Do you have type 2 diabetes (T2D)? How about prediabetes? OK… how about insulin resistance (IR)? No? Are you sure? I am not sure at all! Not, based on the many cases I evaluate daily. Here I present you with one case study that is not from the US or Canada. The reason why I picked one that is not from North America is because if you live in North America, more often than not your T2D or IR is not discovered by conventional blood glucose testing. This article will demonstrate the problem.

Why You Don’t Know that You Have T2D or IR

For simplicity, I will use the term T2D to represent all levels of metabolic syndrome: type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, and insulin resistance. According to the CDC, the total diagnosed T2D in age groups of 18 to 65 was around 12% of the US population (table 1) in 2017, though in 2015 the diabetes and prediabetes population was estimated at 56.1% (table 3), meaning the undiagnosed with T2D is 34% of the population, nearly three times that of the diagnosed. Currently, there 132,000 children under the age 18 assumed to have T2D but remain undiagnosed. Of the US population, about 5% of the people (of all ages) are estimated to have type 1 diabetes, which is either a genetic condition, an autoimmune disease, or in some cases may be viral—this is not yet well understood. The 5% is about double that of 2015. It is interesting to note that type 1 diabetes is also on the rise both for children and also for people with LADA (latent onset type 1 diabetes). In this paper, I only focus on T2D, what causes T2D and the reasons that so many of us remain undiagnosed. In the case study presented here, the patient permitted me to use her blood test results.

Undiagnosed T2D: A Case Study

I am fortunate to be able to work with thousands of migraine sufferers, many of whom bring their friends and family to my migraine groups even though they may not have migraines. This case study is about such a person, whom I will call now Nicole (not her real name).

