 5 years. You may wonder why the NNH number is increasing (harm reducing) over time.

This can have many reasons. For example, initially many people who are put on statins may experience significant adverse events, which get reported to the FDA’s adverse events database (please report all adverse events you have here). Knowing the many adverse events assists in selecting those patients who must take statins and are more likely to benefit, or the benefit outweighs the potential harm. Furthermore, over time, drug interactions may become evident and people who take statin-interacting medicines will not be placed on statins, reducing the adverse events and harm drug interaction with statins may cause. And one more important point: statins interfere with CoQ10 production, an essential element for energy and the heart—see more discussion about this later. Some doctors may prescribe statins with CoQ10 and those patients perhaps experience more benefit and less harm.

The NNT for a treatment-benefiting a person at best is 217, meaning that 1/217 people will likely benefit=0.46% and, put this in another way, 99.54% will get no benefit at all.

This should immediately stop you in your tracks. After all, if you are treated and are the one of 21 who is harmed or one of the 217 who is taking statins but without any benefit, you will end up wishing you had not taken any statins. What are the chances that you will end up with a fatal cardiac event if you don’t take statins? And if 99.54% of the people who take statins don’t benefit, would you be better off not taking statins in the first place?

Noteworthy is that statins are prescribed to a lot of people who don’t have heart disease or any form of cardiovascular disease. Some doctors go as far as recommending adding statins to drinking water, yet they don’t not want to take it themselves. Studies on children with genetic hypercholesteremia show that taking statins from as young as age 8 did not help prevent the later outcome of atherosclerosis and will require surgery later in their lives to repair their arterial walls.

Statins have serious side effects–over 300 have been found. Hundreds of clinical trials studies are summarized in this paper, which particularly highlights these adverse effect:

- Muscle damage (myotoxicity)

- Nerve damage (neurotoxicity)

- Liver damage (hepatoxocity)

- Endocrine disruption (hormones that run the whole body)

- Cancer-promoting

- Diabetes-promoting (metabolic syndrome)

- Cardiovascular-damaging (the very thing statins are taken to prevent)

- Birth defect-causing (teratogenic)

Let’s look at this further from the standpoint of heart disease, in general; what is heart disease? Is high cholesterol the same as heart disease? Does lowering cholesterol really help prevent heart disease?

What is Heart Disease?

Heart disease is referred to by various names: as a type of cardiovascular disease (CVD), atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, heart attack, metabolic disease, etc. The list is long.

Note one important thing though: I didn’t list high cholesterol as a heart disease. That is because high cholesterol does not mean heart disease. It means high cholesterol. Not all people with high cholesterol get heart disease and not all people who get heart disease have high cholesterol. Since statins only lower cholesterol, this doesn’t automatically mean that they prevent heart disease. High cholesterol refers to two things: high total cholesterol or high LDL.

What is Cholesterol?

There is a great description and complete explanation of cholesterol here. Cholesterol is vital to the human body and performs several major functions. As a building block of every cell, it is a main hormone producing agent. It also helps in digestion. Over 20% of our cholesterol is in our brain, where it helps in the formation of myelin, an important insulating material around every single nerve cell, and cholesterol also prevents diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Our body would not make cholesterol if we did not need it.

In a standard lab lipid tests, we “measure” total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides. LDL and HDL are lipoprotein balls (not cholesterol) that carry cholesterol and other vital elements in them. LDL carries fat-soluble vitamins and minerals like calcium, vitamin D, K2, and others2, so it really is not in anyone’s interest to lower LDL. A reduced LDL will immediately reduce these vital micronutrients as well, causing harm. HDL carries cholesterol fragments—think of HDL as a sponge that soaks up unwanted extra cholesterol, fats, and other fragments. HDL returns these to the liver to be reprocessed or eliminated. Reducing HDL is not a good thing and increasing HDL too much is also not a good thing because it may sponge up too much LDL and other fragments, before they had any chance to do any good.

Triglycerides are three fat molecules held by a glycerol head. Since they are not cholesterol, statins usually have no effect on triglycerides. Yet, most studies point to the problem of high triglycerides. Too low triglycerides can also pose a health risk—or be a sign of a disease.

