Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Diet Variable

Nearly one in eight children (12%) are reported to have had three or more negative life experiences associated with levels of stress that can harm their health and development. In 2011, nearly 60% of children age 17 and younger were exposed to violence within the year, either directly as victims or indirectly as witnesses. Twenty-one per cent of children in the United States suffer from mild behavioral health problems and an additional 11% struggle to overcome significant behavioral health, according to the Adverse Childhood Experiences study. This estimate translates into a total of 4 million youth who suffer from major mental illness (US Department of Health and Human Services 1999, 123-124). An estimated 26% of Americans aged 18 and older (about one in four or over 57 million adults) suffer from a diagnosable mental disorder in a given year.

As if this were not enough, the Children’s Crisis Treatment Center in Philadelphia indicated that “in 2011, 29% of students in grades 9 through 12 reported feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two or more weeks in a row in a year. Up to 70% of children and teenagers in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health disorder and up to 44% of high school students suffering from behavioral health issues drop out of school”. If these statistics are accurate, they are deplorable.

Malnutrition as a Major Cause of Brain Disease

With these huge numbers involved, of many potentially causative issues, there is considerable evidence that bad nutrition may dominate them. It is interesting that, many years ago, a Probation Officer in Cuyahoga Falls in Ohio persuaded a judge to hand over to her care all the juvenile criminals that stood trial in his court. She regulated their diet and supervised it. The recidivism (habitual lapsing back into crime) dropped to almost zero. Unfortunately, good nutrition is commonly overcome by hedonism (love of pleasure) and is usually governed by the sweet taste. There are two aspects to this. Sugar in all its different forms precipitates thiamine deficiency and the signal from the tongue to the brain is responsible for its addictive qualities. There is little doubt that thiamine deficiency is heavily responsible for much of the mental disease that is so commonly represented in our culture. It is especially damaging to the lower part of the brain that governs our emotional responses and our ability to adapt to a hostile environment. Because thiamine deficiency produces an effect similar to that of oxygen deficiency (hypoxia) it has been seen as a cause of pseudo-hypoxia (false hypoxia). Either true or false hypoxia is interpreted by the brain as a potentially dangerous threat to the organism.

Some years ago I had the opportunity to visit the Philadelphia Crisis Treatment Center that then existed under another name. I learned of a neurosurgeon who had been deeply involved with its original inception. He had suggested that seizures (epilepsy) were caused by a deficiency of oxygen (hypoxia) in the brain, perhaps explaining the usual resistance of juvenile seizures to drug treatment. Although the statistics above did not specify the nature of “major mental illness” in 4 million youths, I pondered over the years whether hypoxia or any part of its equivalent mechanisms (pseudo-hypoxia) could be the underlying cause common to brain disease in a variety of different expressions, including even epilepsy in some cases.

After my visit to Philadelphia, I had an opportunity to test the neurosurgeon’s suggestion by treating a 12-year-old boy in “status epilepticus” after his current medication had been suddenly withdrawn. I gave him an intravenous injection of thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide (TTFD), a synthetic derivative of thiamine) and this quickly stopped the continuous seizuring. I then started TTFD by oral administration but it was discontinued by a neurologist who saw the incident as “spontaneous remission and nothing to do with vitamin therapy”. Unfortunately, I did not have any data to be able to publish the case. Status epilepticus is the name given to a situation where the seizuring is continuous and often very difficult to stop. It usually occurs when a medication is suddenly withdrawn. Many years later, I discovered that thiamine deficiency could produce the same symptoms as brain hypoxia, thus giving rise to describing this deficiency as pseudo-hypoxia (false hypoxia). I had evidently treated the SE by relieving the pseudo-hypoxia in the brain cells responsible for this patient’s potentially fatal illness.

