Why Publish Another Case?

Just last week, we published a case of classic beriberi in a 23 year old man, and now, yet another case comes to our attention. Most in the medical profession are under the false impression that beriberi, thiamine deficiency, has been eradicated in Western cultures. It has not. In fact, a number of factors in modern Western culture have aligned to make thiamine sufficiency more precarious than ever. High calorie malnutrition and toxicant exposures are top among them. For a detailed look at thiamine deficiency in modern cultures, see our new book: Thiamine Deficiency Disease, Dysautonomia, and High Calorie Malnutrition.

Kaleidoscope of Symptoms Associated with Thiamine Deficiency

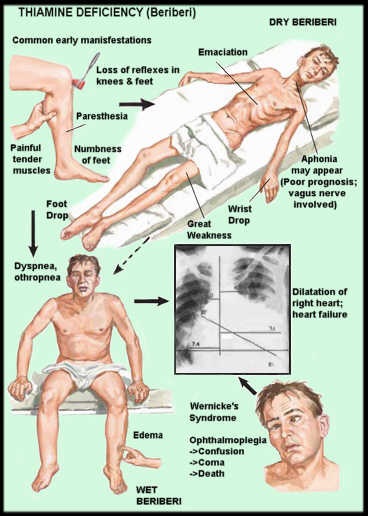

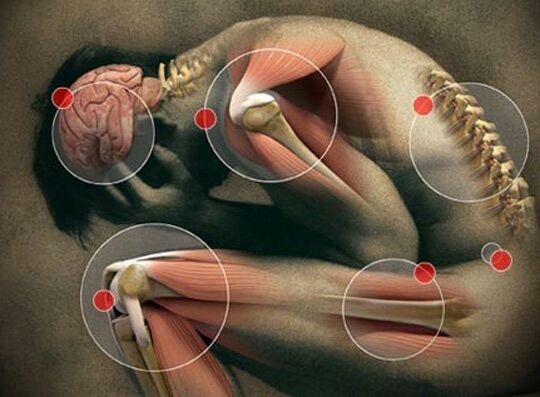

There are a colossal number of symptoms associated with thiamine deficiency. The symptoms are confusing and not being seen for what they represent. First of all, let me make it clear: we are oxygen consuming animals and anything that interferes with oxygen utilization in the body will produce symptoms that are called to our attention by the brain and demand explanation. Any adverse sensation whether it be pain, itching or any other symptom is expressly a result of brain action. Joint pains are not perceived in the joints. They are perceived in the brain, even though the joint is actually the location of the inflammation.

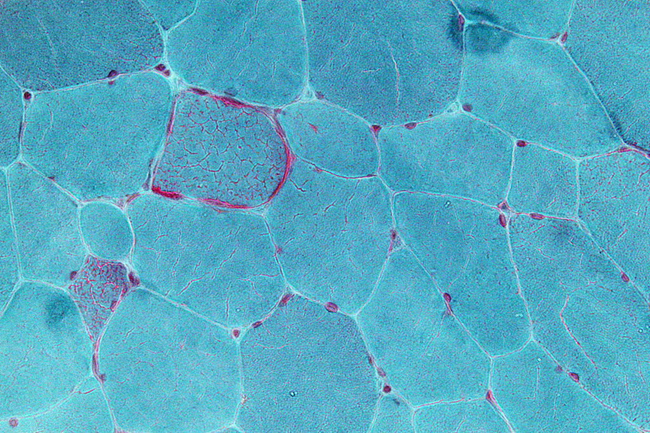

The body consists of 70 to 100 trillion cells, all of which have to cooperate in producing human function. Each of these cells requires energy that is developed in specialized organelles within each cell. These organelles are called mitochondria and the way that they produce the required energy is by the combination of oxygen with glucose. Known as oxidation, thiamine is a major catalyst in this process and can be compared to a spark plug in a car cylinder. No gasoline (glucose), no function. No oxygen, no function. No spark plug (thiamine), no function. If oxidation in the mitochondria is compromised, the function of the cell in which they reside is also compromised. Because the brain and heart are the highest oxygen consuming organs in the body, it is not particularly surprising that these organs are the most affected in the disease called beriberi.

Please remember that this is an extremely ancient disease for which no cause was known for centuries. The word beriberi, according to the Oxford English dictionary, comes from a Sinhalese phrase meaning “weak, weak” or “I cannot, I cannot”, the word being duplicated for emphasis. I think of the body as being like an orchestra. Every organ knows exactly what it has to do, but its action must be monitored by the brain which acts as the conductor in playing “the Symphony of Health”.

