Here you can read a small and slightly modified section from my upcoming book “Fighting the Migraine Epidemic: A Complete Guide. How to Treat & Prevent Migraines Without Medicines.” This is the 2nd edition of my book that thousands of migraineurs have used for years. The excerpt here explains what stress is in terms of the body, how it is connected to hormones, and why it may end up as a migraine for those who have what I call a migraine-brain. Migraine-brain is anatomically and physiologically very different from a non-migraine brain and this difference gives rise to the possibility of a trigger, causing a migraine.

Listing triggers is one thing; understanding them and explaining how they initiate a migraine is much more difficult—this is just a taste of the full explanation found in the book.

Stress in Biology

Stress is probably one of the most common words in our everyday use. By stress we normally mean something that makes us busy, angry, we find irritating, or we simply feel under duress, or even extremely happy for the moment. Here is well-accepted definition of stress in biology:

“…a person’s response to a stressor such as an environmental condition or a stimulus. Stress is a body’s method of reacting to a challenge… Stress typically describes a negative condition or a positive condition that can have an impact on a person’s mental and physical well-being” (quote).

The body’s reaction to the negative or positive environmental stimulus takes place by the activation of the autonomic (unconscious) nervous system via biochemical processes. This was a mouthful, so let’s take it apart: environmental stress on the body initiates internal chemical processes, these in turn activate systems in the body that are not under conscious control, such as anxiety, fight-or-flight, IBS, RLS, heartbeat, heavy breathing, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, etc. Stress need not be negative. Positive environmental influences can just as much affect our stress response. For example, extreme happiness about getting an A on a test in a hard subject, ending up with a sunny warm day when the forecast predicted cold and gloomy weather on vacation, getting a new job, getting engaged or married, all can bring on a euphoric high, causing a hormonal changes that results in a migraine. Such a stressor is also one of the reasons why laughing strongly we may find ourselves crying. Thus, a stressor can both come from positive and negative stimulus. Both can cause stress on the body, and change many hormones that, in the case of a migraineur, can disrupt electrolytes, and thereby, cause a migraine.

Stressors, Cakes, and Migraines

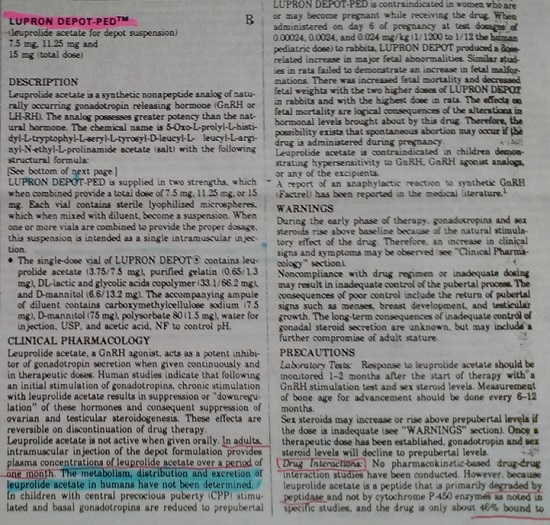

Many people respond to stress by craving sweets. Eating a piece of cake at a wedding or birthday makes one feel good because it releases dopamine in the brain (1, 2). This can cause many undesirable after-effects such as hunger, shakiness, sugar crash (reactive hypoglycemia), as well as a migraine. Thus, while eating sweets is a customary celebration of life events and a happy end to dining out or watching a favorite movie, for migraineurs it is a major stressor. The reason is that migraineurs are glucose sensitive (3-7). To show the problem, I grab a quote from my medical manual:

“…serum Na+ [sodium] falls by 1.4 mM for every 100-mg/dL increase in glucose, due to glucose-induced H2O [water] efflux [exit] from cells” (8)

While a 100-mg/dL increase in blood glucose seems unrealistic—after all the guideline is that the healthy blood glucose level is between 70 and 140 at all times, but for those who are glucose sensitive, the increase can be significantly higher. I am a migraineur (and therefore, glucose sensitive) and have tested this on myself. I don’t eat sugar so I ate 20 cherries instead. The amount of glucose in the 20 cherries is miniscule compared to a slice of cake, 21 carb grams, of which only 10 grams is glucose: 2.5 teaspoons of pure glucose. The human body’s entire blood supply only contains 1 teaspoon of sugar, by eating 20 cherries I more than tripled the amount. This showed up as a near 100-point increase in my glucose 30 minutes after I finished the cherries. Before you give a thought to insulin resistance in my case: don’t. My blood sugar returned to normal in about one hour. Glucose sensitivity is neither diabetes nor insulin resistance, but it represents a glucose regulation genetic variance. So you can see that by eating a piece of cake, a major electrolyte problem will follow (both sodium and water leave the cells), especially for those with glucose sensitivity.

In the book, I thoroughly discuss electrolyte disruption. Here, I refer you to an article in which I summarized some of the genetic variances associated with migraineurs being so sensitive to the dysregulation of their electrolytes—particularly by the loss of sodium.

Can Stress Disrupt Electrolytes?

For a very long time I’ve heard people say that stress brings on headaches, but not migraines—this is not true. Our nervous system translates external stress and transmits it to relevant internal organs, tissues, and cells via hormones. In response to this hormonal change, the affected cells change their biochemistry. This internal biochemical change is the stress response to the external stress events and conditions. Just as there are internal stressors, such as the menstrual cycle or a tummy bug, that can change the body’s chemistry, so can external stressors create biochemical imbalances and disturb hormonal processes. To help you distinguish very clearly between external and internal stressors, here are three short examples with connection to a chain-reaction of effects:

External stressor: a migraineur driver gets stressed out about the traffic-jam on the freeway. This causes her adrenaline, steroid, cortisol, and other stress hormones to increase, blood pressure to rise, and her heart to pump faster and stronger, creating a potential for heart attack or stroke. In this case, an external factor directly caused the internal stress on the vascular system.