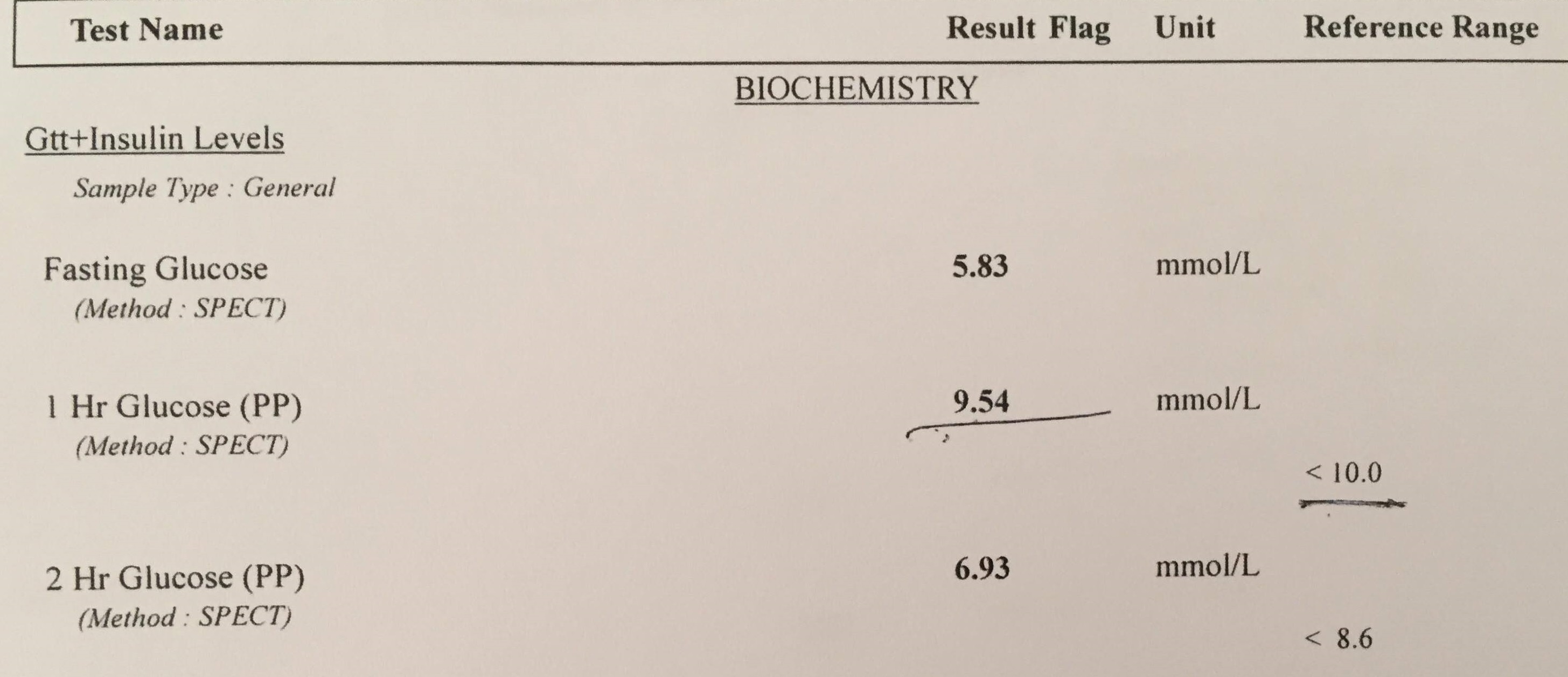

Nicole joined my migraine group because she has a relative with migraines and she had her own health conditions. I have a questionnaire that each new member fills out, and the answers are sent to me by FB private messaging. Nicole went to her doctor and received her blood test. It was an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), in which they first test a fasting measure, then she drinks 75 gr glucose, and 1 hour and 2 hours after finishing the glucose drink her blood is tested again. Here are her blood glucose test results:

Since she is from a county where they use metric, on her test you see metric blood glucose results. Here are the results in US standard:

