DES daughters have unique credentials and knowledge regarding cervical cancer. We have become cervical cancer “experts” based on our own shared experiences and through our knowledge of DES research. We also have the advantage of acquiring this knowledge about cervical cancer before HPV was even detected; and before HPV tests and HPV vaccines were developed.

We know that there are two main types of cervical cancer: the slow-developing squamous-cell cancer (squamous carcinoma); and the much more aggressive glandular-cell cancer (adenocarcinoma). We know because we are at higher risk of both types.

In retrospect the DES story is a result of serendipity, a confluence of very specific and unique circumstances. DES emerged as a public health crisis in 1971 when it was discovered that DES daughters were at risk of an aggressive, glandular cancer of the cervix/vagina because of their in utero exposure to DES.

In a strange way it was actually fortunate that the ‘DES cancer’, clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix/vagina, was so unexpected and so shocking that it was noticed by clinicians, i.e. a rare virulent cancer previously only seen in post-menopausal women was suddenly being diagnosed in young women and girls.

It was also fortuitous that these cancer cases were located in a very specific geographical region- a particular hospital, the Vincent Memorial Hospital, in Boston. The original and most influential promoters of DES as a pregnancy maintenance treatment were The Smiths of Boston: Dr George VS Smith, Head of the Gynecology Department at Harvard University Medical School from 1942 to 1967; and his wife Dr Olive Watkins Smith, a biochemist. The ‘DES Cancer’ was originally known as ‘The Boston Cancer’

In retrospect, it was also fortunate that the use of DES during pregnancy was always controversial and that clinical trials were undertaken in the early 1950s. In fact one to the earliest large-scale, prospective, double-blind, randomised clinic trials (RCT) reported in the medical literature was conducted on DES and involved 2,000 women.

As a result of these circumstances – the sentinel finding of the ‘DES Cancer’; and the existence of research cohorts that could be reassembled – there has been follow-up in the USA into the long-term adverse outcomes of DES exposure. The cohorts of these original RCTs were reassembled providing a strong research tool – DES mothers could be compared to mothers in the control group; DES daughters with the control group daughters; DES sons compared to the control group sons.

The DES Cancer: A Decades-Long Side Effect

The ‘DES Cancer’ finding sent shock waves through the medical science community. Up until this time, based on the Thalidomide tragedy, it was believed that any adverse outcomes to a drug would be evident soon after the exposure, as in “birth defects”. With DES and clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix/vagina, the adverse outcome was expressed decades after the exposure.

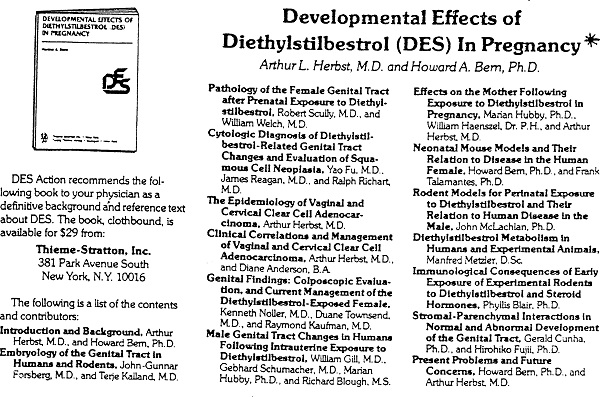

It was found that the timing of the DES exposure was critical; and, using mice, researchers were able to examine more precisely the effect of timing and dose. The mouse is a valid model as the differentiation stages of the reproductive tract is similar and comparable to that of a human. By correlating both dose and time of exposure, researchers were able to replicate in mice the adverse health outcomes found in the human DES population. A 1981 landmark publication, Developmental Effects of DES in Pregnancy edited by Arthur L. Herbst and Howard A. Bern, brought together leading experimental researchers and expert DES clinicians.