High Cholesterol

Total cholesterol is the sum of LDL, HDL and (triglycerides/5). There are many assumptions here, and most of those are incorrect—I just list 3 relevant incorrect assumptions.

- Assumption 1: high LDL means high “bad cholesterol”.

- Assumption 2: high HDL means high “good cholesterol”, though since it increases the total cholesterol and high total cholesterol is bad, this implies that one should not have high HDL.

- Assumption 3: LDL, HDL, and triglycerides are cholesterol—none of them is.

And if your HDL is high (what is considered to be the good cholesterol), those doctors who only look at total cholesterol (and there are many of those!) will want to put you on statins and that will harm you.

High LDL?

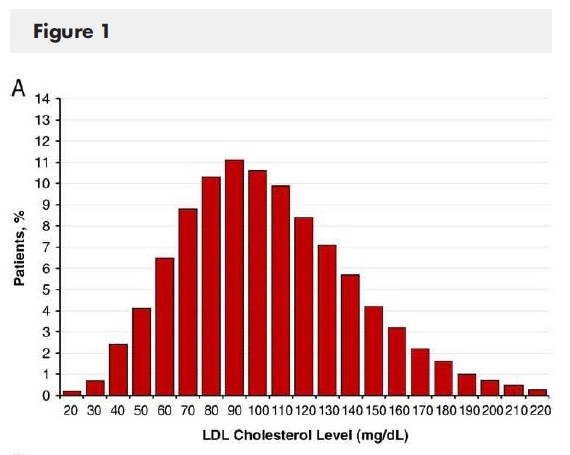

It is not the amount of LDL that matters but rather what kind of cholesterol your LDL is stuffed with. A paper titled “Lipid levels in patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease: An analysis of 136,905 hospitalizations in Get With The Guidelines3 (here) introduces us to something super cool. They documented the lipid levels of 136,905 patents from hospitalizations from 541 hospitals, where admission lipid levels were collected. They looked at the lipid levels and the cardiac events. The below graph is only the LDL on a Bell curve:

Image from here.

The horizontal axis shows the mean (average) LDL cholesterol of the persons admitted, and the vertical axis shows the number of people with a cardiac event with the particular LDL levels. Note the paradox: more people with the recommended LDL levels tended to have cardiac events than those with the higher LDL levels. Significantly fewer people had a cardiac event with an LDL of 200 than with an LDL of 90! Today, the recommended LDL in the USA is <100. What would you like your LDL to be?

My LDL is 118… I am thinking I would be better off increasing my LDL somehow.

Show Me That Reducing LDL Reduces CVD Risk or Heart Disease

Yep… find a study please because I have not found any. Heart disease is a subset of CVD and is a form of atherosclerosis: the disease of the arteries. Atherosclerosis is very dynamic.