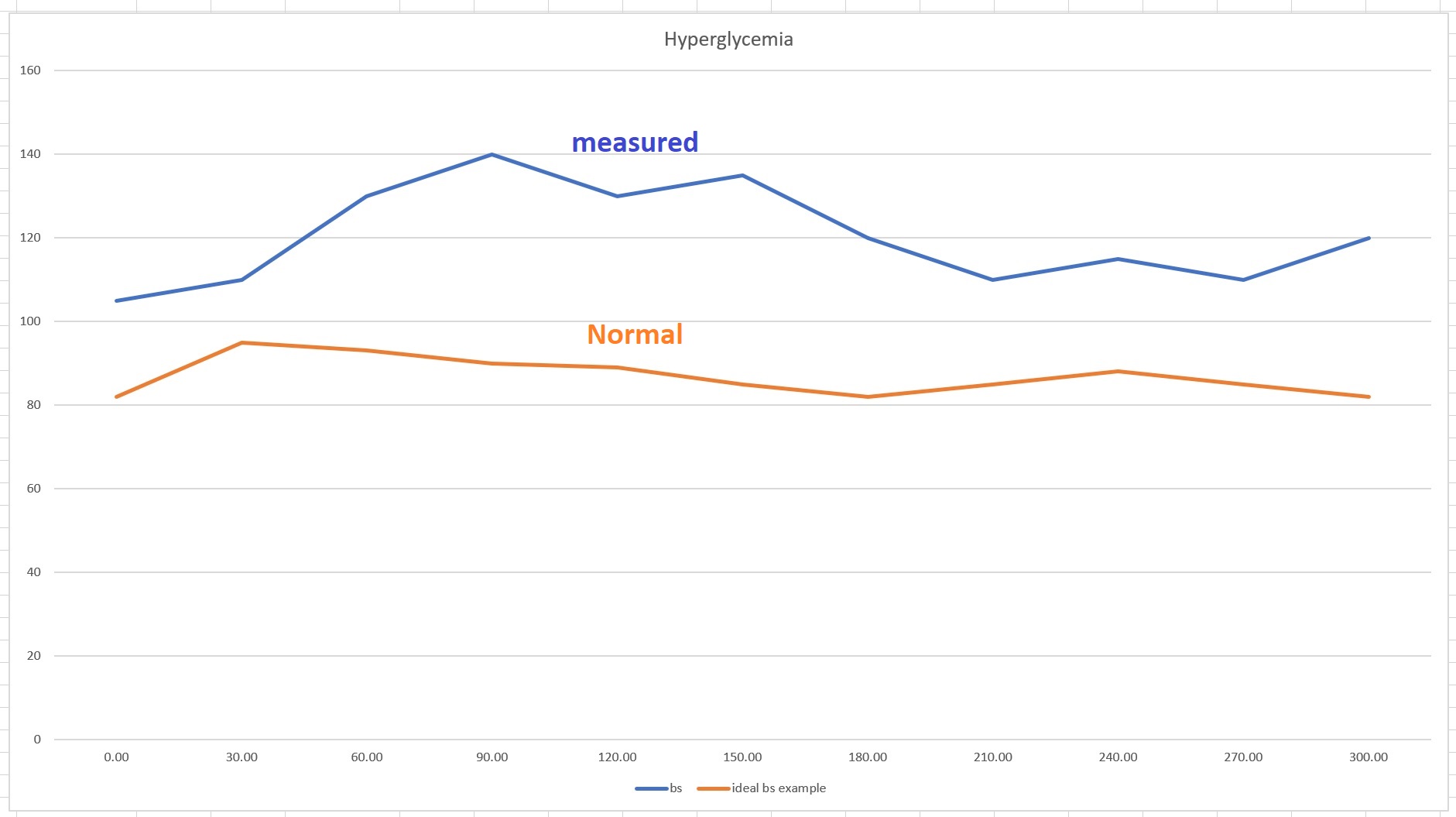

- Fasting: 105 mg/dl

- 1 hour after OGTT: 172 mg/dl

- 2 hours after OGTT: 125 mg/dl

Note that all three are unremarkable though her fasting glucose is higher than the desired <99 mg/dl (<5.5 mmol/L) but it is not flagged—the Dawn Phenomenon may increase fasting blood glucose and so slight elevations are often ignored, as they were here. Both her 1-hour and 2-hour tests show normal.

A key important point to make here is that if you live in the US or Canada, this is where your OGTT ends, you are patted on the shoulders “job well done” and sent home. This is the core of the problem. When trying to find out if someone has T2D or IR, one needs to check insulin. The glucose measure is used as a proxy but is it really a good proxy? Not at all. I explain later—let’s continue to two other measures Nicole received, none of which would have been performed in North America, but which are the most critical in understanding whether one has T2D.

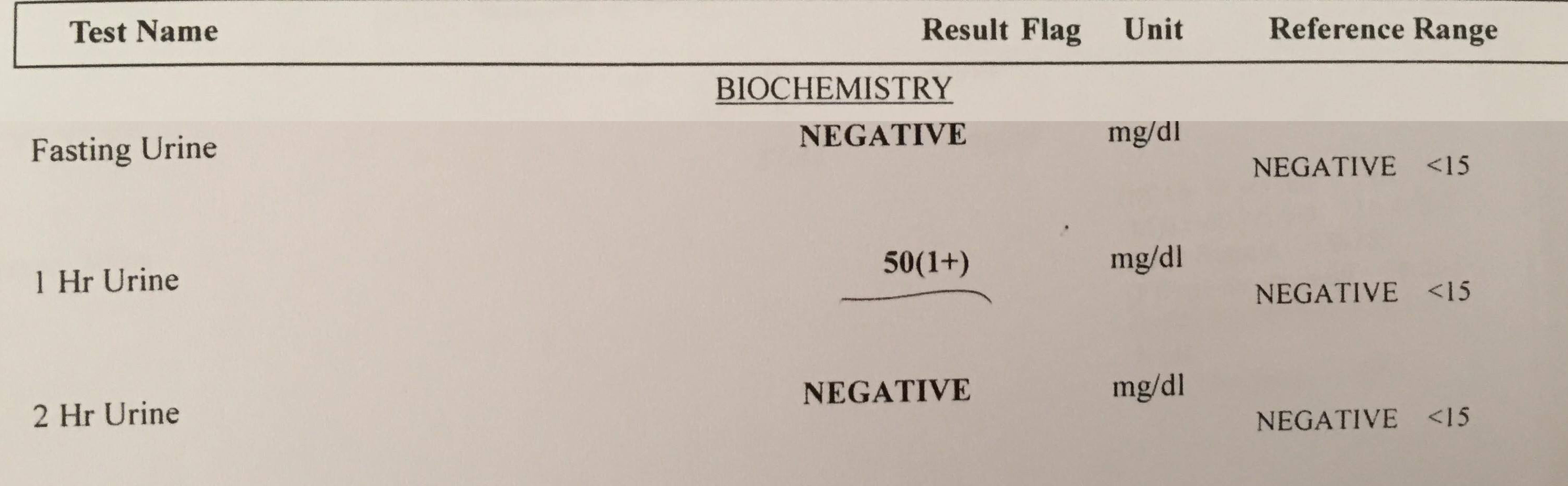

The Urine Test

For a metabolically healthy person, glucose is never found in the urine. Glucose is an important energy source for some organs (not all), and in prehistoric times glucose was not easy to come by. As a result, a healthy body converts all excess glucose (what cannot be used immediately) by the liver into glycogen or fat to be stored for the future as energy. Glucose can be found in the urine of those with a compromised metabolic system, because they have a sluggish glucose absorption as a result of IR, and they urinate out the glucose that was not possible to absorb and convert into stored energy.