And this collaboration continued. The DES experience was central to the development of the scientific endocrine disruption paradigm. DES is the primary model for environmental endocrine disruptors.

From Lessons learned from perinatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol

“The synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES) is well documented to be a perinatal carcinogen in both humans and experimental animals. Exposure to DES during critical periods of differentiation permanently alters the programming of estrogen target tissues resulting in benign and malignant abnormalities in the reproductive tract later in life.

Using the perinatal DES-exposed rodent model, cellular and molecular mechanisms have been identified that play a role in these carcinogenic effects. Although DES is a potent estrogenic chemical, effects of low doses of the compound are being used to predict health risks of weaker environmental estrogens. Therefore, it is of particular interest that developmental exposure to very low doses of DES has been found to adversely affect fertility and to increase tumor incidence in murine reprodu ctive tract tissues. These adverse effects are seen at environmentally relevant estrogen dose levels.

New studies from our lab verify that DES effects are not unique; when numerous environmental chemicals with weak estrogenic activity are tested in the experimental neonatal mouse model, developmental exposure results in an increased incidence of benign and malignant tumors including uterine leiomyomas and adenocarcinomas that are similar to those shown following DES exposure.

Finally, growing evidence in experimental animals suggests that some adverse effects can be passed on to subsequent generations, although the mechanisms involved in these trans-generational events remain unknown.

Although the complete spectrum of risks to DES-exposed humans are uncertain at this time, the scientific community continues to learn more about cellular and molecular mechanisms by which perinatal carcinogenesis occurs.

These advances in knowledge of both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms will be significant in ultimately predicting risks to other environmental estrogens and understanding more about the role of estrogens in normal and abnormal development.”

“The ability of synthetic chemicals to alter reproductive function and health in females has been demonstrated clearly by the consequences of diethylstilbestrol (DES) use by pregnant women…. The daughters of women given treatment with DES were shown to have rare cervicovaginal cancers. Since the initial 1971 publication linking treatment of women with DES and genital tract cancers in offspring, other abnormalities have been observed as the daughters have aged, including decreased fertility and increased rates of ectopic pregnancy, increased breast cancer, and early menopause. Many of these disorders have been replicated in laboratory animals treated developmentally with DES. The lessons learned from 40 years of DES research are that the female fetus is susceptible to environmentally induced reproductive abnormalities, that gonadal organogenesis is sensitive to synthetic hormones during a critical fetal exposure window, that reproductive diseases may not appear until decades after exposures, and that many female reproductive disorders may co-occur.

Other synthetic chemicals used in commerce are known to mimic hormones and have been shown previously to contribute to disease onset. These chemicals are called endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs). Endocrine-disrupting compounds are either natural or synthetic exogenous compounds that interfere with the physiology of normal endocrine-regulated events such as reproduction and growth. Although there are many hormonal pathways through which EDCs can act (e.g., agonists or antagonists of steroidal and thyroid hormones), many of the reported EDC effects in wildlife and humans are caused through alteration of estrogen (E) signaling. This is because E signaling is evolutionarily conserved among animals and is crucial for proper ontogeny and function of multiple female reproductive organs

The purpose of this article is to establish the state of the science linking EDC exposures to female reproductive health outcomes. After introducing several topics crucial to understanding the etiology of female reproductive disorders, we present an overview of ovarian, uterine, and breast development, as well as how exposure to EDCs may contribute to some of the most prevalent reproductive disorders in these organs and to pubertal timing. Emphasis is placed on the period of development that currently is known to be most susceptible to disruption and harm by exposure to EDCs. To conclude, we present both specific research needs and several general initiatives needed to improve women’s reproductive health.”

DES Mothers and Breast Cancer

Another example of serendipity concerns the discovery that DES mothers have a higher incidence of breast cancer because of their DES exposure. When the ‘DES Cancer’ was discovered, DES Follow-up clinics were established for DES daughters to attend for the recommended special examination. The nurse in charge of one of these clinics, on chatting to the DES daughters before they had their examination, was struck by the number of daughters who were upset that their mothers had been diagnosed and/or died from breast cancer. This anecdotal observation led to research being carried out and the 1984 publication Breast cancer in mothers given diethylstilbestrol in pregnancy.