Internal stressor: the increase in our driver’s blood pressure causes extra stress on her arteries. This alone can cause trouble for the vascular system but let’s continue to the brain. This extra stress calls on the brain and its neurotransmitter activities to use energy for satisfying the higher demands of brain regions reacting to the external situation, and being involved in the preparations for a possible response to it. This unplanned, extra physiological activity may force the neurons in the driver’s brain to work at a pace that is above what she is prepared for—her threshold—while she is simply sitting in her car. Increased energy levels are needed, but as she is fuming over the traffic jam, she is not providing any extra energy (e.g., food) to address the deficit. During this unexpected energy expenditure – this internal stress – the body must suddenly work harder without any increase in nutrition and hydration. If not mitigated, this will lead to a biochemical imbalance, i.e. electrolyte disturbance. So even if the external conditions have not directly caused a life threatening, vascular reaction, that is, she was not hit by a stroke or a heart attack, the stress may still end up giving her a migraine.

This is not a good situation for anyone; even non-migraineurs often come down with a stress headache. Furthermore, some of these hormones use insulin receptors, thereby leaving few insulin receptors free to pick up glucose, reducing the speed with which blood glucose can be delivered to cells by insulin. The longer glucose stays in the blood, the unhealthier it is. Having lots of glucose in the blood for a long time is biologically equivalent to insulin resistance. Since all insulin receptors are taken up by steroid hormones, the brain is not receiving glucose, so it requests the liver to release glucose—the liver retains a supply of glycogen for this reason. However, receiving more glucose (from the liver) into the blood when the insulin receptors are still occupied by steroid hormones just increases the level of glucose in the blood, while the brain continues to starve.

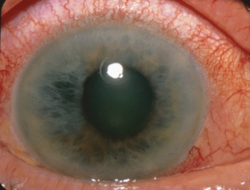

Stress on the Brain: a neuron is stimulated by the unpleasantness of the traffic. The neuron’s message is transferred to another neuron by the neurotransmitters it passes into their shared synapse. Since the migraine brain is endowed with more sensory receptor connections than normal, whatever neurotransmitters a sensory neuron releases, more receptors will pick them up with the effect of amplifying the signal. This is why migraineurs are “hyper sensitive” to odors, sounds, etc. The migraineurs’ hyper sensitive brain amplifies everything sensory.

The Migraine

How does this become a migraine? The answer is quite simple. If we stimulate a single neuron and no other neuron pays attention (as in a non-migraine brain), all the effort of that neuron is inhibited, the fire is put out, and no energy is used. When a migraine brain is stimulated, the activation of the neurons with many more receptor connections pass the signals to more neurons—the signal will be amplified. More stimulation results in alarm level reactions. The release of the extra neurotransmitters uses more energy; a migraine-brain uses much more energy than the brain of a non-migraineur. Using more energy means the brain needs to take in more energy. The kind of energy needed is for action potential generation, which requires salt (sodium chloride) and not glucose. Unfortunately, if the migraineur doesn’t recognize the need for salt, sugar cravings will follow! The more sweets are eaten, the more sodium and water is lost from the cells and the more trouble the migraineur gets into. Without eating salt, the region deficient in energy will stop producing action potential and will go off-line. Neuron regions that went offline and cannot create action potential are said to experience cortical depression, which initiates cortical spreading depression (watch the video to see how it moves), which is a wave of voltage from unaffected parts of the brain, that can reach the pain sensory nerves in the meninges. Migraine pain is on its way!

Having pain when something is not working right is an evolutionary advantage, but in the case of migraineurs, the sensitivity is in overdrive. Migraine management and prevention requires quick actions and very serious maintenance of the electrolyte homeostasis. Because of the hyper sensory sensitivity of the migraine brain, the electrolyte minerals for a migraineur need to be in different density from that of a non-migraineur. In conclusion: stress is a migraine trigger.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Additional Sources:

- Rada P, Avena NM, & Hoebel BG (2005) Daily bingeing on sugar repeatedly releases dopamine in the accumbens shell. Neuroscience 134(3):737-744.

- Avena NM, Rada P, & Hoebel BG (2008) Evidence for sugar addiction: Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 32(1):20-39.

- Mohammad SS, Coman D, & Calvert S (2014) Glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome and hemiplegic migraines as a dominant presenting clinical feature. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 50(12):1025-1026.

- Gruber H-J, et al. (2010) Hyperinsulinaemia in migraineurs is associated with nitric oxide stress. Cephalalgia 30(5):593-598.

- Kokavec A & Crebbin SJ (2010) Sugar alters the level of serum insulin and plasma glucose and the serum cortisol:DHEAS ratio in female migraine sufferers. Appetite 55(3):582-588.

- Dexter JD, Roberts J, & Byer JA (1978) The Five Hour Glucose Tolerance Test and Effect of Low Sucrose Diet in Migraine. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 18(2):91-94.

- Shaw SW, Johnson RH, & Keogh HJ (1977) Metabolic changes during glucose tolerance tests in migraine attacks. J Neurol Sci 33(1-2):51-59.

- Longo DL, et al. (2013) Harrison’s Manual of Medicine 18th Edition (McGraw Hill Medical, New York).

Image by Pedro Figueras from Pixabay.

This article was published originally on July 10, 2017.