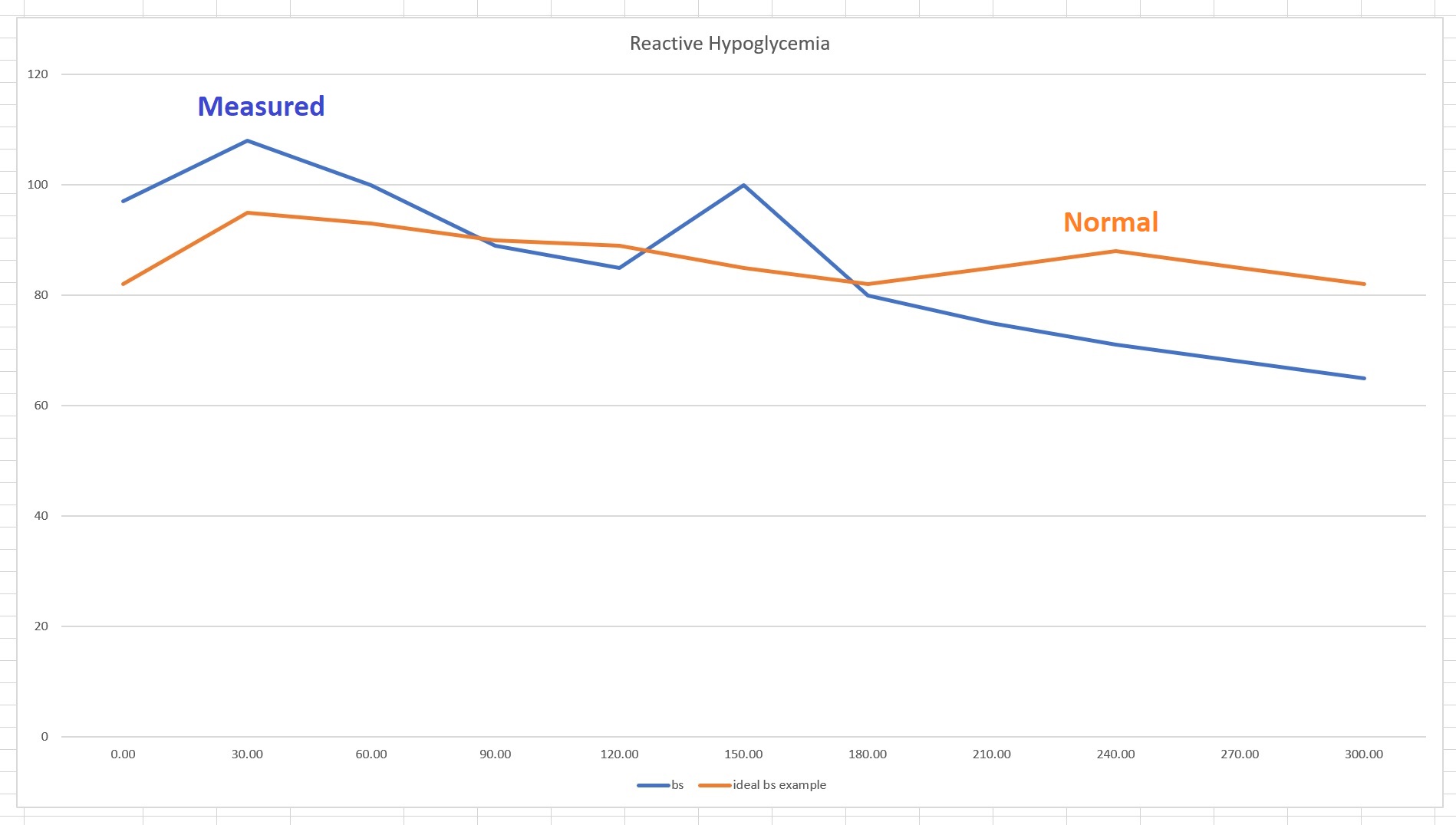

In the case of Nicole, while her blood glucose levels tested normal, the first sign of trouble shows in the 1-hour mark when there is glucose in her urine.

Note the 1-hour reading with 50 mg/dl glucose in the urine, while the accepted lab range is <15 mg/dl. Her urine contains over 3 times normal glucose amount. This is a major sign of inefficient glucose processing and of serious metabolic disease.

I need to remind the reader again: urine test is not provided with the OGTT in North America. I believe that this is a big mistake.

