In my first article on oxalate for Hormones Matter, the focus was on what oxalate is and how it could be impacting you, especially with a large increase in intake. In this article, I would like to discuss a condition called secondary hyperoxaluria, where oxalate bioaccumulates relative to diet. Diet is an important contributor to hyperoxaluria; one that is often missed in the medical literature. Keep in mind that oxalates are common plant toxins that can be found in virtually all plant foods. Many of the foods considered the healthiest, including spinach, Swiss chard, almonds and other nuts, beets, gluten free grains, turmeric and many spices, can be significant sources of oxalate in the diet. The challenge is that oxalate foods may be robbing you of minerals, creating pain and inflammation, and potentially affecting a host of systems in the body.

As I discussed in the previous post, oxalate can be a poison in sufficient dose, and oxalate poisonings are one of the most frequently reported poisonings by plants. For those of us who are pet owners, if you’ve had to run your cat to the vet when they chewed on a philodendron or a dieffenbachia, you’ve already run into the problem with acute oxalate poisoning. Both these plants have extremely high oxalate in the leaves, and pet owners are often warned.

But what if acute exposure is only the tip of the iceberg with oxalate? What if long term, non-lethal and even fairly “average” dietary exposure could be creating health problems? Research and clinical experience confirms that oxalate bioaccumulation may underlie many common and often chronic health conditions including: arthritis, certain cancers, asthma and allergies, COPD, thyroid issues and other ailments. Unfortunately, this type of oxalate problem is rarely recognized. Instead, physicians tend to focus solely on what is called primary hyperoxaluria, ignoring the larger problem of oxalate bioaccumulation and what is called secondary hyperoxaluria.

The Problem With Bioaccumulation

This is where we need to consider what might be happening slowly and subtly due to bioaccumulation. This aspect of the oxalate issue is not well researched outside of the area of primary hyperoxaluria Type 1. We know about oxalate collecting in the body for those with the genetic hyperoxaluria illnesses; we ignore the possibility completely for those who do not have this kind of diagnosis.

When we discuss primary hyperoxaluria, we are dealing with a very unique situation: the body is actually making its own oxalate via the liver. Those who have this condition are usually discovered when they are quite young, as they are already quite ill at this time. The only real solution that medicine can offer is transplantation. This can include just the liver, just the kidneys, or may include both liver and kidneys (if the kidneys have already been irreparably damaged).

When individuals are dealing with primary hyperoxaluria, it is understood that kidney stones are not the only accumulation of oxalate in the body, but that the damage can be much more widespread. Genetic hyperoxaluria can include deposition of oxalate almost anywhere, with the bones and blood vessels particularly highlighted in some sources.

For example, in a case of kidney transplantation, a 38 year old male had a kidney biopsy post transplant, and “diffuse oxalate crystal was detected in allograft kidney biopsy, whereas in the 0-hour biopsy there were no oxalate crystals.” Researchers were watching for oxalate to begin to accumulate in the new kidneys, which had no oxalate accumulation previously. This case demonstrated how varied the location of oxalate may be in the body, with oxalate being found in both eyes of the same patient. While the focus of the case study was on the benefits of transplantation and what happened with the transplanted organs, clearly the challenge is also, “Where is the oxalate going in the body if it’s not being excreted fast enough?”

In another case, transplantation of kidneys alone to help manage primary hyperoxaluria resulted in the reversal of pancytopenia. Pancytopenia is a relatively rare condition where there is bone marrow infiltration of oxalate crystals. This particular case points to how important it is to get oxalate out; with kidneys that were functioning properly, this patient was able to excrete more oxalate, and this alone allowed reversal of the bone defects.

We do have a name for oxalate accumulation systemically in the body: oxalosis. This condition can be absolutely devastating with bones, arteries, eyes, heart, nerves and other systems all being affected.

Is this actually happening at lower concentrations of oxalate in the body? Even without an oxalate-related diagnosis, there is indication that oxalate can be building up in body tissues. One good example is a study that looked at thyroid glands post-mortem, and noted that there was a direct correlation between the age of the individual and the amount of oxalate in the thyroid! Another piece of research from 1993 indicated that oxalate concentrations of the thyroid samples were dependent on age and gender. In both studies, these were “normal” human thyroids, rather than thyroid glands that had been specifically harvested for examination due to disease.

