Over the last several months Dr. Lonsdale and I have been working on a book about thiamine deficiency and dysautonomia. Last week I wrote about the presumed connection between the Zika virus and microcephaly where I hinted at a thiamine connection. One might say, that I have thiamine on the brain and that would be a fair assumption. The old adage, ‘if one has a hammer, everything becomes a nail‘, may apply. I may be focusing too much on thiamine and its role on mitochondrial health. Alternatively, it could be that thiamine is just that important. After all, it sits atop at least two of the four energy producing pathways that give us ATP and is deeply embedded within the remainder of the oxidation process. The consequences of impaired oxidative metabolism in the brain are vast and include a range of disease processes like Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gerhig’s disease), Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, alcoholic brain disease, and stroke. Without thiamine, the mitochondrial factories stop producing energy or ATP and without ATP, stuff slows and then dies. So yes, thiamine is critical to health.

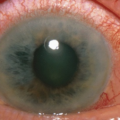

It is not difficult to imagine what happens to energy levels when thiamine concentrations diminish even slightly in an adult. An unrelenting fatigue is one of the early symptoms of struggling mitochondria and thiamine deficiency. More fundamentally, however, all the organs tasked with maintaining life, demand energy. When energy stores diminish, those organ systems struggle. The organ systems requiring the most energy, like the brain and the heart, are hit hardest. Maintain a slight deficiency chronically and damage ensues. In Cuba, for example, trade embargo policies resulted widespread thiamine deficiency in the population, which in turn initiated an epidemic of neuropathy – nerve damage. Over 50,000 Cubans were reported to have developed optic neuropathy, deafness, myelopathy, and sensory neuropathy related to embargo imposed dietary changes. In contrast to the more insidious damage initiated by chronically low thiamine concentrations, severe and acute thiamine deficiency is life-threatening, especially in children, but also in pregnant women.

With low maternal thiamine concentrations, the effects on fetal development, especially fetal brain development that requires enormous amounts of energy, are likely to be devastating. And indeed, they are. But we don’t study that very often, even in rats. Do a search on the subject and there is not much research out there. Sure, some researchers have investigated maternal thiamine deficiency in fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), postulating thiamine might be the mechanism by which FAS develops, but that is about it. Given how critical it is to fetal development, I expected more research.

It is not just alcoholics who are at risk of thiamine deficiency. An increasing percentage of Western populations are likely thiamine deficient. Thiamine depletion occurs with numerous medications and vaccines via multiple mechanisms, many of which are just beginning to be understood. Conventional farming practices use herbicides and pesticides that block vitamin B absorption and so even diets presumed healthy may not be as nutrient dense as in the past. Poor absorption from altered gut microbiomes may be another common mechanism for thiamine deficiency and emerging evidence finds that Type 1 and Type 2 diabetics excrete significantly more thiamine than non diabetics, making them thiamine deficient as well. Not studying this more broadly is leaving millions of folks to suffer with entirely preventable disease processes. During pregnancy, however, this lack of recognition and research is just downright negligent, especially when we consider fetal brain development.

Thiamine During Pregnancy

Thiamine is absolutely critical for both maternal health and fetal development. Women with hyperemesis gravidarum, excessive vomiting during pregnancy, are at a particularly high risk for thiamine deficiency and though there is increasing awareness of maternal Wernicke’s encephalopathy during pregnancy, a condition typically associated with thiamine deficient alcoholics, the full scope of damage associated with maternal thiamine deficiency is insufficiently understood. There is little to no appreciation of the long term effects on maternal health and even less recognition of how the deficiency impacts fetal development in either the short or long term.

