In the last essay, we talked about viewing reality as holographic, where what we perceive exists against a backdrop and within a context. In other words, we do not perceive things as they are but only as they relate to other things (think of the shadows on the wall in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave). Here, I will explore how such a framework might influence the way we understand metabolism and pH—how the body balances its internal milieu.

Twin Variables of Life: Density and Speed

After I moved out of a moldy house in 2014, I suffered from fatigue, orthostatic intolerance, and viral re-activation. Nutritionally, it seemed everything in my body was in short supply. I needed so many minerals and so many B vitamins. The simplest act of exertion—climbing the steps to emerge from the underground subway—could literally take the life out of me.

Metabolically, I felt like a blender on full speed. The more I added “flour” (minerals), increasing my density, the more I had to add B vitamins, to increase my speed. The reverse was also true. The more I increased my B vitamins, the more density (vitamin D, calcium, iron) I seemed to need. My batter’s “consistency” was technically correct, but I was achieving it much more strenuously than a healthy person. With my blender on full speed, and my batter at maximum density, I had no energy left over after the baseline metabolic task of keeping myself alive.

Parting the Veil on pH7

My “consistency”? Yes. In the physical/holographic universe model that we explored briefly last week, the present has a proper consistency—the consistency of light. Light’s consistency, like pH7, can look like a simple number—but contain hidden information.

For example, if we think of a 75-degree room as essential to life—the way we think of ~pH7—there are different ways to achieve 75 degrees. I can turn the heat up all the way in a room that is freezing, but because the heat is on, I do not perceive the true coldness of the room. I can turn the A/C up all the way in a room that is scorching, but because the A/C is on, I do not perceive the true heat of the room. In each instance, my brain will read only the “net effect”: 75 degrees—but that single number is hiding two other numbers. Part the curtain, and it is not a “flat” 75-degree room. It is a freezing room that is heating up or a scorching room that is cooling down.

When I was very sick, it felt as if I were “freezing and scorching” at the same time. How could that be? I had drenching night sweats all night every night for two years—a half-dozen years before menopause. Upon testing, my hormone panel was normal. So what was causing the dysregulation? Like the example above, was my pH7 masking two other numbers—one that was too low, and another that was too high? I think I was pushing too much sodium into the cell during the day, then having to dump too much sodium at night.

My brain’s understanding of pH—the width of my pendulum swing, so to speak—was too wide. In this model, pH is like a pendulum that must net to an upright position of “green” (pH7). But, behind the scenes, the swing can be too narrow or too wide. pH7 is like 75 degrees. If I am too acidic (too fast) metabolically, I can keep the terrain too alkaline—like a hot room with the A/C on. If I am too alkaline (too slow) metabolically, I can keep the terrain too acidic—like a cold room with the heat on. Could we be using changes in pH to atone for changes in the metabolic rate?

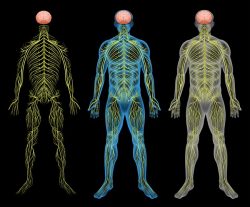

In these models, pH—the powers of hydrogen—is a stand-in for the speed of light. The core metabolic rate is a stand-in for the speed of time. The two will move in tandem. When light is too slow (too wide), time has to oscillate too quickly (ME/CFS, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?). When light is too fast (too narrow), time has to oscillate too slowly (LSD, Autism?).

If I have a recording of a sonata that is too slow, I can compensate by increasing the playback speed. Now the music sounds right to my ear—but, in fact, it is “too slow and too fast” at the same time. This is what I mean by the “hidden variables” of a holographic universe. What we hear is not necessarily song as song. We should consider the speed of the rendering. Time.

Let’s say this is a holographic universe; one where the brain renders reality based upon the twin variables of light’s density and speed. As light’s density increases (think of the mixing bowl), so does its speed. When we see light’s speed increase, we don’t realize it, but elsewhere, its density is increasing. When we see light’s density increase, we don’t realize that elsewhere, its speed is increasing. We are observing the same equation—the same “aquarium” in the words of David Bohm—from different sides.

Perception of Time Is Subjective

Are we designed to harmonize with the speed of light? Is there light at the center of every skull? I am interested in the small crystal called the pineal gland, dubbed the “seat of the soul” by René Descartes.

My pineal gland reads the speed of light in my environment, and helps me to set my metabolic rate accordingly. Here’s the problem, though: my pineal gland cannot read light’s speed objectively, because light’s speed is not objective. In these models, light’s speed and density increase in tandem.

If my pineal gland is too dense, or is calcified with minerals, it will read light’s speed as faster than it is. If my pineal gland is too diffuse—not dense enough, or under too little pressure—it will read light’s speed as slower than it is.

Then what happens?