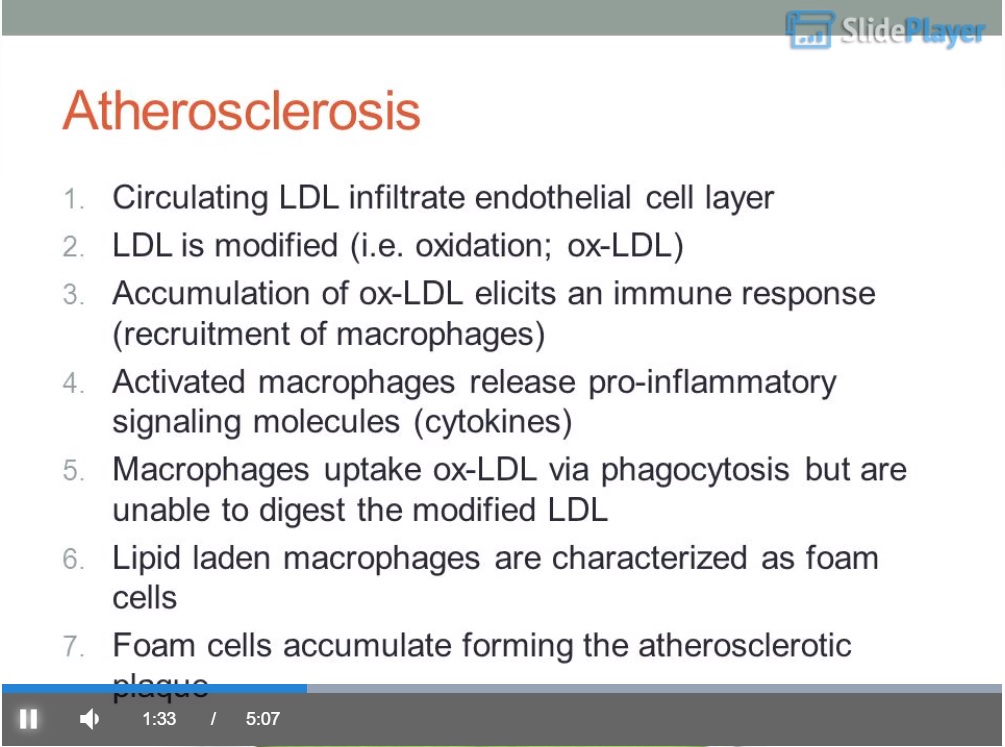

Screen capture from here.

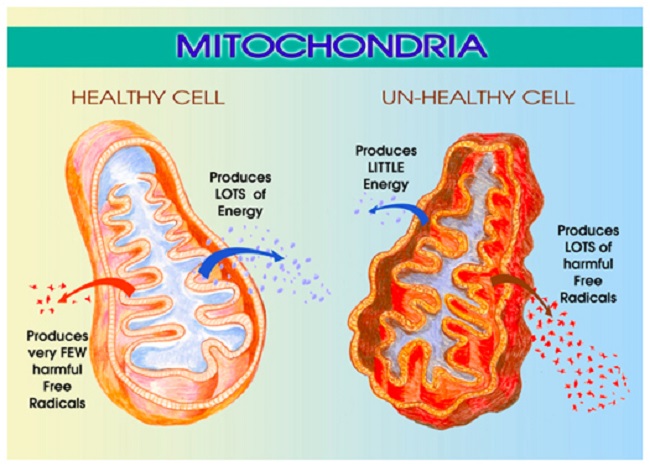

Here you can see how atherosclerosis forms: LDLs infiltrate endothelial cell layer. Endothelial cell layer is like a permeable tube inside of which is the artery. Take note of point 2: LDL is modified (i.e. oxidation; ox-LDL). In other words, something happens to the LDL as it crosses into the endothelial wall. It gets oxidized—why does it oxidize? Anyone? Hint: oxidation is a byproduct of foods that cause lots of free radicals, which may be um… I don’t know… donuts… French Fries cooked in soy, corn, or vegetable oil… alcoholic beverages… perhaps fruit juices or soda pops. So: sweeteners, excess carbs, PUFA (polyunsaturated fats), alcohol, processed foods, and alike can cause modified LDL because they all create free radicals.

Next let’s look at point 3: The accumulation of these modified LDLs initiates an immune response—why? Because they are modified, and the body no longer recognizes them as LDL. The body needs to get rid of them. The immune system unleashes a host of macrophages to eat up the modified LDL. Such immune attack is an inflammatory step, releasing pro-inflammatory signals, called cytokines. Now your body is in trouble. Macrophages are not able to clear the modified LDL; they are very sticky and have modified appearances. They build up in the endothelium, creating an inflammation—like a pimple filled with sticky substance.

