Postpartum depression may occur in up to 1 of every 8 pregnant women. Here, we produce a fictional representation of how it may present to you in real life, whether you are a family member, friend, or spouse. It is important to note that postpartum depression can also occur during pregnancy, and can occur as a seemingly ‘normal’ event of childbirth depression, yet postpartum depression carries more burdens and feelings of being totally overwhelmed, less in control of one’s life, anger, and rage. Gradiations of postpartum depression thus can be so subtle that you think nothing of it, yet with extreme postpartum depression, the mother is encompassed by hallucinations or voices incessantly talking to her, instructing her to harm herself and/or her child. The number one cause of death in new mothers is suicide, with thoughts of suicide and self-inflicted harm as very serious problems (Moses-Koldo, 2009; Lindahl, 2005)

Recognizing Postpartum Depression: A Case Scenario

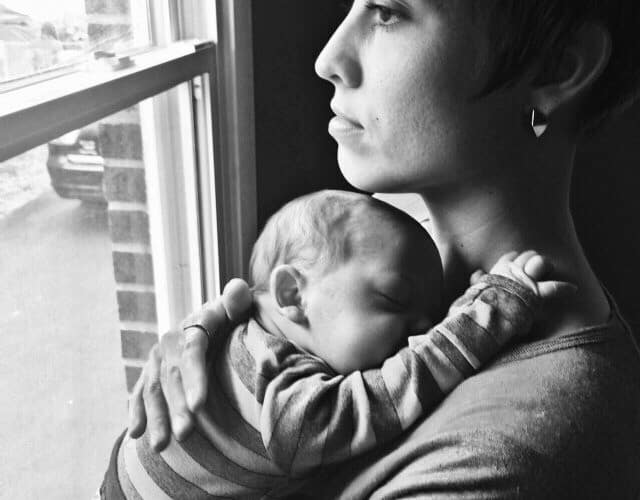

Her name was Anna, little Anna. She soundly slept in the car all the way home, as if she was going to be a “good baby.” Her little hands scrunched up into balls every so often, and although she slept, her eyes moved just so, proving that she was in rapid eye movement sleep.

In the front seat, the mother with the straggly hair, Josephina, put on the smiling face of a clown. None of the doctors had noticed a thing that was wrong with her, even though she did complain to one good-looking young doctor in training. All he did was scoff at her. He made her feel ashamed and silly. But inwardly, she was petrified, just petrified, of being left alone with this little being that depended on her for everything. Her thoughts of throwing the baby off the ledge and jumping in after her, like diving into a pool, continued to grow in their intensity, frequency, and enormity. Josephine was scared to turn the lock and enter back into her apartment that represented loneliness, so she let her friend Marissa do it. Marissa stayed long enough to lay the baby in a clothes drawer on the floor, surrounded by blankets so soft that they still smelled like fabric softener.

As Josephine said her goodbyes and closed the front door with barely a squeak, she silently turned her back onto the white painted door. Slowly, ever so slowly, she slid down the door crying silent yet violent tears, body heaving, until at last she was sitting on the floor. All the thoughts continued to pound in her head: “Throw the baby out the balcony! Jump in and just dive in after her!” Her unkempt hands held her head, fighting the increasing enormity of the battle. “Do it!” “Do it!” Josephine grasped aloud at these intrusive thoughts that didn’t belong in her brain. She knew they didn’t belong there, and she felt cursed upon realizing what an ungrateful new mother she must be. Maybe she didn’t deserve to have this little Anna at all. Laden with guilt, she rocked herself on the floor and thankfully, the baby slept through it all.

She thought, as she wiped her tears for the millionth time, “Do all mothers feel this way? Do they all go through this? Aren’t I supposed to be happy?” Of course she was tired. No, she was exhausted. Of course she had continuing insomnia and her mood swings were unpredictable and covered the expanse of linear possibilities: one minute laughing and the next minute, crying. She looked at her hands and they were trembling as another layer of guilt fell over her like a black sheet at Halloween, showing only her eyes. She ran to the bathroom and threw up for the third day in a row. The thoughts turned into guilt and shame, chastising her very soul. She should be happy, but she wasn’t. She should be having happy thoughts, but she wasn’t. Another black sheet of guilt and remorse fell upon her, and her shoulders drooped with the heavy weight that she bore. She wanted to scream! She wanted to run! And yes! She wanted to jump over that balcony!