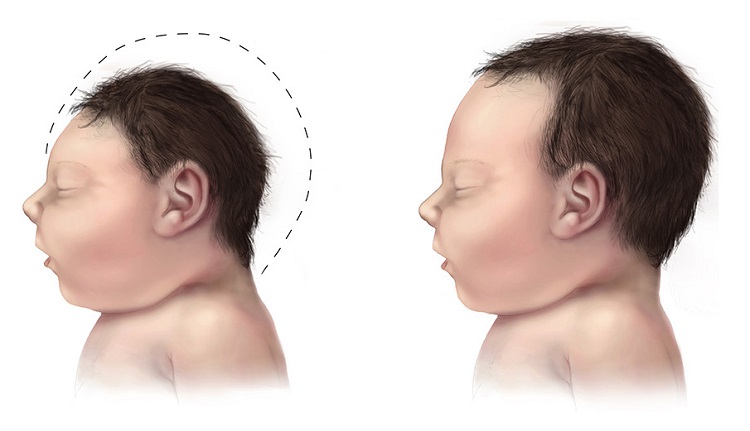

Provided mom survives a thiamine deficient pregnancy, what happens to the growing fetus? In 37% of the cases of severe maternal thiamine deficiency, spontaneous fetal loss occurs. If thiamine is critical for mitochondrial energy production, and fetal development requires exorbitant amounts of mitochondrial energy, what happens if one of the key components to that energy production process is lacking? All sorts of things, it turns out, including microcephaly. Beyond a rare congenital defect in thiamine transport believed to affect only consanguineous Amish, there are very few studies that have considered the effects of epigenetic and more functional maternal or fetal thiamine deficits. We know from the Amish cases, that when the fetal thiamine transporters are impaired, microcephaly ensues. Is it so hard to imagine that we might impair those transporters epigenetically or reduce maternal thiamine concentrations functionally by dietary choices, medications or environmental toxicants that leach nutrients and/or by malabsorption? And yet, as I dig into this, I find only a few studies that have addressed maternal thiamine and fetal brain development. Here they are.

Maternal Thiamine Deficiency and Fetal Brain Damage

A 2005 study from researchers in West Africa showed that the pups from thiamine deficient dams, had significantly smaller brains by weight. Digging deeper, they found far fewer neurons in the hippocampus, the region of the brain responsible for memory consolidation and retrieval, than the pups from thiamine sufficient diets. Brain damage in the offspring could be induced by maternal thiamine deficiency either leading up to, during, or after pregnancy (while lactating) but varied in scope, severity, and pattern. The most significant damage occurred when the dams were deficient during pregnancy.

In the offspring from perinatal thiamine deficiency, hippocampal volume was reduced by almost a third due to neural cell death. The neurons that survived were smaller than normal and misshapen. The hippocampus is critical to memory. Hippocampal damage in human adults causes all manner of amnesias and aphasias (speaking and language comprehension deficits) and is found in neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease.

The neurons affected most by the thiamine deficiency, the CA1 neurons, are especially susceptible to oxidative damage and insult. Thiamine is integral to brain oxidation and so this makes sense. What we have to remember though, is that in a fully developed human brain, oxidative damage to the CA1 region is associated with hippocampal ischemia, limbic encephalitis, status epilepticus, and transient global amnesia – very serious conditions. To a developing brain, requiring vast amounts of energy to grow, the consequences of hippocampal deficits are largely under-recognized except again in fetal alcohol syndrome.

Another animal study looked at the effects of maternal thiamine deficiency to the cerebellum of the offspring. The cerebellum is the region of the brain responsible for balance and coordinated motor movements. Here again, the damage was severe with a significant reduction of size, loss of neuron viability, and conduction. There have been a smattering of studies across the decades (here, and here, for example) looking at thiamine deficiency and brain damage in non-pregnant rats, but that’s about it.

Not much else is out there.

From these few animal studies, the work on Amish microcephaly and the work connecting neurodegenerative disorders to thiamine deficiency, we can surmise that thiamine is essential to brain development. More specifically, in pregnancies where thiamine concentrations are low, cerebral development of the offspring will be impaired in some pretty significant ways. Namely, the number and size of neurons is reduced, and as a consequent, total brain volume is reduced. If the deficiency is severe enough, microcephaly is possible and has been identified in the two of studies mentioned above. I think this is what is happening in Brazil. That is, a combination of seemingly unrelated factors, coalesce to produce fetal thiamine deficiency which results in microcephaly and other sorts of brain damage. The questions that remain include:

- By what mechanisms specifically is thiamine deficiency produced?

- What are the risks for maternal thiamine deficiency in other regions?

One of the most direct routes to thiamine deficiency during pregnancy is hyperemesis gravidarum, excessive vomiting. Case studies abound where it is often not recognized until the mother is in critical condition. It is considered a rare complication, but is it? Unless and until those questions are answered more fully and physicians recognize maternal thiamine deficiency as a potential problem, women and children will continue to be at risk for what are entirely preventable complications of pregnancy.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Image credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This article was first published on June 16, 2016.