The findings were that DES mothers were 40 to 50% more likely than the control group to develop breast cancer. The authors noted a trend that the DES mothers developed the cancer at an earlier age; and that they developed a more aggressive form of the disease with a higher mortality rate.

This finding was further confirmed with animal modelling. Of course it has been known for decades that DES caused mammary cancer in experimental animals. As pointed out by Pat Cody in DES Voices: From Anger to Action (2008), animal studies dating from the 1930s showed that oestrogen administered to animals – cats; guinea pigs; monkeys; rabbits; and especially in what came to be the favoured mammals, mice and rats – showed reproductive tract malformations and cancer.

DES was synthesised in 1938 by a team of scientists in England, headed by Sir Charles Dodds. Later in 1938 Dodds reported that orally active oestrogen, including DES, interrupted early pregnancies in rabbits and rats. In 1938, a French researcher reported that male mice treated with DES developed breast cancer.[Lacassagne A (1938) Apparition d’adenocarcinoma mammaires chez des souris males traitees par une substance oestrogene synthetic. Comptes Rendus Biol. (Paris) 129.]

As explained in Barbara Seaman’s highly recommended book The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth (2003), Dodds was aware of what a powerful and potentially carcinogenic drug he had synthesised. In the months following the discovery Dodds became increasingly concerned about the carcinogenicity of the newly synthesised drug. In his laboratory he noticed that men on his staff who handled the stilboestrol powder were growing breasts, suggesting to him stilboestrol might cause breast cancer in men. He suggested that animal studies be carried out looking at the carcinogenicity of stilboestrol in male rodents. In 1940 a paper was published showing that stilboestrol caused mammary cancers in both male and female mice.

DES: Not One but Two Cervical Cancers

That DES daughters also had a higher incidence of squamous-cell abnormalities (when compared to the control group) was recognised quite early on. At the same time it was reported that DES daughters suffered much higher rates of cervical stenosis following minor procedures.

In the early years many of us purchased medical dictionaries and headed off to medical libraries to look at source material. DES Action has always strived to make information contained in medical journal articles accessible to our members. We have a long history of sharing information, reviewing journal articles and explaining terminology, thus empowering members to make informed decisions about their health care. The issue of how to treat dysplasia was featured in our newsletter DESPATCH a number of times. For example, DESPATCH No. 9 November 1982, looked at dysplasia treatment options and cervical stenosis, and explained the terminology.

I think our introduction to this edition of DESPATCH is worth repeating:

“The actual changes that DES exposure causes are quite complex. As a result of this, a DES daughter not only has to cope with the actual screening examination, but with an entirely new language.

This issue of DESPATCH is rather dry and technical: We concentrate on defining terms and de-mystifying the jargon. However, it is important that you are not intimidated by the jargon. Remember a true expert will not hide behind jargon but will be able to explain things simply and clearly. So, if you don’t understand what the doctor is saying, say so and ask that it be explained again….and again!”

It was hypothesised that the DES-related structural changes in both the cervix and uterus may be associated with connective tissue alterations that predispose to abnormal healing and increased propensity to cervical stenosis. Therefore the recommended management of DES daughters with these squamous-cell abnormalities was monitoring with minimal intervention. Those of us who knew we were DES exposed, and were attending DES follow-up screening clinics, were in the privileged position of having expert monitoring without intervention. And that is why many DES daughters have personal experience of even high-grade squamous-cell abnormalities resolving over time without any treatment.

That’s not to say it was easy, particularly in the early years. Often we were being called back for 3 monthly checks. But as time passed, and we experienced that the abnormalities ‘matured’ or resolved, we became more relaxed about squamous-cell abnormalities.