Maternal Diet and Neurological Development

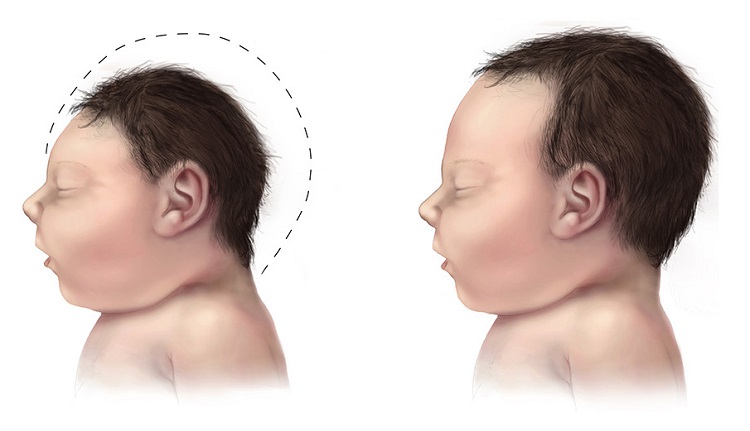

There is growing concern about the long-term neurologic effects of prenatal exposure to maternal overweight and obesity, a result of malnutrition. The causes of epilepsy are poorly understood and in more than 60% of the patients no definite cause can be determined. Authors from the well-known Karolinska Institute showed that there was indeed a relationship between obesity in pregnancy and the risk of epilepsy in the offspring. Although the mechanism is not articulated, micronutrient deficiency may be culpable. Increasingly, it has become clear that a person’s weight does not correspond to their nutritional status. Indeed, in many cases, obesity is associated with a state malnutrition; a malnutrition we call high calorie malnutrition.

Clinical thiamine deficiency is defined by both consistent clinical symptoms and either a low whole-blood thiamine concentration, significant improvement, or resolution of consistent clinical symptoms after receiving thiamine supplementation. Of 400 obese patients, 66 (16.5%) were shown to have clinical thiamine deficiency. Their symptoms included gastrointestinal, cardiac, peripheral neurologic and neuropsychiatric manifestations, the characteristic symptoms of beriberi. Hypoxia threatens brain function during the entire life span, starting from early fetal age up to senescence. A relatively common condition in newborns is lack of adequate oxygen supply to the brain and is known as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. This has been shown to correlate with multiple organ dysfunction and must surely be a severe legacy in the affected child.

The outstanding question then is whether poor diet, perhaps coupled with genetic risk in some cases, could be a substantial causative factor in widespread brain illness. Dr. Marrs and I have published considerable evidence that high calorie malnutrition, by inducing thiamine deficiency, is widespread throughout America and is responsible for a variety of brain related symptoms. With an excess of simple carbohydrate calories, the action of thiamine in burning those calories is overwhelmed. Thiamine might well be in a sufficient concentration for a healthy diet but insufficient for an excess of empty calories. It is the proper calorie/thiamine ratio that results in oxidative efficiency. Unfortunately, the many symptoms produced by thiamine deficiency in the brain are not recognized by the vast majority of physicians for what they represent. If thiamine deficiency is even suspected, they find a “normal” blood level of thiamine that is the usual result in moderate deficiency. The symptoms are falsely attributed to “a more acceptable diagnosis”. No appropriate laboratory tests are usually performed and in many cases the patient is diagnosed with psychosomatic disease, without even considering a necessary underlying mechanism.

High Calorie Malnutrition and Emotional Lability

This kind of malnutrition can severely affect emotional reactions, resulting in a variety of manifestations that include persistent anxiety, depression and bizarre behavior. We have even suggested that poor emotional control can lead to expressions of violence that hitherto have had no explanation for their almost daily occurrence in America. Poverty, poor education, environmental pollution and hedonism are all components that are predictable causative agents. When energy production in the brain is compromised by inefficient use of oxygen (oxidation), the affected person is unable to muster an adequate biological response in the process of adapting to virtually any form of stress. The affected patient is also wide open to succumbing from infection by any microorganism. Brain function becomes abnormal from lack of energy drive.

This may explain the breakdown in health in the children exposed to the stress of active (physical) or passive (mental) violence referred to at the beginning of this post. The well-known saying that “we are what we eat” should be broadened to “we behave according to what we eat”. So many books have advocated the principles of healthy nutrition, without producing much overall health improvement. There is a fairly consistent refusal to “give up” sugar, mainly because its ubiquitous consumption makes it hard to understand its inherent danger to complete health and its addictive properties. Perhaps a more logical attitude might be required to the use of nutritional supplements. The pharmaceutical industry has most people attuned to consumption of pills, so that a transfer of principle would probably be easy. However, it also demands a realization that disease can be reduced to an understanding of energy deficiency as the root cause.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.

This article was published originally on January 13, 2020.