Over the past several decades, the general consensus of health professionals has been to recommend that all people lower their salt intake. Without the recognition of the effects of lifestyle and dietary choice differences, this avalanche of low salt advice hit the general public and as a direct result many became ill. Differences in individual genetic, lifestyle, and dietary factors have completely been ignored in the broad-brush campaign for lowering salt intake. Today, it is unmistakably obvious that a large segment of the population followed the low salt regimen with disastrous consequences.

The professionals who first introduced and propagated the low salt diets had good intentions. They did not know any better. Now we do know better and there is no excuse for not revising a failed treatment regimen in the face of new countervailing evidence. The process of correction needs to begin on a large scale. My work is part of this very much needed correction.

Why Are We Scared of Salt?

In the 1960’s, scientific studies linked salt consumption to hypertension and obesity. I am not quite sure why it was salt they picked on as “enemy number one.” I suspect the reason was the proliferation of precooked and canned food, all of which were salt preserved. To me, it was not logical that only salt was picked on. There were many other dangerous food items that could have been singled out: sugar, margarine, preservatives, pesticides, etc. The American Heart Association still has some of these salt reduction articles on their website. Even today, when waiting for an appointment at my medical institution, the forever-on TV was showing how to cut salt out of kids’ daily lunch to be “healthy.” Indeed, once something is ingrained in our brains, it is habit forming. Habits are very hard to break, particularly when the medical research relied upon showed that salt is something dangerous that may kill you.

Is Salt or Sugar the Enemy?

The problem is that hypertension and obesity are not and have never ever been caused by salt! They are caused by sugar—I am saving the sugar discussion for my next article.

Why not salt? Consider: human fetuses are floating in salt water and are typically not born with heart attack or hypertension. Our bodies are made of over 7% salt, our brains, heart, and all of our cells use salt to function. Humans have always consumed salt. Do they all have hypertension and heart attacks? No, they don’t. In fact, for some time now, studies have been surfacing suggesting that reduced salt does not eliminate the chances for hypertension and heart attack but may even contribute to the problem.

It is scientifically irresponsible to analyze biological processes in the human body involving salt without accounting for the effects of sugar and sugar substitutes and the amount of water consumed.

Probably not many of you have the handbook “Harrison’s Manual of Medicine” (18th edition McGraw Hill Medical by Longo et al.,) but I do. Page 4

…serum Na+ [sodium] falls by 1.4 mM for every 100-mg.dL increase in glucose, due to glucose-induced H2O efflux from cells.

Let me explain this sentence for you: Sodium is part of salt. Salt is Sodium (Na+) and Chloride (Cl-) where the + and – represent the ionic state in which there is either one extra or one fewer electron (electrons have negative charge) and so the atom is looking for another atom it can attach to and form a bond creating a molecule. According to the medical handbook, Na+ drops if glucose, which is blood sugar, increases. If you eat glucose, it causes “H2O efflux from cells” which means that sugar attracts water to the point that it pulls it out of the cells, thereby emptying the cells of sodium, and thus, the cells are dehydrated.

Sugar causes a very serious problem that can result in hypertension and heart attack. The volume of blood inside the cells reduces by dehydration of the sugar and higher pressure is required to pass the dehydrated blood to traverse the same route and be able to oxygenate organs at the same rate as hydrated blood cells. Think of a water hose when suddenly the pressure drops (unfortunately we cannot replicate reduced water molecule size the same way dehydrated cells become smaller). You instinctively squeeze the hose end to increase pressure so the water can continue to reach to the same distance. You have just given a hypertension to your water hose!

Note that if sodium (page 3 in same book) falls below 135 mmol/L, it is an electrolyte abnormality whose symptoms include “nausea, vomiting, confusion, lethargy, and disorientation”; if Na+ falls below 120 mmol/L it is a life threatening emergency that may cause “seizures, central herniation, coma, or death.” Not having enough salt (sodium) in the body is called hyponatremia and is “primarily a disorder of H2O homeostasis” meaning too much water and not enough salt. In common parlance, this is called water toxicity. Water toxicity can be caused by drinking too much water—e.g. drinking only water.

