If the last 80 years of research is any indication, the answer is no, pregnant women are not getting enough thiamine to have healthy and uncomplicated pregnancies. Although the research is sparse, almost every study published since 1940, regardless of country, regardless of food fortification/enrichment programs, and sometimes, in spite of prenatal vitamins, consistently shows deficiency in at least 20% of the women tested and sometimes in as many as 60%. While testing methods, trimester, and diet account for some of the variance, the high degree of congruence amongst these studies demonstrates a glaring misunderstanding of thiamine needs during pregnancy.

Much of this misunderstanding emanates from the original assumptions used to guide research and establish recommended values; assumptions that have since become codified into general practice despite ample contradictory evidence. As the first in a series of papers to build a case for increasing thiamine intake during pregnancy, this article will review the assumptions and research associated with thiamine recommendations for pregnancy.

Origins of the RDA

In the US, the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for thiamine intake during pregnancy is 1.4 mg. In other countries the dietary reference intake (DRI) ranges from 1.3-1.5mg per day. RDA values are set at amounts proposed to prevent deficiency symptoms in approximately 97% of healthy populations and DRI is recent term used to represent all quantitative estimates of nutrient values and is proposed for dietary planning for healthy people. It largely mirrors the RDA.

RDA values evolved from dietary recommendations developed during World War I and the great depression. Originally, recommendations focused on ensuring sufficient protein and caloric intake (3000 kcal) for active service men. In 1939, two women, Hazel Stiebeling and Esther Phipard, expanded those recommendations to include thiamine and riboflavin. Their original estimates suggested 460 international units (IU) or 1.39mg for healthy adults but added the caveat:

The allowance of a margin of 50% above the average minimum for normal maintenance can now be given the clear definition it has always needed. It is an estimate intended to cover individual variations of minimal nutritional need among apparently normal people. . . .

In 1941, the National Research Council (NRC) recommended 516IU/1.55mg for active males. Ultimately, however, 1.2mg was adopted. This was based upon observational governmental surveys, and through committee showing that for healthy 70kg/154lb active males doing muscular work, 1.2mg of thiamine daily was enough to stave off symptoms of beriberi in 97% of this healthy population. While one might realistically consider the dynamic aspect of each of these variables, e.g. the health of the individual, caloric intake, body weight, and/or activity level might change, recommendations for daily intake became fixed and have remained so ever since. These recommendations appeared to disregard Steibeling’s recommendations, the NRC recommendations and contemporaneous findings arguing that while 1.2mg prevented observable manifestations of deficiency, 1-5-2.0mg per day was associated with better overall health.

In planning diets for adults, allowances may well be set two or three times as high as the minimum required to prevent beriberi. This would mean a level of intake of from 1.5 to 2.0 milligrams of thiamin (500 to 666 International Units) for a 70-kilogram adult or about 20 International Units per 100 calorie.

From those reports, it was then assumed that based upon changes in mass and a perceived reduction in activity levels, non-pregnant women required only 1.1mg daily. There was no research, nor has there been any research since to confirm this assumption. From the National Academy of Sciences report published in 1998, the report upon which the NIH currently bases its recommendations:

Studies were not found that directly compare the thiamin[e] requirements for males and females. A small (10 percent) difference in the average thiamin[e] requirements of men and women is assumed on the basis of mean differences in body size and energy utilization.

Based upon additional assumptions of increased energetic demand and mass, the RDA for pregnancy was set to 1.4mg per day. Once again, there was no research to back this up. Even so, these numbers have remained unchanged for 80 years.

Each decade or so, panels in the US and elsewhere, reconvene to assess nutrient intake and re-evaluate nutrient recommendations, and with each report, the same few studies published between 40-80 years ago provide the rational for maintaining the status quo. From the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) report in 2016, a report that reviews work from other agencies worldwide:

The Panel considers that the available data on the relationship between thiamin[e] intake and biomarkers of thiamin[e] status in pregnancy cannot be used for deriving DRVs (dietary recommended values) for thiamin[e] in pregnancy. There are no data on the relationships between thiamin[e] intake and biomarkers of thiamin[e] status in lactating women.

Notably, the most commonly cited study used to justify current values across all agency reports, was conducted in 1979 and involved 7 healthy men.

In general, no matter the country or panel, justification for thiamine requirements in women and during pregnancy involves only a few studies, many of which do not include women, pregnant or otherwise.

Returning to the EFSA for a moment, after discussing all of the early research upon which these values were based, panel members performed an additional comprehensive search for more recently published studies though 2016. A few were mentioned, but the conclusion remained:

The Panel considers that available data on thiamin[e] intake and health outcomes are either limited or inconsistent and cannot be used for deriving DRVs for thiamin[e].