A Case of Unrecognized Beriberi

The woman whose symptoms are discussed here is 38 years of age. During childhood she experienced what she called a great deal of pain, repeated episodes of candida infection (yeast) breathing trouble with swimming and running, reactive hypoglycemia, chest pain, panic attacks and nausea. She has recently experienced dizziness.

How Was She Treated?

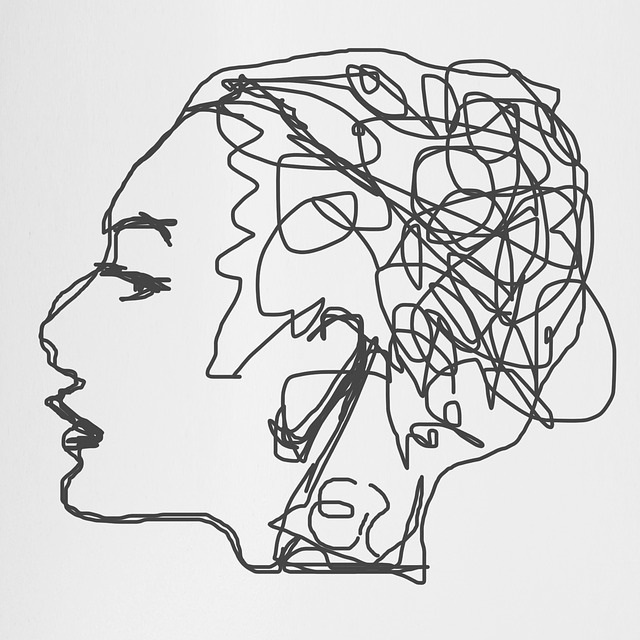

Because the many physicians that she has seen were unable to find significant laboratory changes, the symptoms were usually explained as “it is all in your head”. This is really a pejorative diagnosis because it is assuming that the unfortunate patient is either inventing the symptoms or experiencing them in her imagination. The paradox is that the symptoms are produced in the brain by abnormal signals between the brain and body organs. They are just as real as any other symptom where there is physical evidence of its cause.

Modern medicine seems to think in extraordinarily limited terms and prednisone is offered for many different symptoms as it was in this case. Prednisone made her symptoms worse as indeed it often does. Dizziness was treated by a chiropractor by an “adjustment of the Atlas” (the first bone in the neck that supports the skull) and made her worse. She was found to have scoliosis of the spine and without going into details, this is because of compromised oxidation in the brainstem. It results in asymmetric motor signals to the muscles on either side of the spine, producing the typical curvature.

Understanding the Clinical Clues

The symptoms in childhood indicated even then oxidation was inefficient.

Difficulty breathing. She had breathing trouble when swimming or running, indicating that the breathing control mechanisms in the brain were affected.

Reactive hypoglycemia. She consumed a great deal of sugar and reported reactive hypoglycemia, a classical effect of thiamine deficiency caused by the excessive sugar. It results in overproduction of insulin, hence the drop in blood sugar.

Digestive problems. She reported “stomach problems” in pregnancy, gastritis and GERD, all of which can occur with thiamine deficiency.

Panic attacks. Chest pain, panic attacks and nausea are all related to brain oxygen compromise.

Nystagmus. Her dizziness, reported to be associated with “vertical downbeat nystagmus” are both typical of beriberi.

Yeast infections and Brewer syndrome. She had repeated episodes of yeast infection. This is an opportunist organism, meaning that it is detecting a body situation which is favorable to it and not to its host. Of course, yeast is used to create alcohol from sugar and the squeaks and bubbles experienced by the patient represent the effects of ongoing fermentation in the bowel. So her complaint of “constantly feeling drunk” is quite real and is known as the Brewer syndrome.

Connecting the Dots: The Myriad Manifestations of Thiamine Deficiency

The history in this woman indicates that her health problems existed in childhood and may well have started because of her mother’s pregnancy. She indicated that she consumed a great deal of sugar, by far and away the easiest way to produce thiamine deficiency. The nystagmus and dizziness are manifestations of oxidative dysfunction in the brain and indicate the ongoing problem. There may well be a genetic mechanism involved. However, the genetic mechanism can be mild enough not to result in symptoms unless nutrition and stress events are involved. She reported that she had experienced a number of surgical interferences, each one of which may have been sufficient stress to initiate downgrading in her thiamine deficiency. We now know that a marginal deficiency can be converted into full-blown deficiency as a result of the energy consumption required in meeting the stress.

We Need Your Help

Hormones Matter needs funding now. Our research funding was cut recently and because of our commitment to independent health research and journalism unbiased by commercial interests we allow minimal advertising on the site. That means all funding must come from you, our readers. Don’t let Hormones Matter die.