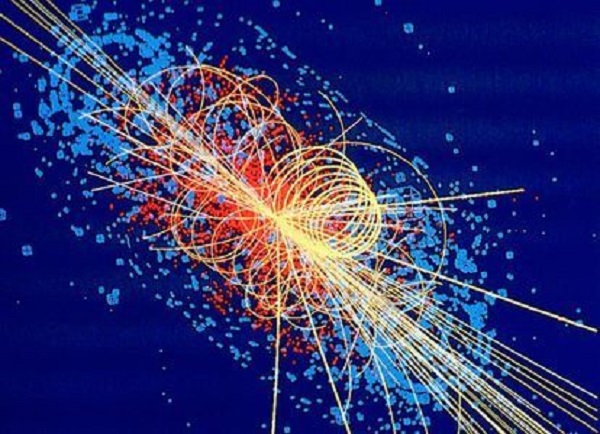

As we begin analyzing the data from our studies and I search for ways to quantify the value of our data, I am repeatedly struck by how the business of modern medicine, especially modern pharmaceutically based medicine, has been conceived of, constructed, and is evaluated on a false and outdated premise of separateness. The notion that a disease is a completely discrete entity, that the disease process is linear and that one medication or set of medications impacts only the specified disease, predominates. This is just not so. Life is complicated, disease is even more complicated, and with the exception of perhaps the outright physical trauma of a limb or the need for immediate decision-making in acute or emergent care, nothing is as simple as the one drug, one organ system perspective from which we measure modern healthcare.

As an example, data from our studies are showing complex clusters of adverse reactions that are multi-system and often evade existing diagnostic categories. The symptoms themselves appear to cluster in ways that are unique and will inevitably lead to a deeper understanding of medication reactions, and hopefully, illness itself. For now, however, they appear to defy the logic of current diagnostic categories. The symptoms never quite fit neatly into a single diagnostic box that defines the disease course or guides a treatment plan.

Instead, the symptoms fall into multiple and sometimes contradicting disease categories, and rather than drill down to an appropriate diagnosis, the individuals in our studies have been assigned a long laundry list of apparently, co-occurring diseases; none, accurately characterizing the scope of their illness. When one disease does not capture the full breadth of symptoms, the trend is to add another. If that doesn’t work and when the interaction between the medications creates more unexplainable symptoms, add yet another diagnosis or three or five. Soon the patient has many active diagnoses, with multiple medications to go with. One has to wonder, how so many individuals can have so many diseases at once. Since, I suspect the laws of probability, and indeed, human physiology are contrary to the current multi-disease trend, it leads me to believe that the western model of defining and treating illness, as anatomically and genetically discrete entities, has reached the limits of utility. A paradigm shift may be in order.

Paradigms, especially in medicine and science, are often guided by forces that determine the limits of what can be known, or more cynically, what are considered acceptable pursuits of knowledge and science versus the flights of fancy of fringe scientists. In this case, I would argue that the forces controlling what can be known are those who profit directly from the current diagnostic system – the pharmaceutical industry. The deeply entrenched conflicts of interest between these corporations, policy makers, regulators, politicians, academic institutions, academic journals, medical societies, patient organizations, media organizations – the very ‘thought leaders’ that determine what is valid and what is not – lends credence to these suspicions.

And by every measure, what is currently valid, are the simplistic and discrete categories, with easily identifiable lists of medications for each, where additional diagnoses equal more medication possibilities or in economic terms more product sales opportunities. Whether the symptoms within these disease categories overlap with each other or even represent a true disease process seems to have little bearing on whether a medication can be fit to match a certain set of symptoms and linked to a diagnostic billing code. The diagnostic billing code becomes at once the arbiter of defined diseases and of what can be known about a particular disease. If there is no billing code, read no product or medication opportunity, the disease doesn’t exist, but if there are multiple, overlapping disease categories, no matter how poorly defined or distant from what the patient may actually be experiencing, there is product opportunity, and therefore the disease, or more likely, the diseases he or she is experiencing, exist. And, if the criteria for defining a particular disease can be relaxed to include more patients and to maximize prescribing opportunities, well then, that is even better.

Consider the most recent recommendation by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology to reduce the risk level for heart attacks necessitating a need for increased prescriptions of statin drugs. The change in guidelines will mean more Americans will be diagnosed with heart disease necessitating prescriptions for the cholesterol lowering drugs, a boon to the drug industry. In a few years, epidemiologists and those who study healthcare trends will report a predictable increase in the number of Americans with heart disease, more money will be poured into preventing heart disease with more medications prescribed and so on. It’s a fantastic business model, control the definition of disease to control the market for products. Will more Americans have heart disease? Not likely, but changing the diagnostic criteria, changing the billing code, to open product markets will give illusion of increasing illness and this benefits the manufacturers of these products.

Unfortunately or fortunately, depending upon which side one is on, lowering the threshold for prescribing opportunities does more than simply increase the number of patients to be given a particular diagnosis, it opens up additional product markets or diagnostic opportunities when the side effects of the primary drug kick in and necessitate treatment. In women, for example, statins increase the risk of Type 2 diabetes. By lowering the criteria for diagnosing heart disease and prescribing statins to more patients, not only will we see an increase in the rates of heart disease in a few years, but because the research tabulating disease rates rely on the diagnostic billing codes, we will also see a corresponding increase in the rate of Type 2 diabetes, most likely created by the increased use of statins. Similarly, because the medication used to treat Type 2 diabetes elicits a corresponding reduction in vitamin B12 levels, which present as a heterogeneous set of neurocognitive symptoms, in a few years, we’ll also see an increased rate of mental health conditions indicated by the growing rates of psychotropic medication prescriptions. And so on.

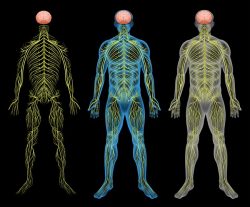

To be both the arbiter of what is known and can be known, to control the definition of disease and the guidelines for prescribing, is a brilliant business model, but one that does nothing to improve human health, further medical discovery or scientific understanding. Indeed, the survival of this model relies entirely on maintaining the facade of anatomical separateness in disease processes and on not recognizing the totality of medication effects across an entire physiological system. This model relies on remaining ignorant of the inter-connectedness of disease processes and by association the possibility of broad based ‘complicated’ medication reactions.

If diseases remain separate entities and medications work only on specified disease targets, then disease categories remain entirely under the purview of those who stand to benefit from prescribing opportunities. Data that link the onset of a disease to the use of a medication or redefine the scope of a disease process and medication target beyond a specified anatomical region can be easily dismissed. And that is where I find myself, having collected data that questions the accuracy of the current model of anatomically discrete, one medication-one target model of disease. Our data question a paradigm. What does one do with that?

We Need Your Help

Hormones Matter needs funding now. Our research funding was cut recently and because of our commitment to independent health research and journalism unbiased by commercial interests we allow minimal advertising on the site. That means all funding must come from you, our readers. Don’t let Hormones Matter die.

Yes, I’d like to support Hormones Matter.

This article was published originally on November 18, 2013.