Although there have only been a few studies across the decades that show women require more thiamine to sustain a healthy pregnancy, none have swayed governmental recommendations. Among them, a study conducted at Harvard from 1943 looked at thiamine metabolism and excretion in pregnant versus non-pregnant women. Researchers concluded that pregnant women required 3x the amount of thiamine to reach peak excretion compared to non-pregnant women. Peak excretion studies provided supporting data to justify current recommended values for healthy male adults. They do not consider health variables, but rather the rate at which the largest amount of thiamine is excreted relative to intake. Deficient individuals show no increase in excretion without high doses, usually by injection. The 1979 study of 7 healthy men mentioned above was a peak excretion study.

In accordance with the increased thiamine demand, it is interesting to note that during World War II, reports from a health station in Oslo, Norway, recommended 4mg of thiamine per day for pregnant women and up to 9mg from brewer’s yeast or synthetic thiamine, when available. In doing so, and despite the stressors of war and limited food availability, maternal and infant morbidity and mortality was remarkably low; lower than what one would expect and certainly lower than modern rates of the same complications.

Thiamine Intake and Nutritional Surveys

Based on nutritional surveys conducted in the US and elsewhere, population-wide deficits in thiamine are considered rare. Supporting this conclusion, US nutrition surveys dating back to 1955, show that the average intake for all but the poorest 10% of the population was 1.5mg. These numbers were based upon something called an equivalent nutrition unit, which was calculated using the thiamine intake of 25 year old males. Presumably, it was normalized for everyone else but there are no data as such. From the 1977-78 report onward, values were reported by age and sex. There were still no data for pregnant women, however. The intake for boys and men ranged between 1.4-1.8, while those for girls and women, with exception of girls ages 9-11 (1.3mg), hovered just over a milligram. The numbers were similar for men in the 1987 report, while women increased their intake to around 1.1-1.3mg depending on the age group. In the 1994 reports, women were solidly in the 1.3 range. Reports can be found here.

The most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted between conducted from 2013-2016, found that for non-pregnant women between the ages of 20-30, the average daily dietary intake of thiamine was 1.4 mg/day, suggesting that many women consume sufficient thiamine should they become pregnant. A NHANES survey conducted between 2001-2014 included pregnant women (n=1003) and appears to support this claim. Based upon a single 24-hour recall of food intake, only 10% of respondents were determined to be at risk for deficiency. From foods alone, the average intake was 1.8mg and from foods plus supplements the average was 3.6 mg.

Overall and despite the lack of actual data on thiamine intake during pregnancy, nutritional surveys from 1955 onward suggest that based upon intake alone, thiamine deficiency across the population should be rare. As discussed frequently on this website, and below, it is not.

Deficiency During Pregnancy

Over the years, there have been very few studies published on thiamine during pregnancy in developed countries. Most of the research has been focused on undeveloped regions with food insecurity where thiamine deficiency is endemic. Nevertheless, among the studies that have actually measured thiamine, the results are clear. Thiamine deficiency during pregnancy is quite common. Conservatively and based upon the most recent US studies, ~20% of pregnant women are likely to be deficient at some point during the pregnancy. Across all studies, however, the numbers may go as high as 60%. Below is a listing of studies conducted that include presumed healthy women.

- The effect of pregnancy and puerperium on the thiamine status of women (1943) – US: 50 pregnant women assessed for peak excretion. Results: pregnant women required 3X amount of thiamine than non-pregnant to reach peak excretion. The paper summarized 6 other studies (unavailable) from 1930-1940 that demonstrated reduced to non-existent thiamine excretion in pregnant women, indicating increased need. Animal research was also reviewed and showed 5-10x increased requirement for thiamine, depending upon species, to prevent the abortion or resorption of fetuses, post birth death, or a disorder resembling polyneuritis.

- The influence of nutrition on the course of pregnancy (1950) – Norway: 641 pregnant women, tested via urinary excretion (this is the report mentioned above). Prior to dietary interventions, 44% of the women were to found deficient. This is during WWII, where food shortages were common, nevertheless, by treating the deficiency and maintaining intake at 4-9mg, health complications were very low.

- Vitamin B1 status during pregnancy (1974) – Germany: 533 women. Using the more sensitive erythrocyte transketolase activation (EKTA) test, 25-30% of the pregnant women were found to be thiamine deficient.

- Vitamin profile of 174 mothers and newborns at parturition (1975) – US: 74 mothers not taking oral vitamins and 133 mothers ingesting various vitamin supplements. Even though none had overt signs of deficiency, thiamine deficiency was identified in 53% of the women who were not ingesting supplements and 23% who used supplements.

- Thiamin[e] status during pregnancy (1980) – Ireland: 20 non-pregnant and 60 pregnant women. Here, 30% of non-pregnant women and 28-39% of pregnant mothers (in either the second or third trimesters or postpartum phase of pregnancy) were found to be thiamine deficient.

- Thiamine Deficiency – A Neglected Problem of Infants and Mothers – Possible Relationships to Sudden Infant (1985) – Australia: 13 mothers and infants at term and 52 mother and infants 4-46 weeks post-delivery with adequate daily intake; 50% of mothers were deficient across time points, as were their infants.