So clearly – the case for bioaccumulation can be made. While we don’t know which tissues might be more likely to accumulate oxalate, we certainly know it can happen. Given that, then what? I would argue that we are then going to have to look for the source of that oxalate. When there is no genetic hyperoxaluria, the metabolism may not be the sole culprit. That leaves dietary oxalate consumption.

The Dilemma of Secondary Hyperoxaluria

This is where a discussion regarding secondary hyperoxaluria comes in. Secondary hyperoxaluria develops with increased ingestion of high oxalate foods, high availability of oxalate precursors or gut dysbiosis. It is typically further broken down into three broad categories:

- Enteric hyperoxaluria is a condition that results from over absorption of oxalate from the diet. That could be related to gut impairment of some kind, including GI disorders such as Crohn’s, surgical interventions such as bariatric surgery, or chronic pancreatic or biliary tract disease, which also includes cystic fibrosis. (Note that the connection with cystic fibrosis is related to the SLC26A6 transporter. We’ll talk about this more later.)

- Idiopathic hyperoxaluria is a condition where the oxalate in the diet is so high that oxalate is being stored. There can also be increased endogenous production of oxalate coming from the metabolism.

- Provoked hyperoxaluria can be the result of excessive vitamin C intake, acute oxalate or ethylene glycol poisoning, pyridoxine deficiency, possible aspergillus infection and other more rare causes.

I’d argue that the most likely of these for the vast majority of people will be idiopathic hyperoxaluria, which is caused by diet. Our diets have been trending towards higher oxalate intake for the better part of 50 years. During that same time, we have seen an increase in kidney stones, which is a diagnosis closely linked to oxalate.

Note that many of us are now excreting much higher amounts of oxalate in our urine than ever before. This matters, as we diagnose hyperoxaluria by the amount of oxalate in the urine. As recently as 2019, published guidelines defined urinary oxalate excretion of 40 mg or less total per 24 hours as potential hyperoxaluria. However, new test ranges indicate oxalate excretion per 24 hours as high as 100 mg (or more) are now considered “normal”. Why did we move the diagnostic range? Is it because it no longer has significance? I would argue that the standard dietary advice has affected the average oxalate output. We have started to eat more oxalate foods, more regularly, and now we treat see higher oxalate output all the time in patients who are otherwise healthy. This has happened as our standard nutritional advice has pushed us to higher and higher intake as a society. The primary nutritional advice to people has been to: increase plants; eat more “superfoods” like spinach and chard and nuts; and avoid meat or other animal products. This shift to increasing amounts of plants – with a focus on foods that are particularly high in oxalate – has definitely driven up the average oxalate intake, as well as our oxalate output.

As a point to consider, animal products in general have very low to zero oxalate in them. So while it is often recommended to reduce meat intake if you have kidney stones, it may not be the meat in the diet that is to blame. Recent research on the high incidence of kidney stones in oil-rich Gulf States indicate that “[t]he consumption of oxalate in the Gulf is three times higher [than western nations].”

So while people in the Gulf States eat more meat, they also take in more oxalate from many traditional foods, including sesame seeds, pomegranate, pistachios, and spices like turmeric, cumin and cinnamon – and they have more kidney stones. However, authors pointed only to the meat consumption.

Is it really the meat or it is the oxalate? Is bioaccumulation happening more widely than we know? What kinds of impacts could be happening?

Why Oxalate Bioaccumulation Is Important

The challenge with bioaccumulation is the following: we may not see oxalate symptoms directly correlated to oxalate intake. The oxalate can be entering the tissues – and until there is sufficient oxalate load in those tissues, we may not have any distinctive or obvious symptoms. By the time we have distinctive symptoms, we have been eating high oxalate foods for a long time, and so the idea that our “favourite” foods could be making us sick is a particularly unpalatable idea.

However, bioaccumulation can be happening, kicking off processes in the body – most importantly, inflammatory ones – which may contribute to health conditions later. It turns out that oxalate can trigger the inflammasome in our cells, driving inflammation but doing so without a bacterial or infective agent.

Given that inflammation is implicated in many health conditions, the relationship between oxalate and the inflammasome should get our attention.

Oxalate Related Conditions

In recent years, research has shown that a number of health conditions may be associated with poor oxalate management and/or excessive dietary intake. These include breast cancer, arthritis and various lung diseases.

