The purpose of preventive mammography screening is to diagnose breast cancers that would result in death at an early stage, thereby decreasing the incidence of late stage breast cancer and overall breast cancer mortality.

A number of reviews and studies have been published over the past several years to determine the effects of mammography screening in achieving these goals. They reveal that mammography screening provides little to no benefit in terms of reducing breast cancer mortality, and yields significant risks and harm to women who receive false positive results and especially to those who are overdiagnosed and overtreated. The risk of overdiagnosis of cancers that would never have been a threat to or even discovered by women in their lifetime includes future treatment-induced cancers.

Statistical percentages such as a 20% or 30% reduction in mortality, ordinarily referenced in reports promoting mammograms, mislead women into thinking that a large number of lives are being saved. However, by looking at the actual number of lives saved by preventive screening in light of the total population screened and the actual number of women harmed by false positives and overdiagnosis we have a truer picture of the effects of mammography screening on breast cancer mortality. Real numbers show that the actual risk to women of dying from breast cancer is far less than women are led to believe while the risk of overdiagnosis, rarely mentioned, is far greater than they would expect. Studies showing a mortality reduction with mammography screening often manipulate statistics to misrepresent the perceived benefits.

The perception that mammography is of great benefit is also influenced in part by the promotion of screening as a life saver and by overdiagnosed women believing their lives were saved.

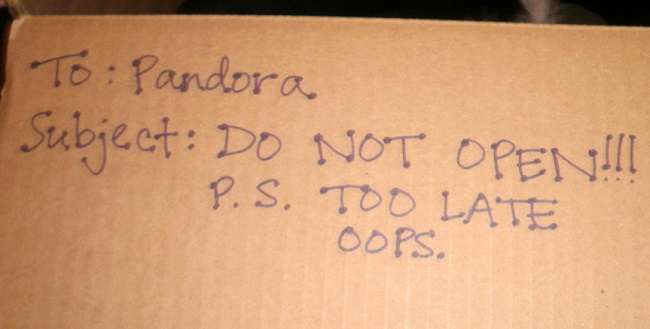

Despite evidence to the contrary, medical and charity organizations support continued mammography screening of women. Women are not made aware of the real evidence against screening. This is in part because of vested interests and in part because of consumer demand for preventive testing based on the even miniscule possibility that it may save their life. However, if women were aware that the possible harm is far more significant than any possible benefit, they would probably opt out of preventive mammography screening.

The breast cancer industry benefits from women’s lack of knowledge. It is not in their best interest to tell women the truth.

Marketing Mammography by Disregarding Data

Preventive mammography screening is supposed to save lives by detecting and treating cancers at an early stage, before they become clinically evident. This is supposed to reduce the numbers of late stage breast cancers and the overall mortality from breast cancer.

This is what every woman who goes for preventive mammography screening believes and what organizations like the American Cancer Society promote and charities such as the Susan G. Komen Foundation will have you believe with those ubiquitous pink ribbons and their “Run for the Cure”.

While you continue to wait for them to finally discover a cure, be aware of the following: despite the assertion that “mammograms save lives” the truth is that millions of women are being misled into undergoing a screening that has been shown over the years to do more harm than good in multiple ways.

If the end result was a really significant reduction in breast cancer mortality we might concede that some of those harms are worth the risk. Unfortunately, too many studies have shown that although more early stage cancers are being detected there is no reduction in the overall mortality from breast cancer and that screening significantly harms more women than it helps. The dangers of screening include many false positives with additional diagnostic testing and, more critically, a high rate of overdiagnosis — the detection of cancers that would never have been a threat to or even discovered by women in their lifetime. Overdiagnosed cancers lead to overtreatment with surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy that needlessly put women at risk of future treatment-induced cancers. Preventive breast cancer mammography screening has really been a colossal failure and the wool continues to be pulled over women’s eyes.

What the Research Really Shows

Consider the following reviews and studies (published between 2011- 2015):

- In a retrospective trend analysis on mammography screening, researchers Philippe Autier, Mathieu Boniol, Anna Gavin, and Lars J. Vatten compared 3 pairs of neighboring European countries having similar population structure, socioeconomic circumstances, quality of healthcare services, and access to treatment where mammography screening was implemented many years apart in order to determine the effect on mortality that such screening had on early detection of breast cancer. “Our study”, they concluded, “adds further population data to the evidence of studies that have used various designs and found that mammography screening by itself has little detectable impact on mortality due to breast cancer.”