- Enzymatic evaluation of thiamin, riboflavin and pyridoxine status of parturient mothers and their newborn infants in a Mediterranean area of Spain (1999) –Spain: Thiamine status of maternal and cord blood from 131 parturient women using the EKTA. Only 37% of the mothers had adequate thiamine; 21% were marginally deficient and 41% were severely deficient. Of note, thiamine and pyridoxine deficiencies were highly correlated in the women. For the infants, using measures of vitamins from cord blood at term, researchers found that 33% were deficient in thiamine. The Australian study (1985) cited above, found a high risk of SIDS and a high familial incidence of SIDS in low thiamine infants.

- Thiamin[e] status of gravidas treated for gestational diabetes mellitus compared to their neonates at parturition (2000) – US: Of the 77 women with gestational diabetes tested, 19% of the women had low thiamine. As with the previous studies, neonates born to women with low thiamine also had low thiamine.

- Thiamin[e] status during the third trimester of pregnancy and its influence on thiamin concentrations in transition and mature breast milk (2004) – Spain: 51 women. Using an ETKA test, 59% of the women were moderately deficient (EKTA >1.20) and 38% were severely deficient (EKTA >1.25).

- Dysfunctional protection against advanced glycation due to thiamine metabolism abnormalities in gestational diabetes (2016) – Czech Republic 177 pregnant women (99 GDM, 78 healthy controls). On the surface, researchers found low rate of deficiency among both groups, 5 and 6% respectively (EKTAC> 1.15) but when the data were adjusted for body mass index (BMI), women with higher BMI and GDM had increased thiamine delivery to the cells without the expected increase in enzyme activity suggesting problems with thiamine metabolism/functional thiamine deficiency. This will be discussed more in subsequent papers.

There were a few studies during this time period that were unable to detect deficiency. These included:

- Thiamine and riboflavin intakes and excretions during pregnancy (1950) – US: 15* women on a regular diet; 1.3mg oral thiamine was given for 7 days and urinary excretion measured. Excretion paralleled intake (high intake, more excreted), except in women consuming less that <1mg of thiamine daily, where excretion increased 2-3X over non-pregnant women. This was in contrast to the 1943 cited above that found 2-3X increase globally but methodology, dosage, and delivery route (injected versus oral), were also different. *Five women were excluded due to excessively low caloric intake, so the sample size was technically only 10 despite claim. Moreover, low caloric intake could be considered either cause or consequence of low thiamine.

- Longitudinal vitamin and homocysteine levels in normal pregnancy (2001) – Netherlands: cohort of 225 women tracked before conception, during pregnancy, and postpartum from 1987-90. Data displayed via scatterplot with no statistics provided and no discussion of deficiency. While roughly 30-40 data points fall below deficiency values across all time points, it is impossible to know how many within-subject measurements those data represent.

Conclusion

Despite a longstanding belief that pregnant women require only 1.4mg thiamine per day, the research confirming this number is severely lacking. Similarly, the oft repeated assertions that thiamine deficiency is rare during pregnancy is also in conflict with the data. Although the research is sparse, the conclusions are clear. Not only is it likely that far more women are deficient than is recognized by population-based data, but the very nature of the RDA assumptions may be called into question. While one can accommodate potential errors and misunderstandings about nutrient intake that might have swayed recommendations in the early days of vitamin research, the underlying assumptions that women are simply small men and that changes of pregnancy can be represented solely by a change in mass, seems a far stretch of the imagination, especially by today’s standards. And yet, that is the state of vitamin research.

Since medical decisions, then as now, are made based upon these assumptions, it behooves us to challenge them. What if these assumptions are as wrong as they appear? What if the research on deficiency during pregnancy, as sparse as it is, is actually correct? And what if we are missing an opportunity to help women have healthier, complication free pregnancies simply by increasing the intake of this and other nutrients? Would not it be worth it to reassess what we thought we knew about pregnancy and nutrition through the lens of what we now know about bioenergetics and metabolism?

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Photo by freestocks on Unsplash.

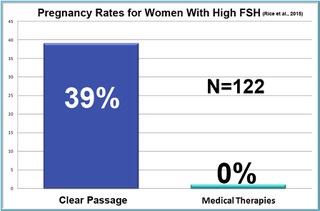

One of the biggest surprises in the ten-year study was in women who were diagnosed hormonally infertile due to high FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone). As a woman approaches menopause, her ovaries demand more and more FSH to stimulate egg growth in older follicles. Measured early in the menstrual cycle, most physicians feel a woman’s FSH levels should be at or below 10 mIU/mL. When a woman’s FSH is above 10, she is considered unlikely to conceive. At FSH of 25, the woman is generally considered to be menopausal.

One of the biggest surprises in the ten-year study was in women who were diagnosed hormonally infertile due to high FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone). As a woman approaches menopause, her ovaries demand more and more FSH to stimulate egg growth in older follicles. Measured early in the menstrual cycle, most physicians feel a woman’s FSH levels should be at or below 10 mIU/mL. When a woman’s FSH is above 10, she is considered unlikely to conceive. At FSH of 25, the woman is generally considered to be menopausal.