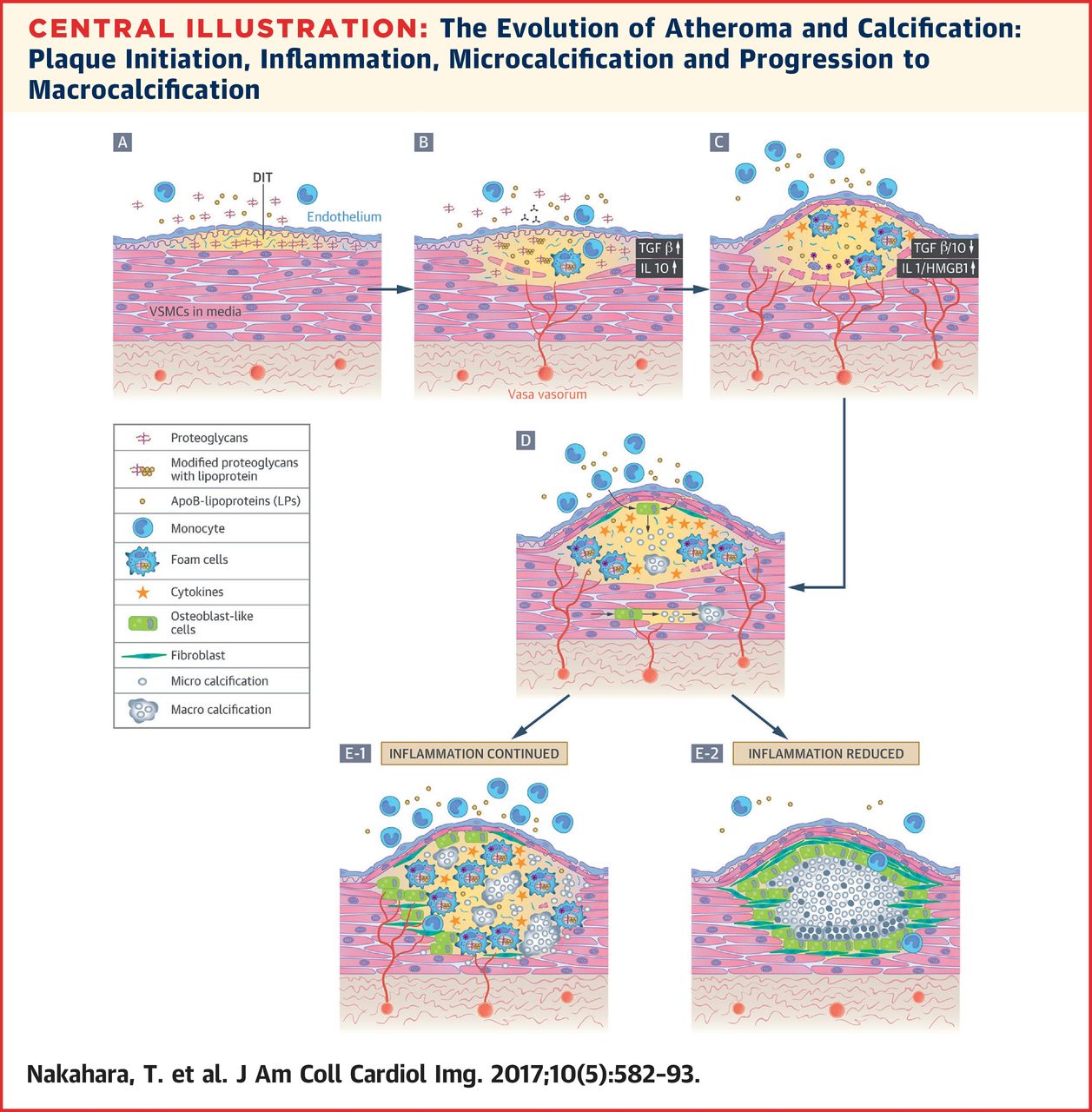

This pimple stretches the wall of the endothelium as well as it presses on the wall of the artery toward the inside of the artery, creating a bulge—narrowing the arteries—and, as the walls there are weakened, tears are more likely to appear from the accelerated speed of the blood cells (this is hypertension). What is the missing step? Calcification.

On the above image you can see the entire process step by step. Calcification—by calcium—is needed to stabilize the inflamed area so that tears are less likely. However, calcium makes that region of the artery inflexible and unable to expand as the blood pressure increases, causing a burst—i.e. clot, which causes a cardiovascular event—perhaps a fatal heart attack. Getting a CAC scan (Coronary Artery Calcium scan) can tell you where you stand in your atherosclerosis level and if you need to be concerned. If your score is high, this is the only time statins may actually help. Statins stabilize calcified atherosclerotic areas, reducing the chance for a tear and thus the formation of a clot. You should also get an NMR lipid test to check your LDL particles. The NMR test can distinguish the small oxidized LDL cholesterol particles from the large fluffy healthy ones and can set your mind at ease or make you realize that you have a problem.