Interestingly, in the same book under the section of hypertension (page 834-835), the causes of hypertension are listed. Increased salt (or sodium) is not mentioned at all, but glucose intolerance is. However, under treatment, on page 836, it recommends lifestyle modifications that include lowering salt intake. So increased salt did not cause hypertension but lowering will cure it? I do not understand. Do you? Seems the authors of even this highly respected medical reference book could not escape the fallacy of the low salt campaign. Hypertension is clearly listed to be caused by sugar under the causes. So for heaven’s sake, if something is caused by sugar, treat it with removing sugar from our diet and not salt.

Confusion in the Ranks

In recent years a major fight started between the academic groups, not-for-profit organizations, and the government. Test after test shows that earlier hypotheses were all wrong about salt. Not only is added salt not hurting us, reduced salt does. Even the American Heart Association (AHA) and other heart organizations are in complete confusion. Next to the article of “lower your salt for health” are articles saying “that is all wrong and increase your salt.” I find this kind of funny. Here is an article from the AHA suggesting to increase salt. Here is another from the HealthAffairs organization; one from the American Journal of Hypertension, one from the Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, and there are now dozens more proving that indeed, reduced salt is actually bad for you.

How Bad is Reduced Salt on Health?

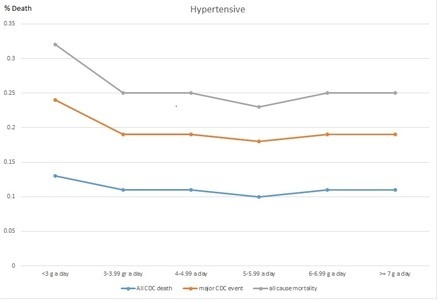

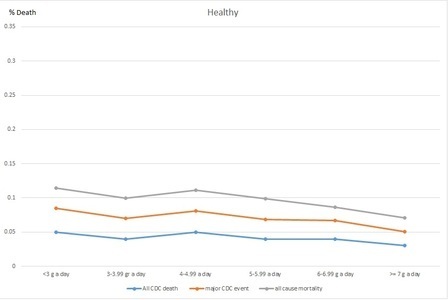

This particular article is my favorite because it shows how bad reduced salt diets really are on the heart. In detail, for a healthy individual reduced salt diet reduces BP by 1% (that means your systolic BP of 120 just dropped to oh my 118.5!!! gasp) and in patients with hypertension it reduced their BP by 3.5% (that is if it is say 160 systolic, which is high, it is reduced by a whopping 5.6 to 154.4! gasp again) but at the same time triglycerides, which contains the accurate measure of the sticky type of bad cholesterol in the LDL increased by 7% in people with hypertension (triglyceride should be less than 149). So if an individual with hypertension and triglyceride levels at 150 went on a low salt diet, that low salt diet would increase their triglycerides by 10.5 to 160.5, which is a significant jump for bad cholesterol. In a healthy individuals, the triglycerides jumped by 2.5%. Armed with such details, do you still believe that salt is bad for you?

Which Would You Rather Eat?

If I handed you 2 teaspoons: one was full of table sugar and the other full of table salt, which would you chose? For taste, we all would choose the sugar. What happens to our salt levels when we eat sugar? Refer back to the Harrison’s Medical Manual I mentioned earlier: eating glucose drops salt in our body because it sucks up all water and dehydrates. Eating a teaspoon of sugar will effectively dehydrate you and put you at risk of hyponatremia. By contrast, what will happen if you chose the teaspoon of salt? You will be thirsty, drink a couple of glasses of water and will feel like you are on top of the world.

My Recommendation

Stop being scared of salt and start being scared of sugar!

Sources

Longo et al., Harrison’s Manual of Medicine; 18th Edition, 2013; McGraw Hill Medicine

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Image by 28366294 from Pixabay.

This article was first published on June 13, 2015.