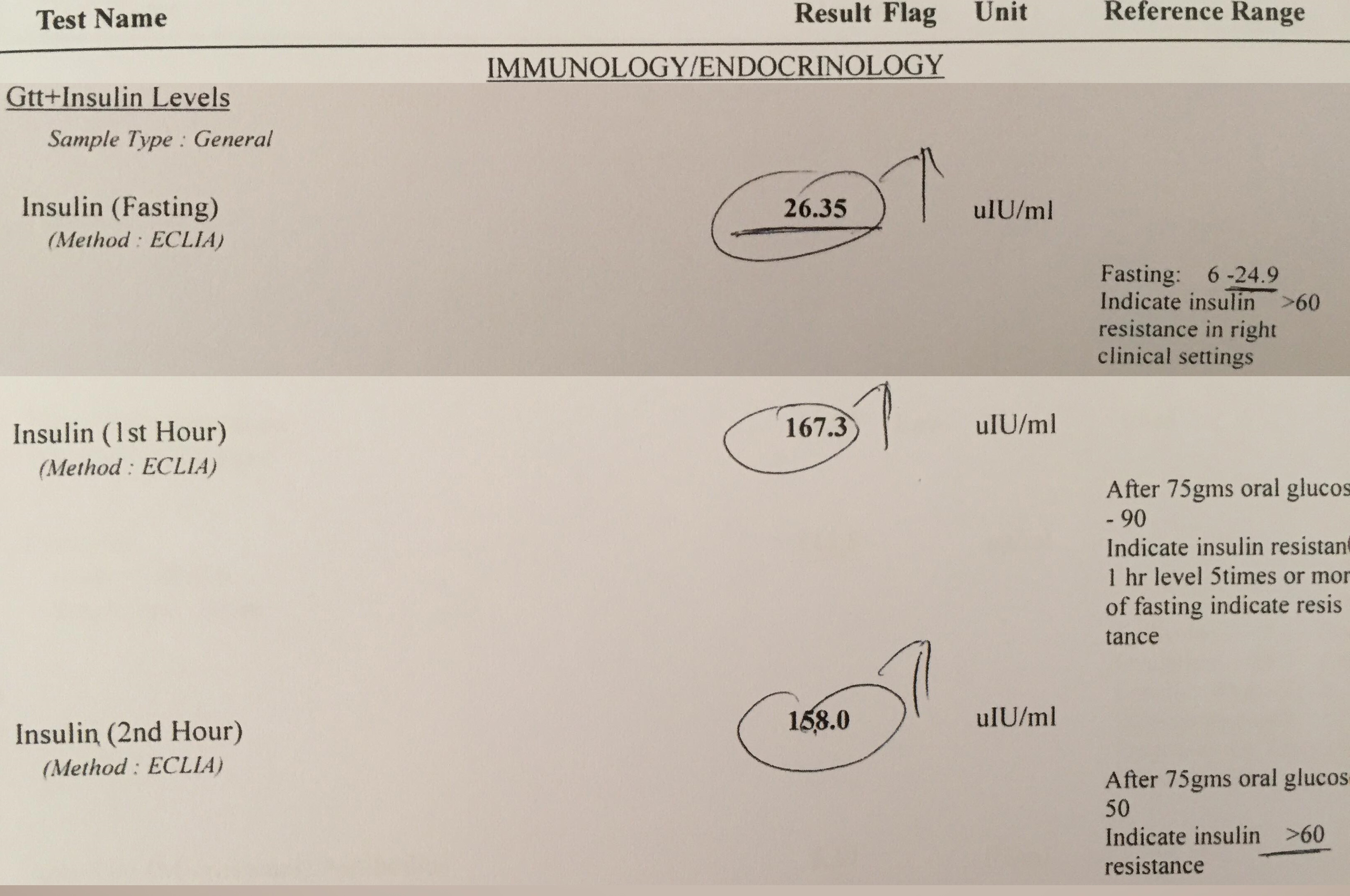

The Insulin Test

In the US, in order to get your fasting insulin test, you need to beg your doctor. Many healthcare facilities will refuse to offer it and insurance will not cover the associated costs in most places. This is the biggest mistake of them all. If we are looking for insulin resistance, why are we not checking insulin? Let’s see how Nicole did with her insulin test.

Look at how high her insulin is. While the lab range noted here is 6-24.9 ulU/ml, in reality the preferred range is 4-11, normal lab range is 2-22, where 5 uIU/ml is ideal. Her fasting insulin is over 5 times what would be considered as normal in the US and it is above normal of the acceptable by this lab as well. The one-hour postprandial (PP)—meaning after glucose solution—insulin should have been <90 uIU/ml max (hers is 165.3, which is nearly twice the maximum). The two-hour insulin PP should be <60 and Nicole’s remains high at 158, about 2.5 times the maximum (the lab range of >60 is already metabolically ill). As you see, with time passing, her insulin remains increasingly higher than normal. This is a very slow reduction. The high absolute number is not the only thing that matters. How long insulin stays high matters as well.

