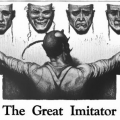

I have been thinking a lot about how we characterize the side effects of drugs. Truth be told, that is a topic that I have pondered on a number of occasions since beginning this website. More often than not, we have no idea about the true breadth and depth of these reactions. We think we do, because assuming some semblance of understanding, even an incomplete one, is what allows us to operate in this space, but when we unpeel the layers of that supposed understanding, it is difficult not to be impressed by how little we actually know.

The manufacturers of these products are required to report adverse reactions and side effects before a drug reaches the market and surveil reactions in the broader population after it reaches the market. From here, regulatory agencies, physicians, researchers, and consumers are expected to trust that we know how these drugs do or do not work. Importantly, we are encouraged by this understanding that any negative reactions experienced will be rare, time-limited, and easily mitigated by other medical products. The possibility that there might be side effects not identified by the original research, that ‘rareness’ is relative, and that ill-effects may not be time-limited or easily corrected is difficult to digest. It throws a wrench in the very foundation of the heavily fortified trust in all things modern medicine.

In reality, it is very difficult to ascertain the scope and depth of potential side effects. This is due in part to the complexity of the interactions between the drug, the human, and the totality of his/her environmental exposures and stressors and in part to the economic underpinnings of these endeavors. If one had to include a broader array of variables in a drug trial, no drug would ever be approved, at least not in a timely or cost-efficient manner. Instead, the initial trials utilize the most healthy of participants, perhaps excluding the disease process in question, and all other variables are excluded, both from the subject pool itself and analytically. Who wants to trial a drug on individuals typical of those who would be taking the drug; on individuals with multiple, often chronic comorbidities, for whom both chronic and acute polypharmacy are the norm and not the exception? No one. That would unfavorably skew the data. Better to have a clean subject pool and limit a priori what might be considered an adverse reaction to those that fall within the typically narrow anaphylactic framework and those that are directly related to the purported mechanisms of action of the drug itself. Addressing potential off-target effects must be eliminated or minimized; ditto for potential interactions between the drug and the unique characteristics of the individual. A clean sample and favorable data are the goal.

To that end, adverse reactions research, analyses, and reporting become a ‘see no evil’ approach. If we do not acknowledge the possibility that these reactions exist, then for all intents and purposes, they do not. This means that only the most severe and ‘on-target’ or anaphylactic reactions may be recognized. Any off-target reactions or side effects are labeled as rare and attributed to extraneous variables, unrelated to the drug but entirely related to some inherent weakness of the human who takes the drug.

If confronted with the prospect of negative reactions or even simply negative data e.g. the drug does not work, it is incumbent upon those involved to utilize analytical tools that highlight the good and hide the bad. Data or participant responses that do not fit the desired narrative must be cleaned or removed, post hoc. When that does not work, it is common to select complex statistical methods that no one but the statisticians themselves understand to obfuscate negative findings. Inasmuch as few physicians and even fewer consumers understand even the most basic statistics, this all but eliminates any questions regarding the veracity of the findings. What is written in the abstract or summary is all that will matter. The lede is buried in the stats so that everyone involved might trust in the medication’s safety, trust in their own knowledge, and move comfortably along with their lives.

I admit, this is a cynical perspective, but it is hard-won. After a decade of publishing HM, researching the analytical methodologies employed by drug companies, of investigating the mechanisms of action of many popular and presumed safe drugs, it is difficult not to be jaded. So flimsy are the safety and efficacy data that one is hard-pressed not to question everything. And so here I am amidst a global pandemic for which multiple products have been rushed to market. Pressure to use these products is intense and I and others are left with the sinking feeling that we do not yet know what we think we know about these products or even what we do not know. What we do know is that the developers and manufacturers of these products have a long and well-established history of shady research practices, of burying negative data, of vilifying anyone who questions these practices, and of financing unquestioning support from politicians, ‘thought leaders’, media, and generally, anyone who might be of use. It is not difficult to recognize those same practices at play here but the desire to be safe quells those concerns for most. We’ll take anything and do anything to end this mess, except perhaps ask why we are here in the first place.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Image credit: PalmaHutabarat

This article was published originally on November 4, 2021.