The exhaustion, insomnia, and the overwhelming state of mind were perfectly normal for any new or seasoned mother, indeed. Each pregnancy was different, but all pregnancies carry with them the dawning of another layer of new responsibilities, the screaming of a helpless being, the bursting of the mother’s eardrums, a hundredfold changes in circulating hormones, and concurrent inflammatory reactions that all but wreak havoc on a woman’s body. If she also suffers from poor nutritional status, this further compounds the biochemical reactions in her body, adding another twist of lime. When the baby cries, the breasts drip milk; it’s just automatic. Her body is a robotic machine, connected inexplicably to her baby, just as if the umbilical cord had never been cut. Mother and child are still tied together. Like a parasite of alien proportions, the baby sucks at her breasts and also sucks at her life.

Transition to Motherhood: When Postpartum Depression Rears its Ugly Head

For most women, this depression hits its worst on the day of the “Third Day” blues. Then it seemingly disappears just as quickly as it came. The blues gently fade away with day number four; they can last a week or two. Mom is smiling and laughing again. She has no thought of harm to herself or her baby.

Risk factors and symptoms for postpartum depression are broad and ill-defined. Some research focuses on the sadness, the lack of energy and the depression, while other research suggests postpartum depression is not really a depression in the classic sense, but an anxious feeling of unease, marked by increased intrusive thoughts, like those Josephina experienced. In truth, how and when women present with postpartum depression is highly variable. The symptoms can begin in pregnancy, 3-6 weeks after childbirth, or really anytime. For more information about pregnancy and postpartum psychiatric distress, the following articles may be helpful: Framing the Pregnancy Postpartum Hormone Mood Debate, Beyond Depression: Understanding Perinatal Mental Health, Maternal Psychiatric Disturbances and Hormones, What Causes Postpartum Depression? You might also consider reading the personal stories listed on our blog about postpartum depression. If someone you know is suffering from postpartum depression after childbirth and you reach out, you may save a life.

Reaching Out to a Postpartum Woman

So you are the one that had met Josephina in the market before she had her baby, and you exchanged phone numbers with her. You are new in town, live comfortably with your husband and two toddlers, and are looking for a friend. You want another baby, but your husband does not. You decide to call Josephina to see how she is doing.

“Hi Josephina. This is Elena. Remember we met in the grocery store? My kids and I were wondering if we can stop by and visit. We have a gift for you and the baby. Call us back when you can, ok?” You leave a message on her cell phone, as Josephina did not pick up. She was too busy staring at the floor, feeling too sad and guilty to move.

You call her again the next day, after Josephina had awakened in a sweaty bed, had only two hours of sleep, and felt like a walking zombie. This time, Josephina picked up the phone and said you could come visit.

You and your children arrived to her apartment door knowing that it was the right one; you could hear the screaming baby all the way down the hallway. You, being so perceptive, also noted that you could not hear any words of consolation, no kisses, no whispers or singing of lullabies. Josephina answered the door, walking away without saying hello. She mumbled something about going to get the baby, and came back from the bedroom with little Anna. You let your children play with the baby laying in her portable car seat, while you pulled Josephina aside.

“What’s wrong, honey? You don’t look so good to me.” Clearly, Josephina was sorely depressed and had not yet bonded with her baby. She was thin as a rail, malnourished, unkempt to the extreme, and you sought immediate help for a diagnosis of Postpartum Depression. You told Josephina to go take a nice bath or shower, put on some clean clothes, and by the time she was finished, you would have a few phone numbers for her to call, a few resources for her to use so that she could get help and not be all alone with this beautiful baby girl.

Josephina stood still. She was catatonic. Immobilized. So you turned on the shower, took away the razor blades on the tub, and got her undressed. You went back and forth, checking on the baby, looking for baby formula, and watching Josephina shower. “Put the shampoo on first, Josephina.” You got internet access on your iPhone and did a search for Postpartum Depression. Finding a page full of resources, you checked on the baby and the children, then on Josephina again, saying, “Okay, Josephina, time to do shampoo number two!”

And you started making phone calls. You learned that Postpartum Depression is the #1 complication of childbirth. 1 in 8 women suffer from Postpartum Depression (that we know of), many going undiagnosed.