Let me ask you this: if it is the type of LDL and not how much LDL one has, what are statins good for? Statins reduce the number of LDLs, but cannot change the quality of the cholesterol in LDL. What can make a difference is the kind of foods consumed. As noted earlier, foods that create a lot of free radicals cause damaged LDL particles that are very dense and are oxidized. Thus reducing LDL oxidation is the goal. Reducing sweeteners, excess carbohydrates, PUFA, alcohol, processed foods, and alike reduces the amount of free radicals, thereby reducing LDL particle damage. Modifying nutrition makes much more sense than taking statins.

In case you are considering statins, meet what you are going to be dealing with:

What Are Statins?

Statins are one of the biggest profit-making drugs for big pharma. They prevent cholesterol biosynthesis. To understand what statins really are, you need to see how they work, starting with where exactly they step into the cholesterol creating processes of the body.

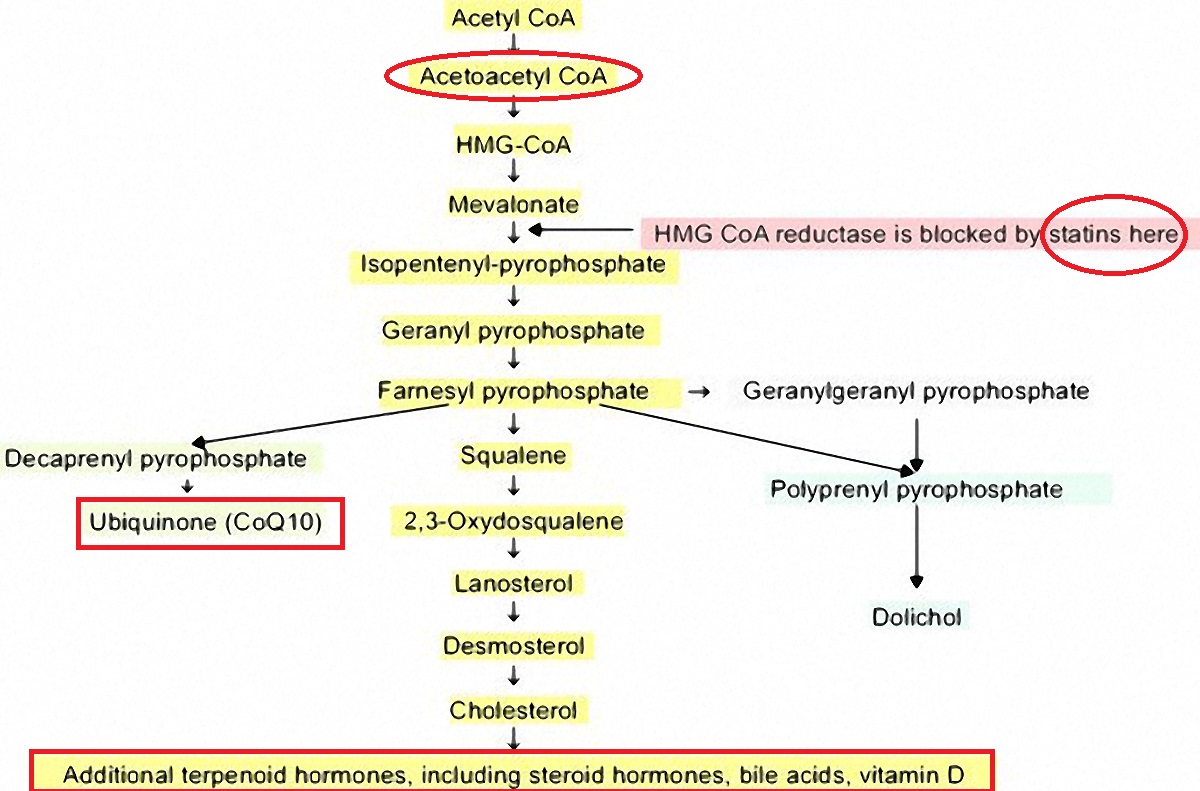

From Rosuvastatin, inflammation, C-reactive Protein, JUPITER, and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease–a perspective at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3023269/ (figure 2) (color highlights are in the original, red circles are by me)