- Drs. Archie Bleyer and H. Gilbert Welch discussed their 30 year review of United States data related to mammography screening of women 40 years of age or older. They found that while screening mammography has been associated with a doubling in the number of early stage cancers detected, it has only resulted in a decrease of 8 cases of late stage cancer per 100,000 women. This disparity is attributed to an estimated overdiagnosis (and overtreatment) in the past 30 years of 1,300,000 women or an overtreatment rate of 31% of all diagnosed breast cancers.

- The Swiss Medical Board, an independent health technology assessment initiative, performed a comprehensive review of mammography screening, noting the controversy over the previous 10-15 years regarding mammography’s benefits. Reviewing mammography screening from the first trials 50 years ago in New York City to the most recent led to the determination that it’s possible that of 1,000 women screened, one death attributable to breast cancer might be prevented although there was no evidence showing that overall mortality was affected. However, the prevalence of false positive tests and overdiagnosis, they concluded, causes women more harm than good. For every breast cancer prevented over a course of ten years of screening, beginning at age 50, between 490 and 670 women will have a false positive diagnosis and repeat examination; between 70 and 100 women will have an unnecessary biopsy; and between 3 and 14 women will be overdiagnosed.

- The Nordic Cochrane Report, an independent reviewer of scientific studies, reviewed 7 eligible studies comparing women ages 39 – 74 who were and were not screened using mammography. The authors, Peter C. Gøtzsche and Karsten Juhl Jørgensen, determined that breast cancer screening reduces mortality by approximately 15% and that overdiagnosis and overtreatment is at 30%. Realistically, this means that for every 2000 women invited for screening over the course of 10 years, one woman will have avoided dying of breast cancer while 10 healthy women will have been overdiagnosed and overtreated. In addition, over 200 women will have a false positive diagnosis requiring additional screening.

- The 25 year follow-up for the Canadian National Breast Screening Study, by Anthony B Miller, et al., which compared screened and unscreened women ages 40 – 59 for breast cancer mortality, found no reduction in mortality as a result of the screening. They determined that there was an overdiagnosis of breast cancer of 22% among women with screen detected invasive cancers. Screening 44,925 women resulted in an overdiagnosis of 106 women or, in other words, for every 424 women screened, one woman was overdiagnosed.

Statistical Shenanigans in Mammography Numbers

The article that I like most however (a touch of sarcasm here) is this one that headlines:

National screening programme has markedly reduced breast cancer mortality

Read only the headline or just the first two paragraphs and you will have confirmed that mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality between 20 – 30% in the women who undergo testing.

Continue to the third paragraph and you will find that the study actually corroborates all the other ones listed above – that very few lives are saved by preventive mammography screening and that a far greater number of women are overdiagnosed and overtreated. It reads:

“The evaluation examined a number of sides to the national screening programme and determined among other things that the probability of being overdiagnosed by screening is five times higher than the probability of avoiding death by breast cancer. Overdiagnosis in this context means that without being screened, the women would never have noticed, been aware of or died from the disease. Under the Norwegian Breast Cancer Screening Programme, all women aged 50 to 69 are invited for mammography screening every two years. Under the programme, for every 10,000 women invited to 10 rounds of screening, roughly 377 cases of tumours or pre-malignant breast lesions will be detected. From this group, roughly 27 women will avoid death from breast cancer as a result of early diagnosis and treatment. However, roughly 142 of them will be overdiagnosed with a disease that will turn out to be harmless.”

It should also be noted that the prevalence and harms of false positive results, although not discussed in the article, are considered in the evaluation report. They are also not insignificant.

Although the other reports cited above show even more harm and fewer lives saved, we can clearly see from the intentionally misleading Norwegian report, just how inconsequential mammography screening is in reducing breast cancer mortality.

Declaring a reduced mortality rate of 20-30% due to screening without providing actual numbers is highly deceptive. The key isn’t the percentage but the actual numbers upon which those percentages are based. If we found that 5,000 of these 10,000 screened women were diagnosed with a breast cancer that would have metastasized and 25% are saved from death by early screening, then 1250 women would have been helped. However, given the actual figure of 27 women saved, a 20 – 30% reduction of mortality takes on a very different meaning.