Approaches to Postpartum Depression

Treating postpartum depression presents unique challenges and concerns compared to treating depression or other mental health issues in non-pregnant women. In addition to the concerns about breastfeeding, new moms are sleep-deprived, sometimes feel isolated, have just undergone enormous hormonal changes and are often nutritionally deficient. Tackling these issues may require multiple treatment modalities. Here is an overview of the standard approaches to postpartum depression treatment.

- Counseling/Psychosocial Assessment and Support. This first-line road to better mental health helps with talking about your thoughts, coping mechanisms, and problem-solving; removal of solitude can make a huge difference. In addition to individual therapy, a number of postpartum and parenting support groups exist in every community, and many referral systems are in place through helpline resources, such as Resources International “Get Help” http://www.postpartum.net/Get-Help.aspx .

- Anti-depressants, anxiolytics and/or other medications. A common method to treat postpartum depression, but it is not without controversy and risk. If you are breastfeeding, be sure and talk to your doctor about which drug(s) to go on. Medications may pass from the mother through breast milk to the baby. It is crucial to note that with adolescents and young adults and postpartum women some antidepressants may lead to “…increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior…” exacerbating the situation. (NIH; Package Insert). You may want to seek at least two opinions before starting antidepressant therapy.

- Hormone therapy. Still an area of controversy, some clinicians advocate attenuating the decrease in postpartum estradiol with transdermal estradiol (Moses-Kolo, 2009). The thinking is that if this hormone declines more gradually over time, the symptoms of postpartum depression may lessen or diminish completely. The research is mixed. Other research suggests declines in progesterone are linked to symptoms and thus, treating with progesterone may alleviate the symptoms. (It should be noted, however, that synthetic progesterone as is found in birth control pills, exacerbates postpartum depressive symptoms and should be avoided.) And yet, other research suggests that it is not the decline in estrogens or progesterone that spur postpartum symptoms, but rather abnormal fluxes in androgen hormones. It should be noted that undiagnosed thyroid conditions are common in women, especially during pregnancy and following childbirth, and so, thyroid disease might also be responsible for the onset of symptoms. With postpartum psychiatric issues, thyroid disease should always be tested for and treated if found, ideally prior to beginning other therapeutic interventions.

- Ongoing NIH Clinical Trial: If you are interested in participating in a clinical study on mood changes after childbirth whether or not you have had postpartum depression before, you can visit the NIH website here. This Screening Program to Evaluate Women with Postpartum-related Mood and Behavioral Disorders (Study 03-M-0138) is currently recruiting volunteers. Selected patients may be asked to participate in a follow-up study using estradiol for postpartum depression.

- Nutritional therapy. Emerging evidence connects nutritional deficits to postpartum psychiatric symptoms. With the added physical burden of pregnancy and childbirth, previously hidden nutritional deficits become unmasked and can initiate a cascade of psychiatric and inflammatory reactions.

From Postpartum Depression to Psychosis

“Put on your conditioner now, Josephina,” you instruct, as you sit and make some phone calls. Even your own hands are shaking now, because you don’t want her to lose her baby to the State, but you also don’t want her to take her baby and jump off the balcony. By this time, she has told you everything. It is almost too much. You are overwhelmed and you know that she needs professional help. You know that the next 15 minutes will be crucial, even staggering, in how you approach her illness. Your concern for how this will impact the rest of her life almost leaves you frozen, but you know that you know that you know that two lives hinge on your decisions. And to further confound matters, you know that none of your options will be optimal. No matter which path you choose, you could be perceived as ‘the bad guy’. The diagnosis may be made, but the treatment options are limited and wrought with controversy. There is no easy answer. Every choice comes with a consequence and you can only do your best.

Frightened at the unknown future results of your own actions, you begin to doubt yourself as pessimistic thoughts cry out: “What if I make the wrong decision?” You oscillate between worries, “If I do nothing and she hurts herself, it would be my fault.” On the other hand, “But if I call 911 and they take the baby from her, I would have to live knowing that I did that to her and the baby.” Back and forth you go. The reasonable, pragmatic side of you knows for a fact that Josephina can not take care of herself and can not be left alone with her baby. For one moment, the squeals of the baby break through the coo’s of your own children’s laughter, almost as a reminder, say yes! It is a reminder of how things are ‘supposed’ to be. Again, you internalize this conclusion, knowing that you need help yourself. You cannot bear this burden alone. You have no experience with this, you dread making a life-long or fatal mistake. You are smothered into a corner to do something NOW!