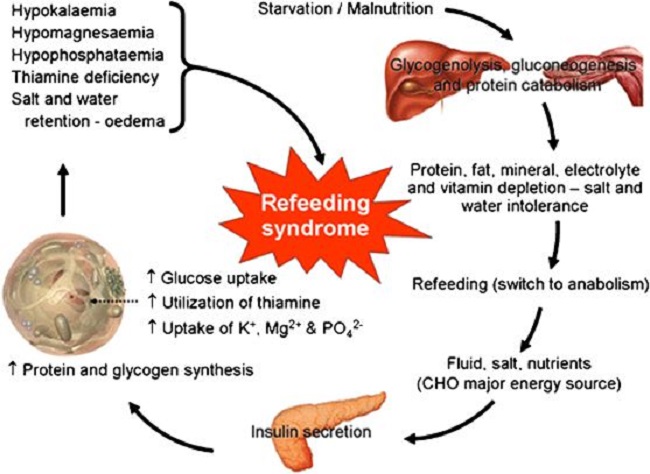

Note the areas I encircled: Acetoacetyl-CoA is the substrate used by the mitochondria to generate ATP (carbohydrates, most of protein, and fats convert to Acetyl-CoA and then to Acetoacetyl-CoA before the mitochondria can use any of it). Note that in the process of intercepting cholesterol, statins prevent all downstream steps. One of the most important elements that statins block is CoQ10.

Initially, when statins were first created, Merk seriously considered the addition of CoQ10 with every statin prescription. But that would have been admitting that statin was damaging and so they never provided CoQ10.

…patent #4,933,165 awarded to Merck & Co, in 1989, makers of lovastatin, the reasons for the combination of statin drug plus CoenzymeQ10 are as follows:

Coenzyme Q10 is a redox component in the respiratory chain and is found in all cells having mitochondria. It is thus an essential co-factor in the generation of metabolic energy and is particularly important in muscle function. Researchers, led by Dr Karl Folkers, have measured the levels of Coenzyme Q10 in endomyocardial biopsy samples taken from patients with varying stages of cardiomyopathy. These researchers observed decreasing tissue levels of CoQ10 with increasing severity of the symptoms of cardiac disease. In subsequent studies, this same research team, in a double-blind study, have reported improved cardiac output for some patients upon receiving an oral administration of CoQ10. (here)

You can find the actual patent here. Ironically CoQ10 increases heart health, so the blocking of CoQ10 by taking statins is counterproductive. Taking a statin is supposed to improve your heart health but by blocking CoQ10 actually reduces heart health. Additionally, all other hormones, including steroids, bile acids, and vitamin D production is prevented by statins.

Conclusion

While statins are said to lower cholesterol—specifically LDL—and thereby said to reduce cardiovascular risk, there has been no research proving that reducing LDL prevents cardiovascular events. As you have seen earlier, reducing LDL has negative consequences. The only true benefit of statins is the stabilization of calcified areas. If you have a lot of modified oxidized LDL particles, by reducing total LDL, you reduce the oxidized cholesterol but the healthy fluffy LDL cholesterol particles also get reduced. A far better way to achieve the desired changes is by dietary modifications. I hope you are now understanding the consequences of statins, what LDL really means, how one gets atherosclerosis, and what you should stop eating/drinking if you are concerned.

Sources

1 Meador, C. K. The Last Well Person. New England Journal of Medicine 330, 440-441, doi:10.1056/nejm199402103300618 (1994).

2 Reboul, E. & Borel, P. Proteins involved in uptake, intracellular transport and basolateral secretion of fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids by mammalian enterocytes. Progress in Lipid Research 50, 388-402, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2011.07.001 (2011).

3 Sachdeva, A. et al. Lipid levels in patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease: An analysis of 136,905 hospitalizations in Get With The Guidelines. American Heart Journal 157, 111-117.e112, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.010 (2009).

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

This image was created using Canva AI.

This article was published originally on February 14, 2019.