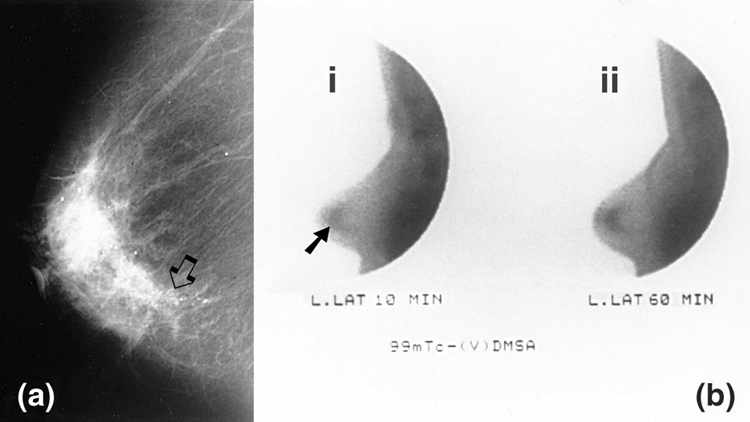

Breast Cancer. If you are eating a very healthy diet, with lots of high oxalate plant foods, what if that is setting you up for illness? While this might seem very surprising, research from 2015 says just that, in the title “Oxalate Induces Breast Cancer”. Note that researchers indicated that microcalcifications can be the early sign of breast cancer – and these calcifications can be oxalate. In fact, oxalate measured higher in breast tumor tissue samples than non-pathological breast tissue.

Another finding of the same research was that oxalate induces proliferation of breast cells. (As part of the same study, researchers showed that oxalate could drive cancer when injected into the fat pad in the breast of a mouse, but not when injected into the mouse’s back.) This alone should be a reason to look at diet and see if a low oxalate diet helps reduce risk!

It may not just be breast cancer; oxalate may also be the driver of benign breast tissue changes as well. Previous research was done on mice; new research has been done on tissue samples from women under treatment for breast tumors (both benign and malignant). In this study, it was possible to see macrophage polarization due to calcium oxalate.

Arthritis. While most research on oxalate as an arthritis driver is limited to primary hyperoxaluria, in this area of study it is clear that oxalate can be affecting joints and contributing to inflammation there. Oxalate crystals have even been found in synovial fluids in association with acute or chronic arthritis.

Some researchers have made the connection from arthritis to secondary hyperoxaluria. In an article from 2013, the authors point out that oxalate is able to gain access to the joints and synovial fluid, where oxalate can cause arthritis that is clinically indistinguishable from other crystal-induced arthropathies.

Airway Inflammation. Oxalate can help drive inflammation – and as a result, can contribute to the worsening of disease when inflammation already exists. When it comes to diseases of the airways, including asthma and COPD, inflammation is the key issue – and oxalate can be involved.

In a study of both asthma and COPD patients (where they had been diagnosed with hyperoxaluria), researchers discovered that hyperoxaluria correlated with an atypical course of bronchial obstruction syndrome. Researchers recommended in their conclusion that treatments that reduce insoluble oxalate may help to prevent both the formation and progression of obstructive pulmonary disease.

Another study showed that restricting or eliminating excess oxalates produced positive decreases in clinical and functional airway obstruction. While the definition of “excess” oxalate is unclear from the abstract, what is clear is that when oxalate was reduced, patients improved. The research abstract reports that patients who had reduced oxalate also reduced their need for broncholytic and anti-inflammatory agents.

Dietary Oxalate and the Explosion of Inflammatory Illness

We have come to think that normal aging just means more pain and problems. But if oxalate is accumulating over years and years – could those disease of aging really be diseases of diet?

What if a number of health issues and disease states are not iatrogenic, but are being driven by inflammation and microcalcification where the oxalate factor is unrecognized? If the medical practitioner dealing with the patient does not realize that oxalate could be a factor, then this health issue will be met with treatments that may be ineffective. Even worse, dietary changes made to try and improve health may be actively and negatively impacting patients.

As a practitioner, I see clients all the time who are dealing with a variety of health conditions, which all benefit from the reduction of oxalate. Perhaps this is something that warrants some independent attention – as most research only looks for oxalate as a factor when hyperoxaluria is already established. I suggest that we might want to examine whether oxalate is affecting us slowly, over time. Perhaps we could reduce or even avoid some of the chronic inflammatory conditions, which are now epidemic in our society.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.