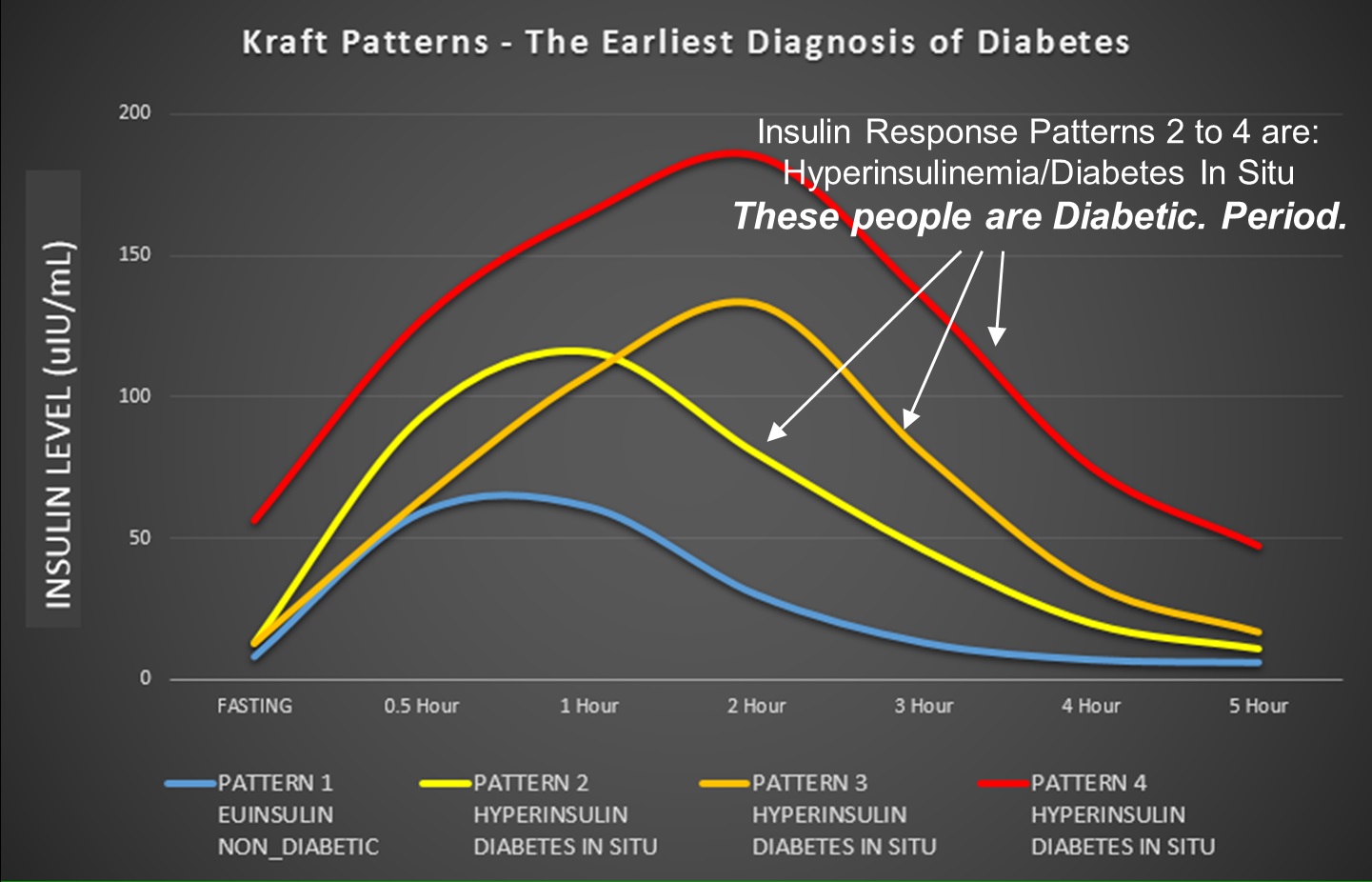

Diabetes In-Situ

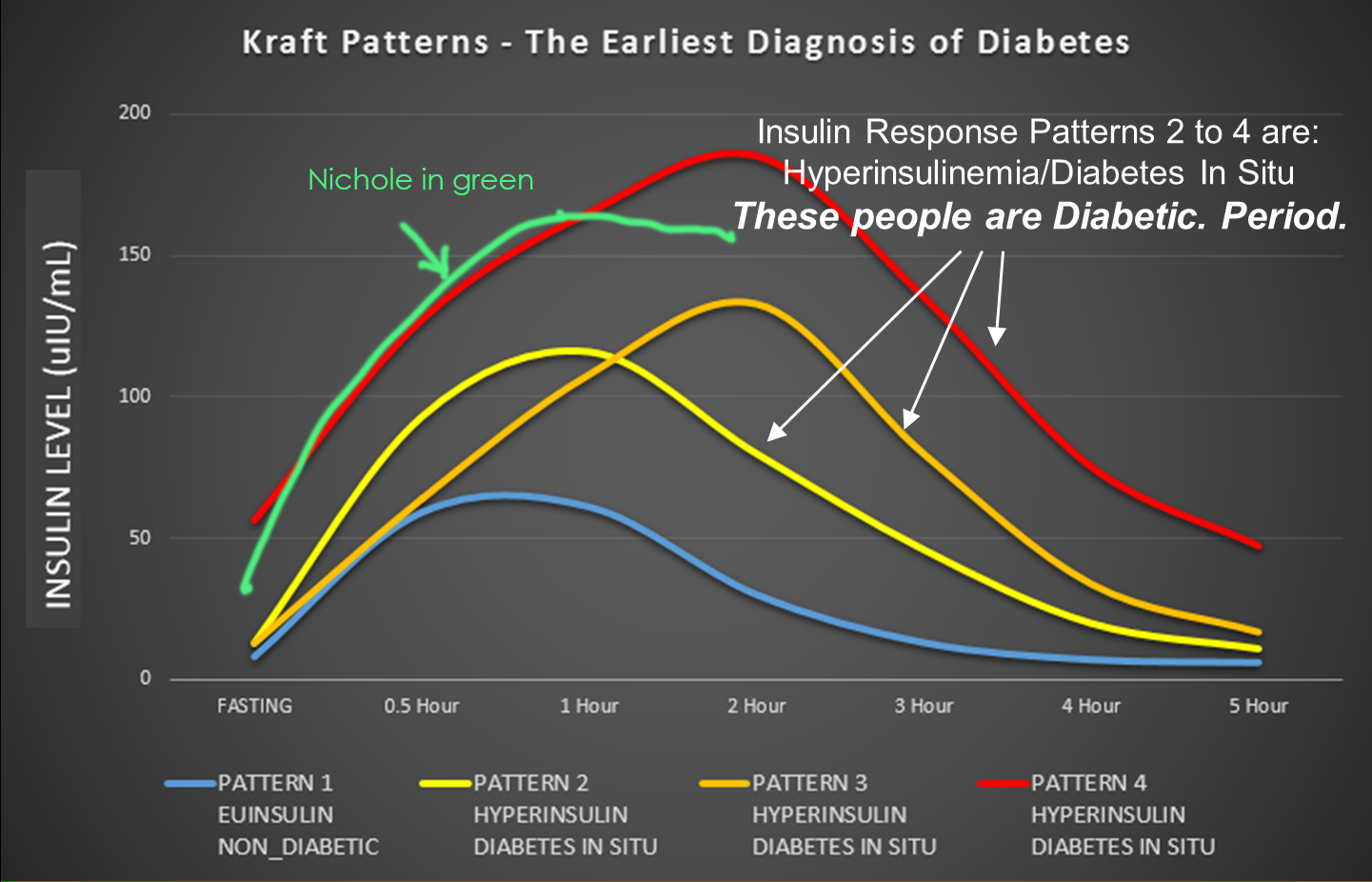

Dr. Joseph Kraft, in his book “Diabetes Epidemic & You” discusses how easily patients with T2D (he called this diabetes in situ) passed OGTT in great numbers with flying colors as if they had no metabolic health concerns at all. In his table, 40% of those with diabetes in situ had fasting blood glucose <110 mg/dl1 (page 6)–just like Nicole. A perfect diagram was designed by Ivor Cummins, which places the 4 types of insulin responses on one graph for easy viewing.

See the original of this graph here.

Looking at Nicole’s lab results and superimposing her fasting and two hours of insulin reading on this graph:

What you see is that she fits right somewhere along Pattern 4, meaning full blown type 2 diabetes. Of course, her doctor prescribed for her medication immediately, but she decided to follow the dietary approach to T2D reversal instead of the medicinal approach—more on this at the end.

Why Do We Test Blood Glucose Instead of Insulin?

Nicole’s blood glucose test shows absolutely no T2D and barely even the slightest possibility of IR with a slightly higher fasting glucose than usual. Why do we use blood glucose as a proxy for insulin? While the reasoning defies my logic, I can speculate.

- It is cheap to measure blood glucose. Blood glucose meters are sold everywhere very inexpensively so lab tests are only needed for an OGTT.

- It is easy to read what a blood glucose test shows.

- People can easily measure their blood glucose at home several times a day, before meals, after meals, etc.

- Insulin is harder to test and is more expensive.