So you decide to call for help.

When Postpartum Depression Becomes an Emergency: Finding Help

Debating psychotic disorders and parenting, and the relevance of a mother’s children for general adult psychiatric services was, in 2000, Louise Howard’s project as a Research Fellow. She stated that women with psychiatric issues who become pregnant should be specifically identified for further study, assessment, and improved outcomes, considering their children. The impact of the parent’s illness on the children, as well as a need for supportive services, needed further study.

In 2000 in the UK, a woman could voluntarily admit herself to a the first psychiatric unit, the first women-only residential mental health crisis unit in Drayton Park, North London, where children could be admitted with their mothers (Killaspy, 2000). Residential alternatives to inpatient ward care in England have since been shown to provide more patient autonomy, greater satisfaction, less coercion, more ‘voice’, less aggression, and less anger (Osborn, 2010). Since the 1980’s, these residential units have been rampant throughout the Australia, UK, Europe, and New Zealand.

In the USA, there are many ‘postpartum depression treatment centers’ that can serve as the initial call for help, and provide care in the outpatient clinic setting. This resource seems most appropriate for women with depression who are not hysterical, hallucinating, are overcome by intrusive thoughts, or are having visions or hearing voices. For a government department (i.e., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, or SAMHSA) that is continually updated and offers local, mental health referrals, use telephone 1-800-662-4357, 1-800-662-HELP, and/or website www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov .

During the week of August 11, 2011, the U.S.’s first treatment center based on the Drayton Park, London model of inpatient mother:child care opened. This was first inpatient facility for severe postpartum depression for both mothers and babies. It is still located at the University of North Carolina’s Chapel Hill hospital’s psychiatric ward. Brown’s University has a Postpartum Day Hospital opened for mothers and their baby’s weekdays from 9 am to 5 pm (Stampler, 2011).

A bipolar woman who gets pregnant has an increased chance of having postpartum depression leading to postpartum psychosis (Marks, 1992), but she may not seek care for her needs, for fear that her baby will be taken away from her (Howard 2000). When things have escalated to the point of Mom wanting to harm herself or the baby because of voices in her teeth telling her to do so, psychosis may exist and this demands immediate emergency care. Society still places a stigma on mental illness and it is unfortunate that an involuntary admission to a psychiatric unit is usually accompanied with separation from the child(ren).

In the United States, the most common route is for the woman to be rather forcefully taken by the police to determine her fate in jail or a psychiatric ward. Nonetheless, you must call 911 for any immediate danger to self or baby. When you do, a number of things may happen depending upon the state that you reside in.

As a useful tool to help you assess whether or not you have severe postpartum depression, Harvard Medial School’s “Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale” is an online test you can take in 5 minutes.

From Bad to Worse: When Postpartum Depression Risks Harming the Mom and Baby

Poor Josephina cannot dress herself. So you help, frequently checking on the baby and your own children who are happily playing in the living room. You ask Josephina several questions, “Do you have anyone to help you with the baby? Any relatives here?” Josephina just nods her head, “No.” As you continue to help her get dressed, you ask her if she’s taking any medications. “No.” You ask her if she is still having these thoughts of jumping off the balcony and she slowly nods her head, “Yes” as her eyes widen and her eyes turn maliciously toward yours. “Get her away from me. Take her now. Please take her now and take care of her. I can’t take care of her. I beg you to please take her.”

You are in shock as you make her write it down on a piece of paper, dated and signed with her signature. You only left her for 15 seconds to check on the children, but already she had bolted with the car seat and the baby, and was trying to unlock the sliding glass door. You turn to Jimmy, the older boy and look him in the eyes. “Call 911 now.” He’s not sure why, but he can tell Mommy is in no mood for questions. As he picks up the phone, Josephina and Elena fight at the sliding glass door lock, each trying their own destination: Josephina to open it, and Elena to close it. The baby is suspended in mid-air and Elena says, “Put the baby down! Put the baby down now!” Josephina looks like a maniac now, bloodying up her fingernails on the door latch in a desperate attempt to jump off the balcony. They both hear, “Um. I’m not sure, but my Mom and a lady are fighting over a baby at the balcony.”