We used to joke that discussing cervix status seemed to be almost a defining feature of our group – nowhere else you could comfortably talk about the state of your cervix.

As I said we were in a privileged position of having expert screening with clinicians who explained and discussed issues. Over the years I’ve had three occasions when the clinician noted that “according to the textbook” he should probably do a biopsy but, as he was confident it would resolve, he would leave it. As I knew he was an expert, and that he was referring to squamous-cell abnormalities, I was happy to go along with this suggestion.

Of course lurking in the background was the knowledge that we have a life-long risk of the ‘DES Cancer’, clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix/vagina. Initially we were screened every 6 months, but then it went to annual checkups.

DES Daughters and the HPV Vaccine

So when there was news of a ‘cervical cancer vaccine’ being developed, we naturally were very interested and read up on it. However, the more we read, the less sense it made. When we realised it was for squamous-cell cervical cancer, the unanimous opinion was “Why bother?!’ It wasn’t even a cervical cancer vaccine, but a HPV vaccine (or, to be pedantic, a ‘HPV strains 16 and 18’ vaccine).

Why would you bother having a part-HPV vaccine when we knew through experience that even high-grade squamous-cell abnormalities usually resolved spontaneously without any intervention?

The vaccine was designed to prevent the very abnormalities that empirical evidence of the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) showed would resolve anyway – crazy. We looked on in bemusement at the HPV hysteria that erupted in 2006. It was an extraordinary example of manipulating the media for commercial gain when the drug manufacturer orchestrated the listing of Gardasil on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and the National Immunisaton Program.

This battle to list the HPV vaccines, and how commercial pressure and political opportunism threatened the independence of Australia’s healthcare system, is discussed in Healthcare’s Sticking Point.

It was a classic textbook example of disease mongering: Take a common, essentially benign condition (HPV infection) and it suddenly and only becomes “serious” or “life-threatening” when Big Pharma has a product to sell (i.e. HPV vaccine).

It was disgraceful that public health money was diverted into the HPV industry. In terms of women’s health, it would have been more productively spent on education programs and publicity campaigns on the value of Pap smears, in order to raise the participation rate of the NCSP; or on research into a screening test for ovarian cancer.

All we could do was shake our heads in bewilderment: If the government wanted to waste billions of dollars on a school-based vaccine program of unproven value, so be it. At least there was the safety net of the NCSP and women having regular Pap smears.

And now that is under threat. The proposed changes to the NCSP, due to be implemented on 1 December 2017, is that HPV testing has been fast-tracked to become the primary cervical screening tool; that the commencement age be raised to 25 years; and the screening interval be extended to 5-yearly.

This is a public health crisis in the making. There are two type of cervical cancer and the proposed policy is focused on just one. It is modeled exclusively on squamous cancer and ignores empirical evidence from the NCSP that glandular cancer now represents approximately 30% of cervical cancers diagnosed in Australia today.

This will put the lives of women, particularly young women, at risk.

As there appears to be a push worldwide to introduce this screening regimen (HPV testing as the primary cervical screening tool; commencement age 25 years or later; and 5-yearly screening intervals) potentially millions of women are at risk. It could be a medical and public health disaster on a scale never before seen.

If the DES experience teaches us anything, it is to remain vigilant about the efficacy and safety (both short-term and long-term) of pharmaceutical products, and this includes vaccines. It involves understanding the different types of cervical cancer; understanding the various risk factors, including HPV and endocrine disruptors; and being informed about the benefits and limitations of the screening tests, such as the Pap smear and the HPV test.

Stay with us, as we cover each of these topics over the next few weeks.

DES Daughters, Sons, and Grandchildren – Share Your Story

If you are the daughter, son or grandchild of a woman given DES during pregnancy, please share your story with us.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

This article was published originally on May 1, 2017.

Photo by Ernest Karchmit on Unsplash.