- Many medical practitioners don’t understand insulin.

The following quote explains it all:

“Measuring insulin levels is an unnecessary health care expenditure, added Dr. Arslanian, the Richard L. Day Endowed Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh. “We’re already talking about how expensive health care costs are in the United States. Why do that when your eyes can tell you — or the body mass index can tell you. If you’re obese, the insulin level will be higher. You treat the obesity and the insulin comes down. You don’t treat the insulin.” (see here)

Chicken or the Egg?

In most medical literature, metabolic disorders, such as T2D and IR, start with obesity. However, obesity is the outcome of IR and T2D and not the cause. To understand this, doctors would have to recall something important from their rote memory from many years ago when they started med school. The role of insulin is to take excess glucose out of the blood and pile it into the liver, whose job it is to store it as fat. Glucose cannot be stored as glucose for several reasons, of which one reason is that excess glucose in the blood is toxic. Storage of glucose presents a space issue as well: a glucose molecule is C6H12O6. If you recognize the formula of water (H2O), you can see that a single glucose molecule incorporates 6 water molecules. And water is heavy. Storing glucose would mean storing a lot of water as well, unfortunately not part of the human physiology.

Insulin takes glucose to the liver, where the liver extracts the water and discards it, converts the remaining glucose-remnant into fat, and deposits all into adipocytes (fat cells). Part of the reason for excess urination by T2D patients is this constant removal of the extra water (polyuria) that is attached to glucose and excess thirst (polydipsia), because the water homeostasis is disrupted.

Thus, long before T2D shows up on any medical radar, your body is building up a hefty fat storage. Where that fat is stored, also matters and is largely genetic. Some people are genetically predisposed to have much of this fat deposited as ectopic fat (inside organs). They may look thin but their organs, such as liver (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) or pancreas are full of fat. These people are called TOFI (Thin Outside Fat Inside) and just by looking at them, there is no way to assess their metabolic status.

On the flip side, there are many people who are genetically blessed and though are obese, have no metabolic disease at all. As a result, making a metabolic disease judgement based on “looks” is deceiving. The official criteria for the chance of receiving a T2D screening test is as follows:

Criteria for Testing for Diabetes or Prediabetes in Asymptomatic Adults

- Testing should be considered in overweight or obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 or ≥23 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) adults who have one or more of the following risk factors:

- First-degree relative with diabetes

- High-risk race/ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander)

- History of CVD

- Hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg or on therapy for hypertension)

- HDL cholesterol level <35 mg/dL (0.90 mmol/L) and/or a triglyceride level >250 mg/dL (2.82 mmol/L)

- Women with polycystic ovary syndrome

- Physical inactivity

- Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance (e.g., severe obesity, acanthosis nigricans)

- Patients with prediabetes (A1C ≥5.7% [39 mmol/mol], IGT, or IFG) should be tested yearly.

Note that the list of criteria is based on the pre-qualification of a higher than accepted BMI (body mass index). As noted earlier, there are TOFI who have low BMI and have T2D and then there are the obese with large BMI who have no T2D. The criteria is biased based on “obesity causes T2D” rather than the truth, which is “T2D causes obesity”.

Migraine and T2D

I work with thousands of migraineurs and find that nearly all (at least of those who so far tested) have IR and some T2D, yet nearly all also have normal or below normal BMI, low blood pressure, normal triglycerides, great HDL cholesterol levels, may not have anyone in the family with T2D, have no CVD (coronary vascular disease), may not have polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and are physically active (many are athletes). In other words, the migraineurs I work with would not meet any of the above criteria set as the guideline by which to screen for T2D.

Migraine sufferers are not the only ones that are misdiagnosed, since nearly all young people don’t fit the model for testing criteria. However, even if testing is recommended, they only test blood glucose. So, when is T2D diagnosed? Often decades after the condition has already started. T2D often has no symptoms until it is in advanced stage. T2D is preventable and can be put to remission by eating a low carbohydrate diet. T2D is discoverable by the insulin test. If your doctor doesn’t want to prescribe a fasting insulin blood test, my recommendation is: change doctor. If all else fails, in the US you can get your insulin blood test via private services for a fee.

Case Study Conclusion

Nicole is a very lucky person that the country she lives in tested her for urine and insulin in addition to glucose. This likely saved her from years of agonizing pain, loss of vision, and loss of limbs. It saved her from a most horrific death of slowly rotting from the inside from excess glucose. She is currently on a very low carbohydrate diet (ketogenic) and recovering steadily.

Sources

- Kraft, J., R;. Diabetes Epidemic & You. revision 1 edn, (Trafford, 2011).

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.