If I read light’s speed as faster than it is, I set my core metabolic rate too high. I am technically in metabolic acidosis—generating too much acid via metabolism. To be too acidic is no small matter; pH7 is life-critical. If my metabolic rate is too fast, too acidic, I will compensate by creating alkalinity by whatever means necessary. I can pull calcium from my bones and teeth or I can manufacture ammonia, as a metabolic corrective, to maintain pH7 and keep myself alive.

I am alive, yes, but I am effectively burning and freezing at the same time.

Once this happens, it is easy to find myself metabolically trapped. I want to slow my metabolic rate, to generate less acid via metabolism, but first I need to lower my too-alkaline pH. I want to lower my alkaline pH, but first I need to slow my metabolic rate. It is as if both sides are saying: you first. It may sound like a game of chicken, but it is no game. As mentioned, pH7 is necessary for life.

Meanwhile, I am swimming in ammonia and its by-products, which are exquisitely toxic to the brain. On my organic acids test, the practitioner said my ammonia markers were the highest she had ever seen. I could feel it happening. I saw my body breaking down muscle to manufacture ammonia. I saw bags start to swell beneath my eyes. It felt as if I had synchronized with the accelerated rate of decay—the mold—in my old house. Instead of being a true pH7, I was a pH2 against a pH12 background—scorching and freezing at the same time.

Searching for a Solution

I decided to cut out all glyphosate (the pesticide known commercially as Roundup) and eat only organic food. After three weeks, I breathed a deep sigh of relief, as if every cell of my body could suddenly breathe again. All the fake iron (non-organic bread and pasta is “enriched” with non-heme iron) and ersatz manganese (glyphosate can cause toxic accumulation of manganese in the brainstem) were destroying my internal navigation system.

For a couple of years, I followed the Amy Yasko protocol for neurological inflammation, where she has been able to use (for instance) extremely small doses of B12 to solve the “you first” problem of metabolic gridlock. I also had some success with the “pyroluria” protocol (high doses of zinc and B6) for a while. In the process, I started to look at links between human health and physics, and began to see disease as fundamentally metabolic.

Mold: Matter Decaying Backward

Perhaps being in the presence of mold (matter decaying backward) shifted my brain’s understanding of time. In these models, time exists in a context, against a backdrop. When time is too fast, light spins backward. Light cannot eclipse the speed of light.

My Krebs cycle does not simply run in forward, to make energy. It can also run backward, to make matter. When my Krebs cycle spins in reverse, I endogenously (internally) manufacture oxalate, a crystal found in plants capable of photosynthesis. Could light “spinning in reverse” be involved in oncogenesis—when cells become cancerous? Oxalate is known to induce breast cancer.

The following is from Nick Lane in Quanta: “A Biochemist’s View of Life’s Origin Reframes Cancer and Aging.”

About 10 years ago, the cancer community was amazed by the discovery that in some cancers, mutations can lead to parts of the Krebs cycle running backward. It came as quite a shock because the Krebs cycle is usually taught as only spinning forward to generate energy. But it turns out that while a cancer cell does need energy, what it really needs even more is carbon-based building blocks for growth. So the whole field of oncology began to see this reversal of the Krebs cycle as a kind of metabolic rewiring that helps cancer cells grow.

Conceivably, what we consider the linear and forward march of time is nothing more than an illusion. Time “moves forward” only to the degree that it has first “moved backward”—like a rock drawn back in a sling. When the trajectory of the rock reaches the midpoint—the “zero-point” of the starting position—its movement continues, but the character of the movement flips. It is no longer accelerating in the context of deceleration (heating up in a cold room). Now it is decelerating in the context of acceleration (cooling down in a hot room). Who or what decides where the “zero-point” is? That is the million-dollar question. In physics, everything boils down to one all-important thing: the observer. We need to consider the observer when we practice medicine.

Every cell is observing itself. I can be a “flat” pH7, but I can also draw back from the boundary, like a rock in a sling. When I draw back, I acquire dark energy. Acidity. Sodium. Now, my pH7 has another layer to it: I am sodium inside potassium. Like an ice skater pulling in for a twirl, it is as if I have become smaller, denser, and colder—while increasing my speed. On the surface, I still look like “water,” like pH7, like light, but I am matter inside energy. Then, from my new position, I can draw back again. And again. In a sense, each time I draw back, I am imploding.

Individual Clocks

This model is arguing that a proper understanding of the relative speeds of light and time is critical to good health and to the efficient functioning of metabolism. The body monitors these variables and makes adjustments accordingly, but this is not done centrally, by one controller. Rather, each cell sets its own ‘clock’. Why not have each human body read time’s speed centrally, and move forward in unison? I don’t know, but perhaps this: although it leaves us vulnerable to oncogenesis and pathogenesis, the ability to cycle time at different speeds within a single organism is what allows for cell cleavage and blastulation—embryogenesis, the ability to procreate, which is arguably our greatest gift.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, and like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Feature image by Fahrul Razi on Unsplash.

I have experienced the metabolism going backwards, what could be the reason?

This series is SO thought-provoking and should be considered by more scientists. Thank you!