The little child of Elena, Cristal, starts crying. Mommy said, “Go and lock yourselves in the bathroom. Here, take the baby with you.” And in one final attempt and with all her bloody might, Elena kicked Josephina enough to sidetrack her for a microsecond. Elena forced the baby car seat out of Josephina’s grasp, and ran with all three children to the bathroom. As she turned the corner, she could see that Josephina was staring at her bloody fingernails, then looked up at her, then began to dart for the bathroom door. Elena got all the children in, and told Jimmy to lock the door. Now, the children were safe.

This 1 in 10,000 chance of a psychotic depression has turned into a police matter now, and Elena poses. She is ready to fight for all the babies. But she speaks in a calm tone, reminds Josephina of the calm shower, and gets her to sit down. Shortly thereafter, the police are at the door and they take Josephina away to book her for Child Endangerment and Danger to Self.

It’s not Josephina’s fault that her psychosis led her to this. If one person had listened to her earlier, she would have received help earlier, and this never would have happened. If she had known, she could have voluntarily turned herself in to a postpartum treatment center. If she had known, she could have taken the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale test on her own, to self-diagnose and self-realize the extent of her own depression. If only…

But there is no pity for her, no blaming the biochemical changes in her brain, much like that described in people with a brain tumor who do aggressive things without realizing it. She is ostracized as a criminal instead of as a psychiatric patient, and is sentenced to 15 years in a Woman’s Prison. Being as there are no relatives that come forward, Elena gains first temporary and then permanent Custody of little Anna, then moves away to another city. Not something she had planned at that first chance meeting in the store.

If Josephina gets a proper diagnosis, showing that she was bipolar before the pregnancy, and receives proper treatment, her chances of recovery are 100%. But there’s a catch. She may never be able to go off her medications.

To learn more about resources for postpartum depression: Resources for Postpartum Depression.

About the Author: Dr. Margaret Aranda is a USC medical school graduate, as well as an anesthesiology resident and critical care Fellow graduate of Stanford. After a tragic car accident in 2006, she unfolded her passion of writing to advance the cause of health and wellness for girls and women. You can read more of her work on her personal blog, Dr. Margaret Aranda, her Pinterest page, a page on Postpartum Depression, her author’s page at Tate Publishing or follow Dr. Aranda on twitter @DrM_ArandaMD.

References

- Howard, L. Psychotic disorders and parenting – the relevance of parents’ children for general adult psychiatric services. Psych Bull 2000; 24:324-326. http://pb.rcpsych.org/content/24/9/324.full (Accessed June 26, 2014).

- Killaspy, H., et al. Drayton Park, an alternative to hospital admission for women in acute mental crisis. Psychiatric Bulletin, 24, 101- 104. Abstract/FREE Full Text

- Lindahl, V., et al. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005 Jun;8(2):77-87. Epub 2005 May 11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15883651 (Accessed June 26, 2014).

- Marks, M.N., et. al. Contribution of psychological and social factors to psychotic and non-psychotic relapse after childbirth in women with previous histories of affective disorder. J Affect Disord, 1992: 29, 253-264.

- Moses-Kolo, E.L., et.al. Transdermal estradiol for postpartum depression: A promising treatment option. Clin Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2009; 52(3): 516-529. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2782667/ (Accesed June 26, 2014).

- NIH. Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses. Depression. FDA Warning on Antidepressants. 2011. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/index.shtml. (Accessed June 26, 2014).

- Osborn, P.J., et. al. Residential alternatives to acute in-patient care in England: satisfaction, ward atmosphere, and service user experiences. Br J Psych 2010: 197:x41-s45. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/197/Supplement_53/s41.full (Accessed June 26, 2014).

- Package Insert. Fluoxetine hydrochloride. 1987. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/018936s091lbl.pdf (Accessed June 26, 2014).

- Stampler, S. First U.S. Inpatient Clinic for Moms with PostPartum Depression Opens. Huffington Post: Parents. Oct 19, 2011. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/19/americas-first-inpatient-postpartum-depression-unit_n_931179.html (Accessed June 27, 2014).

- Treatment Centers. Study examines postpartum depression. Psychiatry/Mental Health. May 24, 2010. http://www.treatmentcenters.net/psychiatry-mental-health/study-examines-postpartum-depression/ (Accessed June 27, 2014).