In reality, the headlined “marked mortality reduction” figures were actually calculated based on the assumption that without screening either 135 women (20% reduction) or 90 women (30% reduction) will have been assumed to die of breast cancer. In other words, among 10,000 women not screened, from 9/10 of one percent to 1.35% of the women would likely die from breast cancer. This also means that between 63 -108 women will die of breast cancer regardless of having been screened. (It has been found that breast cancers which metastasize are quite aggressive and often become palpable within a year after screenings that yielded negative results. False negative results can also be to blame.)

The 377 women diagnosed with tumors or pre-malignant breast lesions out of the 10,000 women screened represent almost 3.8% of the screened population. The 27 treated women who avoided death by screening represent not quite 3/10 of one percent (.0027) of the 10,000 screened women. The 142 women needlessly diagnosed and treated represent 1.4% of the 10,000 women screened.

Overdiagnosis Feeds Misperception and Profits

When looking at the actual number of women involved, the 20-30% mortality reduction doesn’t sound so wonderful anymore – but then neither does the risk of breast cancer seem as scary.

Nevertheless, this estimate of breast cancer mortality with or without screening is far less than most women believe population and personal risk to be. According to the Swiss Study cited above women believe that for every thousand women screened 80 will die from breast cancer while for every thousand women not screened 160 will die from breast cancer. The real effect of screening, they found, is that for every thousand women screened 4 will die from breast cancer and for every thousand women not screened 5 will die from breast cancer.

Why the great disparity between women’s real and perceived risk of dying from breast cancer?

As expressed in the Norwegian study’s evaluation report, just the fact of the screening programs alone increase women’s perception of the risk of and mortality from breast cancer.

More importantly, however:

“Overdiagnosis creates a powerful cycle of positive feedback for more overdiagnosis because an ever increasing proportion of the population knows someone—a friend, a family member, an acquaintance, or a celebrity—who “owes their life” to early cancer detection. Some have labeled this the popularity paradox of screening: The more overdiagnosis screening causes, the more people who feel they owe it their life and the more popular screening becomes. The problem is compounded by messages (in the media and elsewhere) about the dramatic improvements in survival statistics, which may not reflect reduced mortality, but instead be an artifact of overdiagnosis—diagnosing a lot of … women with cancer who were not destined to die from the disease.[1]”

This all raises the question: Why the continued emphasis on screening when we have so many studies that all show little benefit to mammograms and in reality significant harms?

Science writer John Horgan in his article Consumers Must Stop Insisting on Mammograms and Other Ineffective Cancer Tests blames the continued use of mammography screening on financial benefits and on consumer demand for testing. About the profit motive he points to an editorial about mammography screening in the British Medical Journal:

“The BMJ editorial urges health-care providers to reconsider priorities and recommendations for mammography screening and other medical interventions.”

“The editorial adds, ‘This is not an easy task, because governments, research funders, scientists, and medical practitioners may have vested interests in continuing activities that are well established’.”

About the consumer demand for testing he says:

“… ultimately, the responsibility for ending the testing epidemic comes down to consumers, who too often submit to — and even demand — tests that have negligible value. Our fear of cancer, in particular, seems to make us irrational. When faced with evidence that PSA tests [yes, prostate cancer as well as thyroid and lung cancer are also overdiagnosed – CL] and mammograms save very few lives, especially considering their risks and costs, many people say, in effect, ‘I don’t care. I don’t want to be that one person in a million who dies of cancer because I didn’t get tested.’ Until this attitude changes, the medical-testing epidemic won’t end.”

Perhaps if they knew that testing may cause them to be one of those several thousand who increase their risk of dying from testing, they would reconsider.

I still remember the commercials made by Sy Syms of discount designer clothing store fame. He would always say: “An educated consumer is our best customer.” For the medical industry, it seems, their best customers are the ones they keep in the dark.

Additional Resources and Reading

Cancer Active

Breast Cancer Action

Screening For Breast Cancer with Mammography

Exposed

The Mammogram Myth: The Independent Investigation Of Mammography The Medical Profession Doesn’t Want You To Know About

Overkill: An avalanche of unnecessary medical care is harming patients physically and financially. What can we do about it?

This article was published originally on Hormones Matter in June 2015.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

[1] http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/102/9/605.full

This article was published originally on June 20, 2017.